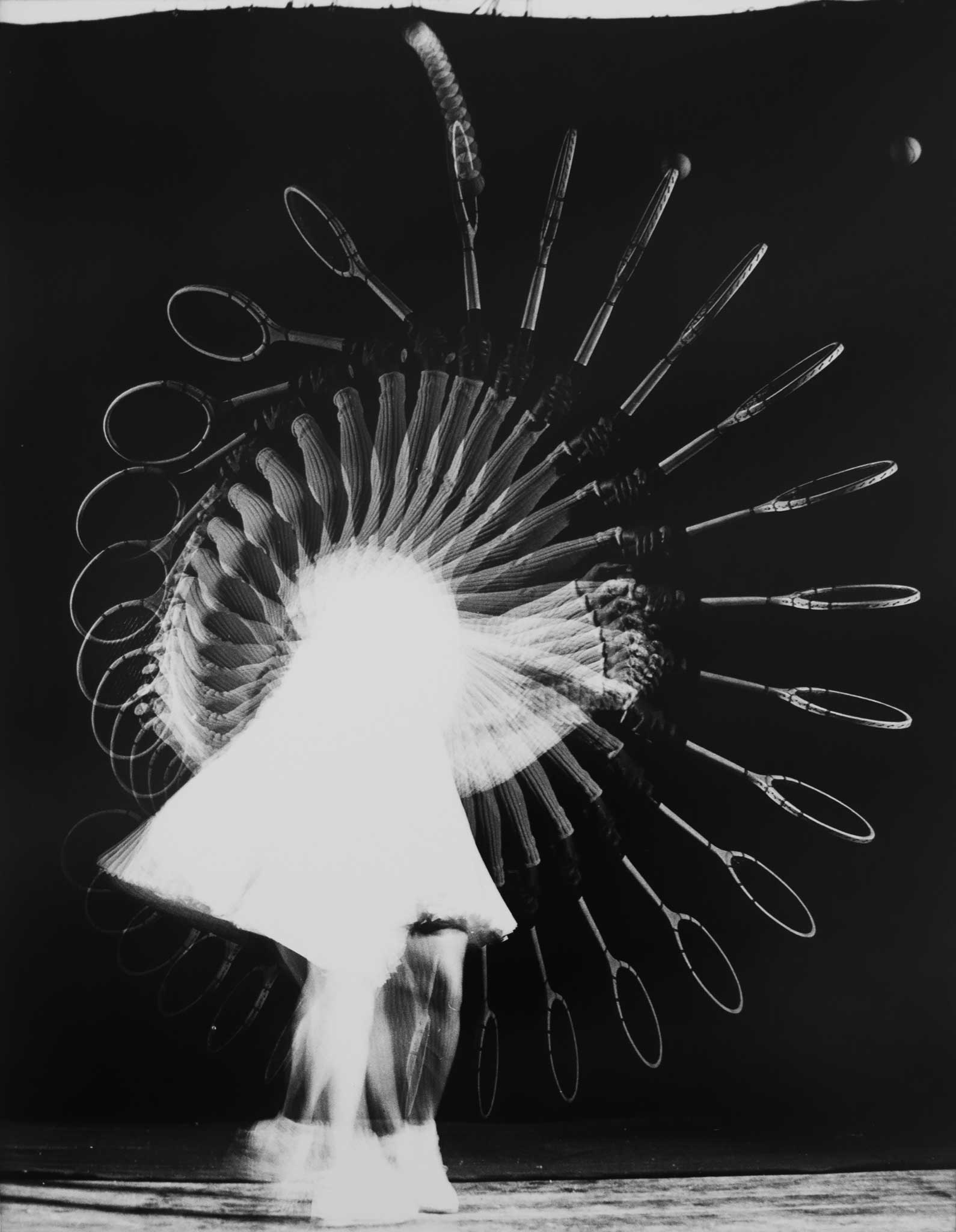

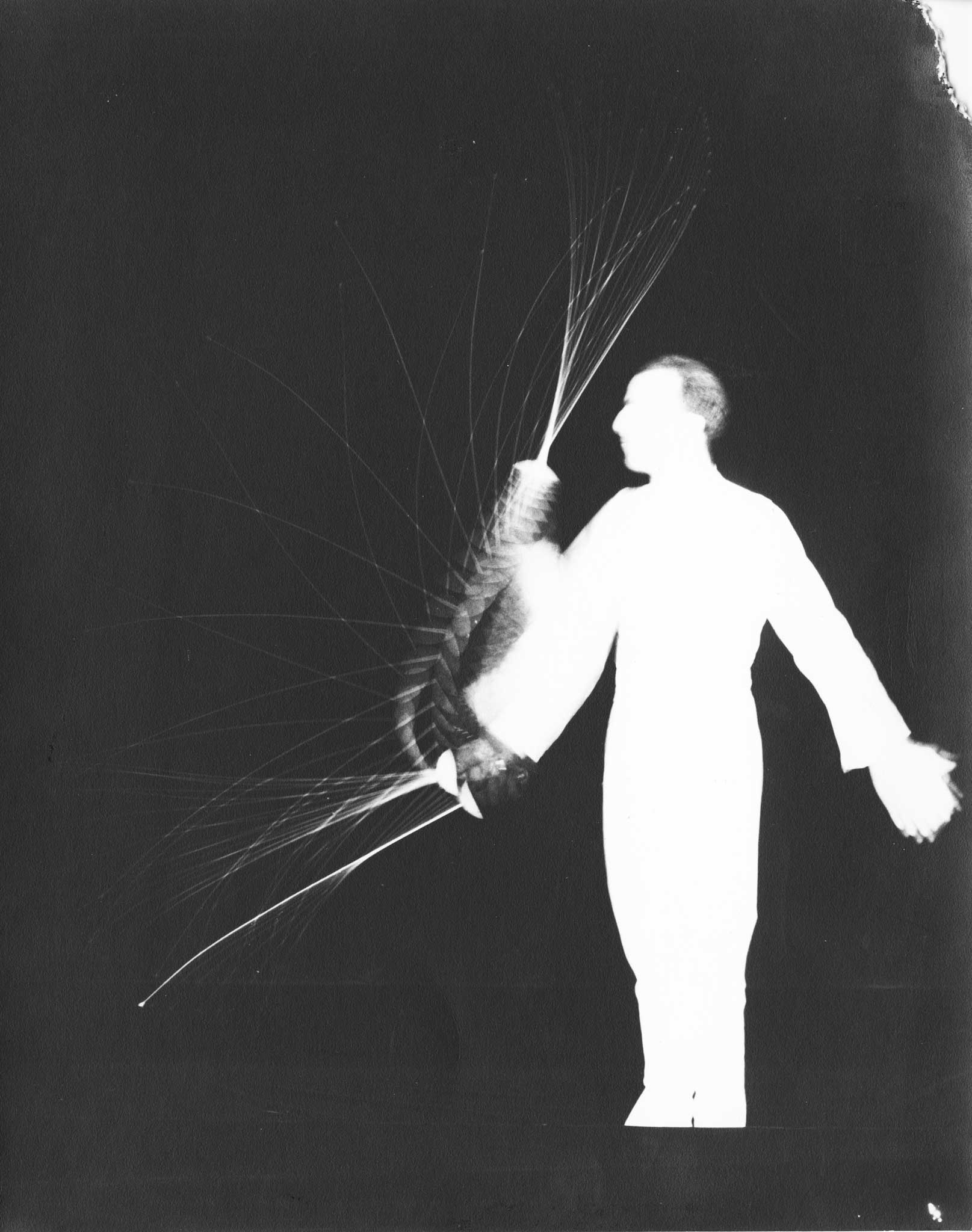

Portfolio: Nebraskan-born engineer Dr Harold Edgerton photographed motion that was too fast to be captured with traditional methods

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Dr Harold Edgerton led the sort of life that lends itself to a Hollywood biopic. During his illustrious career the MIT professor, who died in 1990 at the age of 86, made advances in night aerial photography that was used during the Second World War, photographed nuclear testing in the 1950s and 1960s, and used radar to help illuminate the ocean floors for Jacques Cousteau.

But it is probably the electronic stroboscope for which he is most remembered. This pioneering work allowed the Nebraskan-born engineer to photograph the previously unseen: motion that was too fast to be captured with traditional photography.

Strobe-light equipment that could flash up to 120 times a second meant Edgerton was able to present shots of balloons at various stages of bursting, or an apple exploding as a bullet tore through it. Other famous works captured sports people in action, and drops of milk coming into contact with a body of liquid.

A new exhibition of his work will include previously unseen images from Edgerton's private collection, from the 1930s through to the 1950s, as well as extracts from his notebooks.

"He was able to show the world in slow motion," says gallerist Michael Hoppen. "He wanted to reveal these minute moments in all their beauty and all their complexity."

Although Edgerton famously said, "Don't make me out to be an artist. I am an engineer. I am after the facts, only the facts", it is hard to look at his spectacular images without having an aesthetic appreciation for them. After all, he is responsible for making "frozen movement" part of our visual culture.

"Photography is bound by science," observes Hoppen. "Science, art and technology is more perfectly formed within photography than any other art form; you can't escape that."

Planned or not, Hoppen insists that it was Edgerton's inquisitive mind that led him to create images of such stark beauty.

"The desire for us to investigate the minutiae of life, or the expanse of space, is all about that search and that hunger for the truth."

'Dr Harold Edgerton: Abstractions' is at the Michael Hoppen Gallery, London SW3, 6 June to 2 August, michaelhoppengallery.com

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments