Pauline Boty: The marginalised artist of British Pop Art is enjoying a revival

Pauline Boty was a darling of the Swinging Sixties. Now, nearly 50 years after her tragically young death, her extraordinarily vibrant work is enjoying a revival. It’s long overdue

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.In the flurry of recent exhibitions of British Pop Art, one name keeps recurring with works of astonishing freshness and warmth. It is Pauline Boty, the only woman among the founding members of the movement, who died tragically young, aged only 28, in 1966.

Ignored for decades after her death – it was nearly 30 years before her first picture was shown – a proper retrospective has had to wait until this year with a show which originated in Wolverhampton and has now opened in the Pallant Gallery in Chichester.

Looking at her pictures today, it is simply incredible that it has taken so long. Her gender no doubt partly accounts for her decades of obscurity, as for the revival of interest now. Pop Art started out as a very male-dominated movement and it continued as a chauvinistic and at times crudely objectifying culture. Boty, for all that she was trained at the Royal College of Art alongside Peter Blake, Derek Boshier, Patrick Caulfield and David Hockney, was always slightly the odd one out, too female in her passions for the men and too feminine in her imagery for her own sex. If women were to be the equal of men, then they had to be as serious as men. Glorying in the sexiness of male pop idols and revelling in the imagery of advertising was doing the cause no good at all.

Times have changed and it is now possible to look on Pauline Boty less as a fellow traveller to the men who led the Pop movement and more as a woman artist who asserted her own sex and sexuality before her time. It’s also possible to see just what a good artist she was in painterly terms. Trained as a stained glass artist, her feel for composition and colour is extraordinarily vibrant, while her ultra-realist faces and figures taken from photographs looks forward to the photorealism of a generation later.

You can’t take gender out of her equation. She certainly didn’t. But it is also possible to exaggerate it. Her grandmother was an Iranian married to a Belgian sea captain and trader who died shortly after being taken by pirates. Her father, after being shipped around friends and family, settled in south London to become an accountant and an Englishman more English than the English.

With three brothers, including twins, she certainly had to assert herself to make her presence felt at home. Her father expected her to leave school and marry. She declined, going first to Wimbledon School of Art and then the Royal Academy, applying for the stained-glass course as that was the one she was more likely to get into. Whether this was because she was a mere “slip of a girl” who wouldn’t get into the painting course, as later recalled, may or may not have been true. She undoubtedly faced male prejudice, not least because she was blonde and good looking. But her revolt was as much against the claustrophobia of a suburban conventional upbringing as the constraints of the corset.

Half the pop stars, male and female, who made the Sixties came from similar backgrounds, letting down their hair and strumming their guitars as they enjoyed the first fruits of a generation new to higher education and popular cultural influences from across the Atlantic. One of the pleasures of the exhibition at Pallant House, is to see how quickly she moved in her student work from imitating the works of Cézanne, Bonnard and Chagall that she had seen in Paris to the world of glamour, advertising and pop music she was enjoying as a student.

It was collage, championed by Eduardo Paolozzi at the time, which freed her. As a stained-glass student she readily took to the combinations of block colour and outlined figure which that discipline promoted. ‘Untitled (Girl on the Beach)’ from her first years at the RCA is a conventional, although striking, picture in the manner of Picasso. Within a year, she was making sophisticated collages, adding actual lace as the frame for a Chagall-like landscape of deep purple and sweepingly brushed green in Untitled (Landscape with Lace) and inserting what was to become her trademark images of the manicured hand and roses representing female sexuality in a Surrealist collage in Untitled (Pears Inventor) from 1959.

Bliss was it to be alive in the late Fifties when the Sixties were born and Boty, good-looking and ever energetic, joined in the fun, acting in films and revues, stripping off for the popular press, being photographed by David Bailey for ‘Vogue’, appearing as one of the boys in Ken Russell’s seminal film, Pop Goes the Easel and helping found an action group against bad architecture. Perhaps it was all this glamour and performance which has been held against her. Proper artists aren’t supposed to appear in Tit-Bits and Men Only.

The wonderful thing about Pauline Boty, however, was that she didn’t just live the life but she expressed it in her works. The male artists of the Pop movement, with the exception of her friend Peter Blake, used the imagery of popular culture as a mediated comment on the visual world about. You always feel in their work a standing back by the artist from the work while he considers its composition and effect.

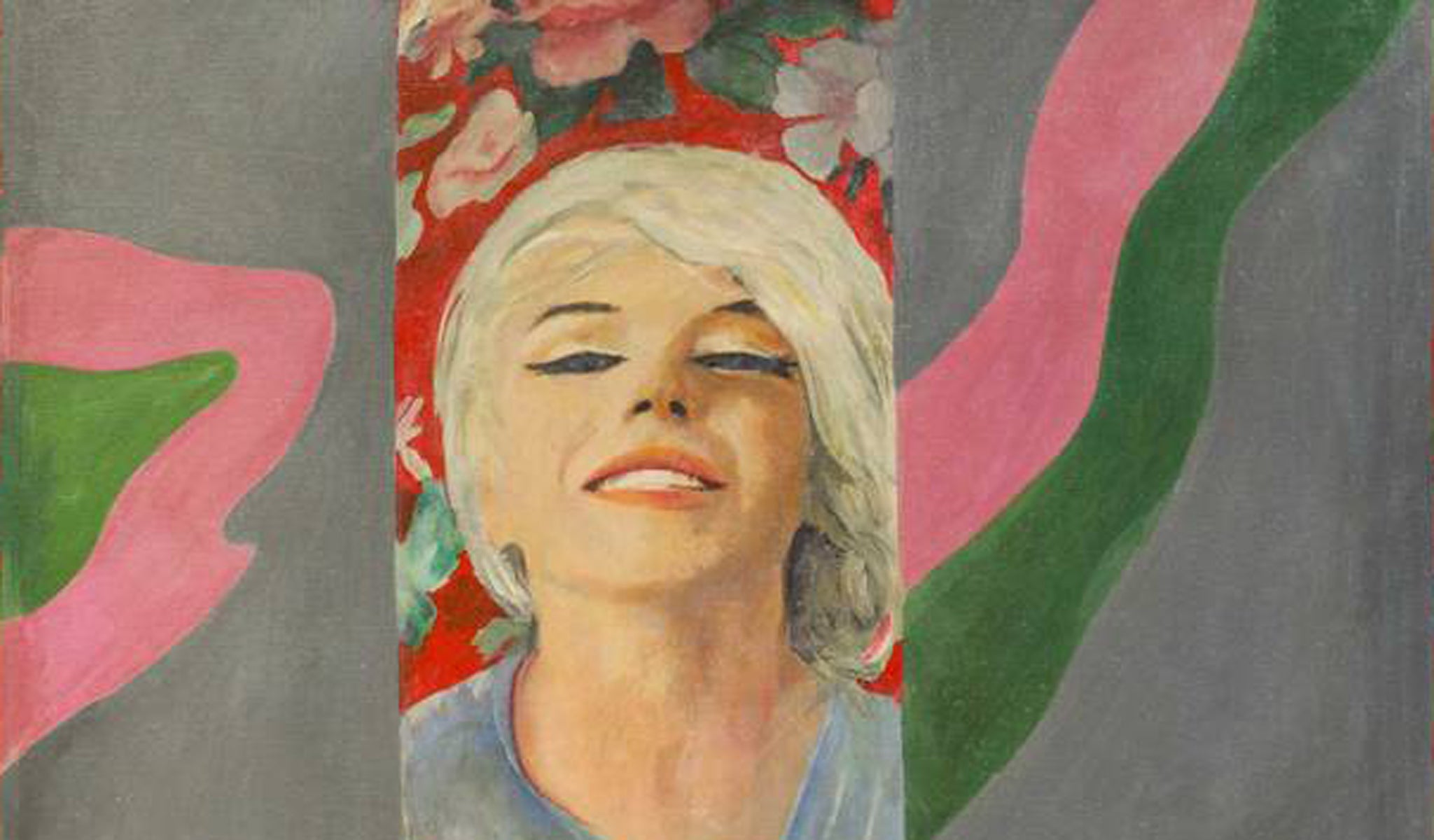

With Boty you feel the artist herself in her emotions. From the moment she started introducing colour into her collages in an expressive manner from 1961, her works are charged with an air of freedom if not abandon. My Colouring Book from 1963, takes the popular song of the time and realizes its lines –“this is the room I sleep in and walk in and weep in and hide in that nobody sees”, “these are eyes that watched him as he walked away, colour them grey” and so forth – in images that are both literal and moody. The Only Blonde in the World (1963) is part of a series on her heroine Marilyn Monroe in which the ill-fated blonde star is seen striding in the narrow vertical of green abstract painting.

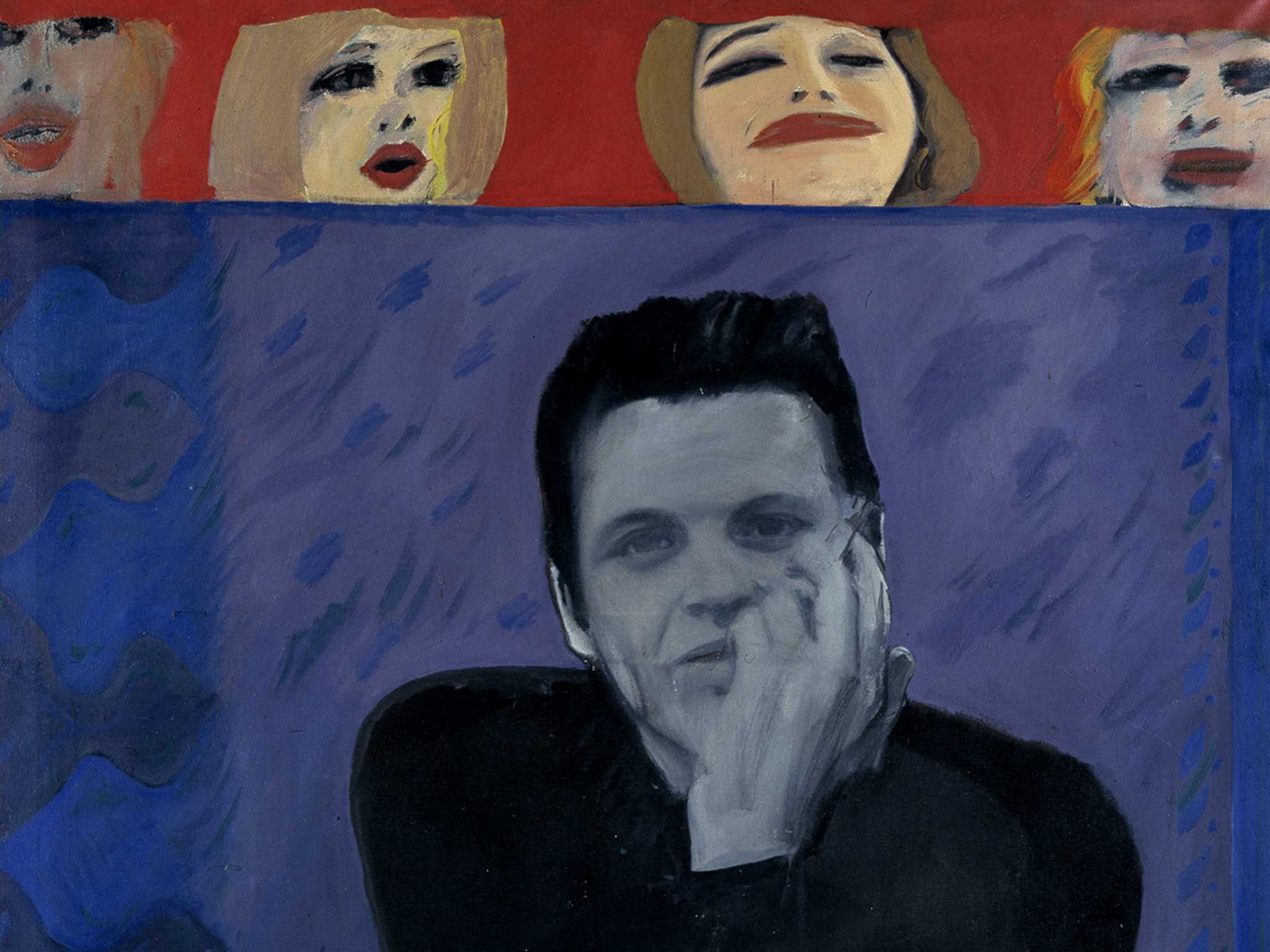

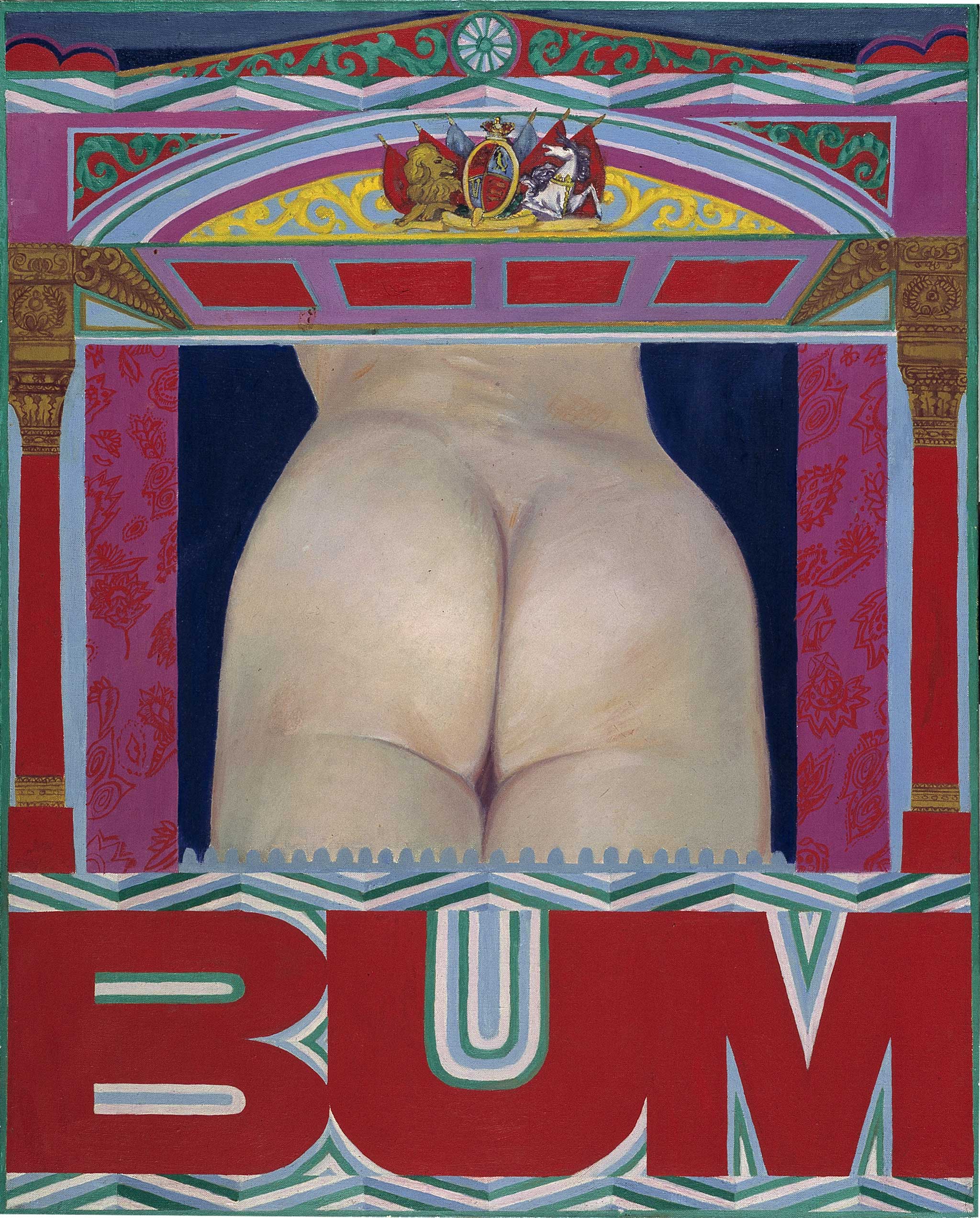

As she matured so she grew bolder in her representation of women’s desires and men’s objectification of them. 5-4-3-2-1, after the song by Manfred Man, has a yellow banner trumpeting “OH, FOR A FU…”. Portrait of Derek Marlowe with Unknown Ladies sees the subject painted in seductive tones from a publicity photograph while red-lipped, roughly presented female faces leer out from a strip above. It’s a Man’s World II has a central strip of erotic female nudes set against the lake and pavilion of a country estate. Her last picture, commissioned by Kenneth Tynan for his notorious cabaret, Oh! Calcutta! is entitled BUM (1966) and is of just that – a nude female rear painted with high realism and framed by a proscenium arch and the colours of the cabaret.

Her death was tragic. Married to the literary agent Clive Goodwin after a whirlwind romance of only 10 days (she said she married because he was one of the few men interested in her brain) and pregnant, she went for a prenatal check-up to be diagnosed with cancer. She refused treatment for fear that it would damage the foetus and died a few months after giving birth to a daughter. Her paintings and other material ended up in her brother’s barn.

Could she have gone on to bigger things? After this exhibition it is hard not to believe so. Her interest in politics was burgeoning, as a striking picture of Kennedy’s assassination, Countdown to Violence, and a forceful vision of the Castro revolution, Cuba Si, would suggest. But it is her panache with a photorealist style of figuration set against bold colour and pop imagery which hold such promise for the future.

It’s not a big exhibition. Given the paucity of her surviving work it could not be otherwise. But it is one which leaves you eager for more, more of the pictures she did paint and the ones she didn’t live long enough for.

Pauline Boty: Pop Artist and Woman, Pallant House Gallery (01243 774557) to 9 February

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments