Norman Rockwell: An artisan, not an artist

A new exhibition of Rockwell's illustrations shows he was a skilled oil painter, but his relentless optimism soon starts to grate, says Adrian Hamilton

Your support helps us to tell the story

This election is still a dead heat, according to most polls. In a fight with such wafer-thin margins, we need reporters on the ground talking to the people Trump and Harris are courting. Your support allows us to keep sending journalists to the story.

The Independent is trusted by 27 million Americans from across the entire political spectrum every month. Unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock you out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. But quality journalism must still be paid for.

Help us keep bring these critical stories to light. Your support makes all the difference.

Dulwich Picture Gallery has chosen to launch its centenary celebrations for 2011 with an exhibition of the US illustrator, Norman Rockwell. Not everyone's choice for such an important year, admittedly.

On this side of the Atlantic at least, and to the taste of most art critics in America, Rockwell tends to be dismissed as a schmaltzy sentimentalist, the man who reflected middle America as it wanted to be seen – patient, well-intentioned and humorous – rather than as it was during the years of depression and war.

And yet it is a choice that fits the Gallery's policy of developing self-generated exhibitions of areas and artists that the bigger galleries and conventional tastes have ignored. In recent years it has particularly concentrated – for reasons of commercial support as much as artistic taste, one sometimes suspects – on American artists and illustrators in particular. Saul Steinberg, N C Wyeth and family and Winslow Homer have all been subject to individual, and good, exhibitions over the past few years.

Rockwell at least has the virtue of being probably (one never knows with changing generations) the best-known illustrator in America. An exhibition at this time also has the advantage of coming, in a postmodernist world, when there have been calls for his re-evaluation in the canon of American art. "Rockwell is terrific. It's become too tedious to pretend he isn't," wrote the New Yorker art critic Peter Schjeldahl.

"Terrific" isn't the same thing as good, of course. Much of one's resistance to Rockwell's work comes not simply from the sense of his being too sentimental but because of the sheer polish of his finish, the glossiness not just of his figures but the glossiness of his view.

That may be unfair. Norman Rockwell, who did cover pictures for the US's most popular magazine, the Saturday Evening Post, from 1916 until 1963, never pretended to be anything other than an illustrator. "If it doesn't strike me immediately," instructed an early editor, "I don't want it. And neither does the public. They won't spend an hour figuring it out. It's got to hit them."

And that is what Rockwell did, so successfully that he increased the sales of the publication each time he did the cover. He could hardly be blamed for giving the reader what they wanted. It's an academic presumption that artists are there to subvert the prejudices of their audience. The point this exhibition, organised by American Illustrators Gallery, New York, with the National Museum of American Illustration (NMAI), is not to suggest that Rockwell was more than his professed trade but that he was supremely professional at it.

One surprise to me, and probably to many who visit the gallery, was that Rockwell painted all his illustrations in oils. He completed more than 5,000 of them, each preceded with careful drawings and sketches. Photographs of him at work, and his own drawing of himself, show him with his easel pinned with photographs and scraps as he worked on the final compositions.

With considerable effect, Dulwich places the oils and sketches along the right of the series of rooms, while on the left wall it presents a whole series of his magazine covers. The original works are fascinating, the colours fresh, the paintwork rapid and fluid. Painting in oils gave him the textures, particularly of the flesh, which make his work so warm in their realism when converted to the printed page. They also show how deeply versed he was in artistic tradition, particularly the work of the Flemish and Dutch masters, while the few watercolour sketches display a quickness of observation that makes them attractive in their own right.

Had Rockwell sold his paintings as paintings rather than illustrations he would, like Jack Vettriano, have been a highly popular artist and for similar reasons. He gives a simple, strong image that proposes a story that involves the viewer in imagining it. Rockwell's works never needed a caption, although they sometimes had one. They are, obedient to his editor's commands, self-explanatory on first view.

The element he adds, and the element that helped him achieve the fame that most of his contemporary illustrators lacked, was his sense of the humour of shared humanity. There is always in his work a certain wryness, the boy trying his first shave with the dog looking straight at the viewer, amazed at the action of his master; the lonely fisherman carrying on in the pelting rain, his pipe upside down to keep it dry; the two charwomen in the theatre reading the programme of a grand show they could never hope to see.

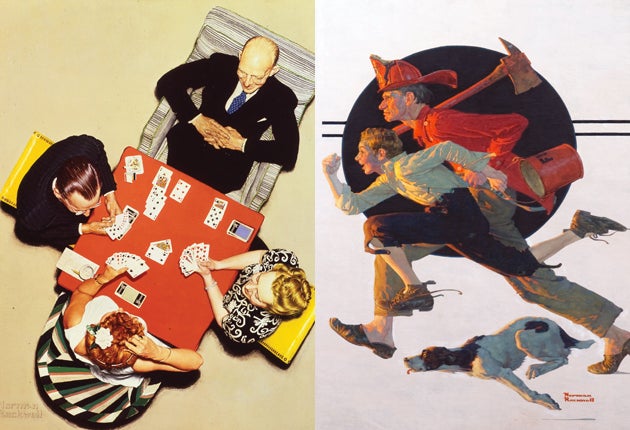

And at times he comes up with stunning compositions. There is one bird's eye view of a bridge game that shows not just the artist's assiduity in research to get the details right but also a geometry and confidence in colour that is quite startling in its freshness. Rockwell, driven by a fierce desire to be pre-eminent in his trade, however, never seems to have wanted to be an "artist" in the way that so many photographers privately try. He was a perfectionist in his craft not a creator searching for expression, as ready to undertake advertising commissions as illustrate romances.

Whether Rockwell's claim to lasting status is altogether helped in this exhibition by the great wall of covers facing his oil studies and finished paintings is doubtful. Most of his paintings work well in print, but when he is most inventive as a painter, as in the Bridge Game and the oil study for Breakfast Table Political Argument, the liveliness of his colours is lost on the page.

By the 1960s, Rockwell, whose wife had died, gave up the Saturday Evening Post to develop a different, more political type of illustration. It was partly out of a desire to engage with issues such as desegregation (he was on the side of civil rights out of an old-fashioned belief in equality) but also, I think, because Rockwell, who suffered bouts of severe depression, had achieved the success he had set out to gain, had written his memoirs, become a public figure and was losing his passion for perfection.

His attempt at political engagement only served to show up his limitations. He visited Africa and Russia for Look magazine. But his work is oddly stilted. As earlier Post covers tended to prove, Rockwell didn't really do anger or passion. He believed in politeness and a relentless optimism that becomes depressing when seen in volume. He lived on until 1978, but by then the world of magazines, as art, had spun way out of the ambit of his limited vision .

It's possible that a new age of recession will bring a revived appetite for his optimism and humour, as it did the last time round. But I can't see Rockwell ever being regarded as more than a supreme commercial artist of his time.

Norman Rockwell's America, Dulwich Picture Gallery, London SE21 (020 8693 5254) to 27 March

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments