Marlene Dumas at the Tate Modern: Sex, social inequality and human spirit explored superbly

It's a fitting tribute to the world's most expensive female artist

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.I have been looking forward to the Marlene Dumas exhibition at the Tate Modern since it was announced. Recently, its programme has been one of dead male artists – Matisse, Munch and Malevich to name a few – great artists all; but finally a live woman painter. Dumas is an artist full of contradictions; her subjects swing between saints and sinners, lust and innocence, all very contemporary concerns. After I have walked through the show I am relieved to see that my expectations have been satisfied and even surpassed.

Dumas was born in 1953, the youngest of three – she has two older brothers – on a farm in Kuilrivier in semi-rural South Africa, into a repressive political regime where images were censored: a photograph of Nelson Mandela could not be published. She loved to draw and soon developed a capacity for creating likenesses in a few lines, a talent used both to entertain her friends and to create her own inner world. Her knowledge of art was mainly through illustrated books, thus removed from the original. She moved to Europe in the summer of 1976, choosing Amsterdam as a “tolerant” province of Europe, and because of its language links with Afrikaans.

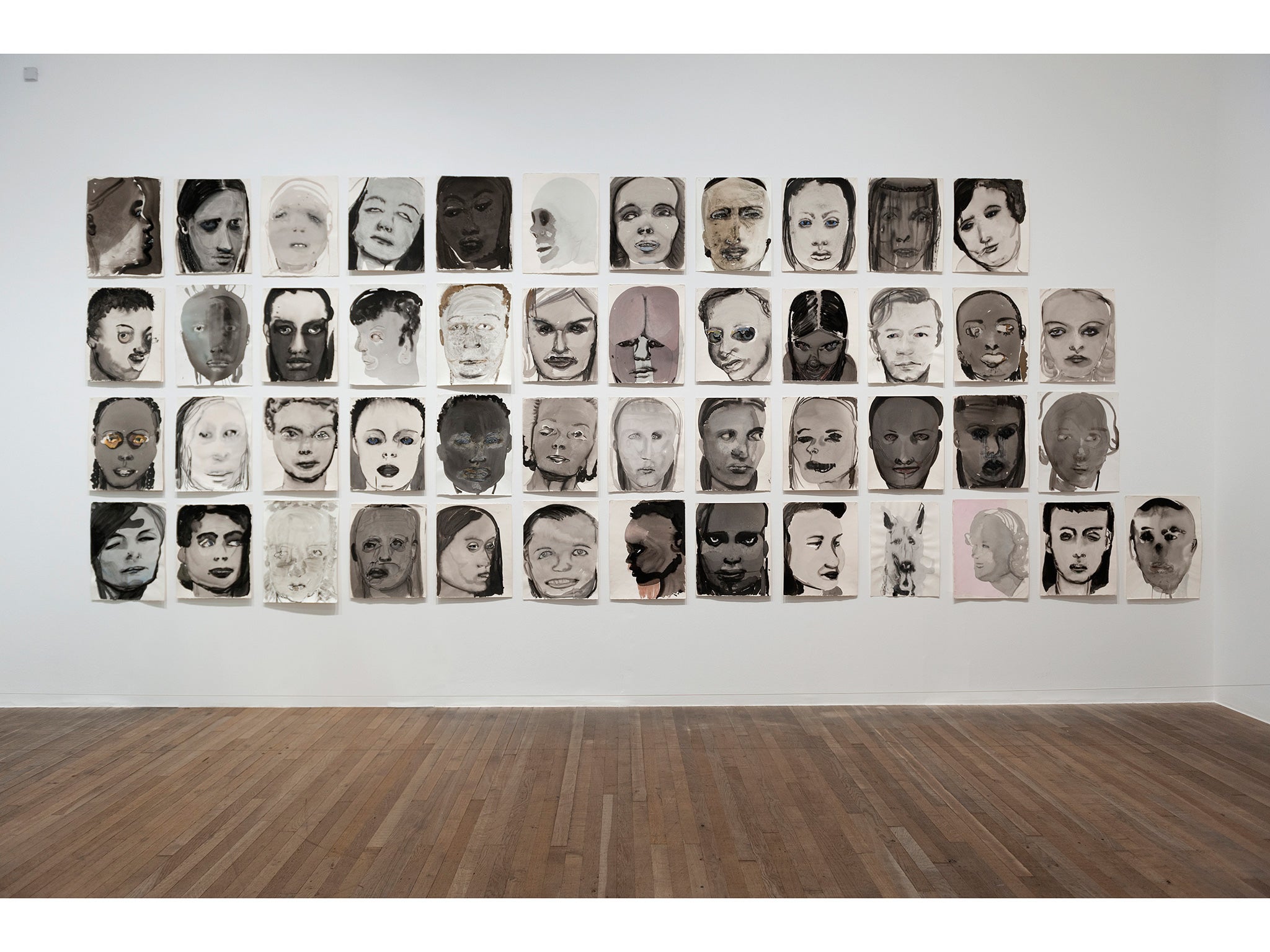

The Tate show is installed roughly chronologically, although the scene is thoughtfully set with a wall of portraits Dumas calls Failures. These drawings span from the Seventies until today and engage with her determination to depict more than “mere” likenesses. It shows working and reworking and, in certain cases, frustration. Eyes are gouged out as if their information is frustratingly unobtainable to the artist. Her early work displayed here is compressed into a few rooms showing her transition from a student in South Africa, through tremulous drawings of trees and landscapes and a composite time line, maddeningly hard to read. There are collages with torn and pasted images from magazine hinting at the source material that would become central to Dumas.

It is not until the third room that we encounter Dumas grappling with paint, in a group entitled “The Eyes of the Night Creature”, which includes Evil Is Banal (1984), a stunning self-portrait with flaming hair and ghostly lips. Most disturbing is Martha – My Ouma (1984), hung high on the wall as if looking down on the viewer, eyes milky and seemingly unseeing, the wattles of age emphasised, the whole work in a freezing ghostly blue. She says to me: “I always have a sympathy and gentleness… I work about loss and grief and I would rather work with them.” Each painting in this group demonstrates a different and seemingly effortless technique. Sigmund’s Wife (1984), her face an improbable composition of ramped-up colour, is most clearly an homage to expressionism, an influence that Dumas freely admits.

Dumas left South Africa at a time “when the townships were burning”, so it is not surprising that Black Drawings (1991-92), when shown in Washington DC, was accompanied by a wall plaque explaining it to the viewer, who might have assumed that this was her reaction to apartheid. Dumas is clear that these are “merely” images, based, as all of her work is, on photography (“she does not paint from life” I am told by one of the curators). This group, like the paintings before, is also a celebration of a new technique, one of the first times that she used a large amount of black ink. The drawings on closer inspection capture that universality of physiognomy. This wall is a celebration of blackness in the broadest and best sense.

During the early 1990s Dumas was also working on a series including The Image as Burden, a small work from which the title for the show is taken. When I ask her about the title, she says, “With text, it is the titles that make people look at in a certain way.” It also chimes with the revelation that it is a struggle for her between the image and realisation. Images present themselves to her in different ways and “sometimes people write that I stay so close to the photograph, and sometimes I do because why not? And sometimes it goes another way; sometimes it is the image for myself”. The Image as Burden, like so many of this period, is ambiguous, the title giving a clue – or not. The two figures in question – a man I surmise, although there are no genitals showing – carries what I construe as a woman. Is he rescuing her? But the large menacing black hand and her blue face opens the door for other meanings. It is an arresting work, but, like its title, opens the door for uncertainty. In the room entitled Magdalenas we encounter the most bizarre image in the show. Here, among a group of long slender improbable Magdalenas, is Great Britain (1995-1997), two canvases hung contiguously. On the right is a portrait of a young Princess Diana dressed in sugary pastel pink on a maroon gilt chair, her eyes detached from the viewer, thinking private thoughts. She is next to a portrait of Naomi Campbell wearing merely a white thong. The juxtaposition can be seen as a comment on the multiracial mix of black and white. It makes for uncomfortable viewing, the fissures of contemporary Britain clear to see.

It is easy to become engrossed in the subject matter of Dumas’ work. It is hard to talk about the pleasure of paint without sounding pretentious in a world inhabited by facts and short attention spans, but with this show it is important to point out the pure skill and sensuality of the medium that Dumas uses. An arresting work like The Wall (2009) recalls her words: “It is not that I come out of a realistic tradition. I actually come out of an expressionistic one, but I like the tension between the actual things that happen in the world.” Here is a portrait of five religious Jewish men seen from the back and in profile, engrossed in their private rituals. There is pain in this work but there is pleasure too, in the beauty of the towering so-called “security wall”, giving the viewer the perspective of the scale of humanity. It is the painting though, the fluid black, the stony wall in the scrabbling dry marks that draws us into this work and makes us pause. Historical painting is digested and processed in these works; the great paintings of Goya and in particular the blackness of Manet are referenced, but Dumas makes the work seem effortless.

It is hard for me to choose a favourite in this extraordinary show, but I admit that The Painter (1994), shown on the cover of the catalogue (I am not alone in my admiration), encapsulates what I love about Dumas. There is a blankness in the expression of the naked child, inspired by a photograph of her own daughter covered in paint, a mixture of vulnerable innocence and over-knowingness. Saint or sinner? The title is perhaps a clue to the fact that the figure’s hands are drenched with colour, as if she has done some serious finger painting.

Dumas is not that well known in the UK although she has the record for the highest price achieved for a living woman artist with her work The Visitor (1995) having sold in auction for £3.1m. Weeks before the show opened in London there was a news story of the Tate’s censorship of an image exhibited in the show in Amsterdam. The image in question, D-rection (1999), a man with an erect member, was supposedly withdrawn. The story was untrue. Dumas herself, having drawn up the list of works to be shown in different spaces, had omitted this one. There is a discreet side gallery of Dumas’ more pornographic works. Taken from Polaroid images, often by Dumas herself, here are woman shown in graphic detail, often from behind, pleasuring themselves. Dumas says in the catalogue that she had taken a two-year ethics course with Professor Marthinus Versfeld, who taught her that “all failures of civilisation are erotic failures. Plato and Augustine knew this and we cannot afford to let this failure perish.”

Marlene Dumas: The Image as Burden, Tate Modern, London SE1 (020 7887 8888) to 10 May

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments