Marilyn Monroe comes to Merseyside as Andy Warhol's exhibition lands at Tate Liverpool

Warhol changed the face of modern art by turning the idols of his day into commodities and elevating everyday objects into icons. Karen Wright on a heady show at Tate Liverpool

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

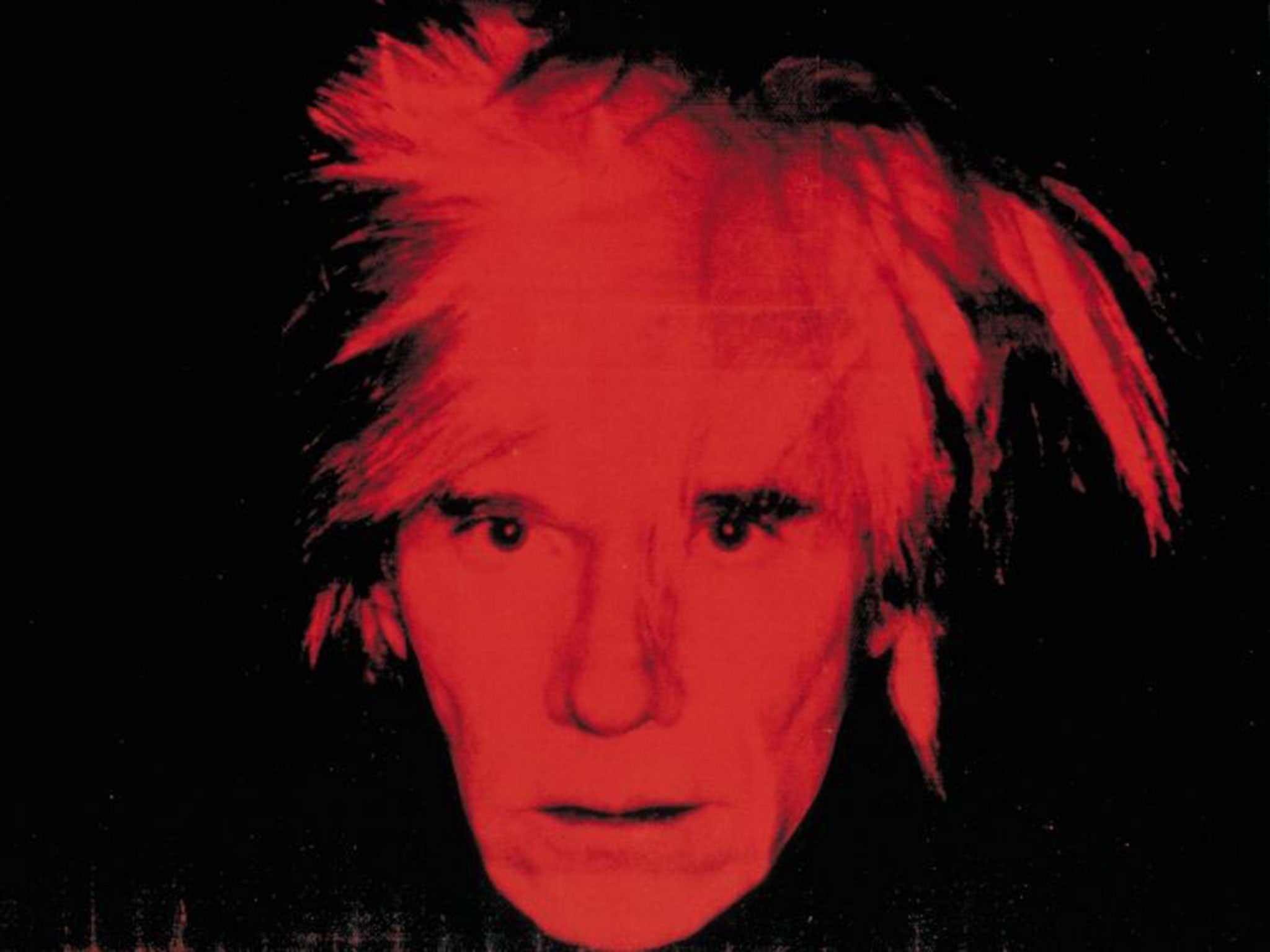

Your support makes all the difference.Andy Warhol was the most influential artist of the 20th century, and Tate Liverpool presents a spirited exhibition to support this premise. In the past I might have given that label to Marcel Duchamp, but Warhol’s co-option of subject matter, his use of different materials and ways of disseminating his ideas and persona through multiples, publishing, film and television laid down the pattern sheet for today’s aspiring artists – having already influenced contemporaries such as David Hockney and Jeff Koons.

Even the naming of his studio the Factory, and his employment of assistants – many of them artists – as the solution to producing enough to withstand market pressures, is reflected in contemporary practice. Warhol also came up with some of the most memorable quotes of the 20th century, such as “Art is what you can get away with” – a motto you feel many contemporary artists cling to tightly.

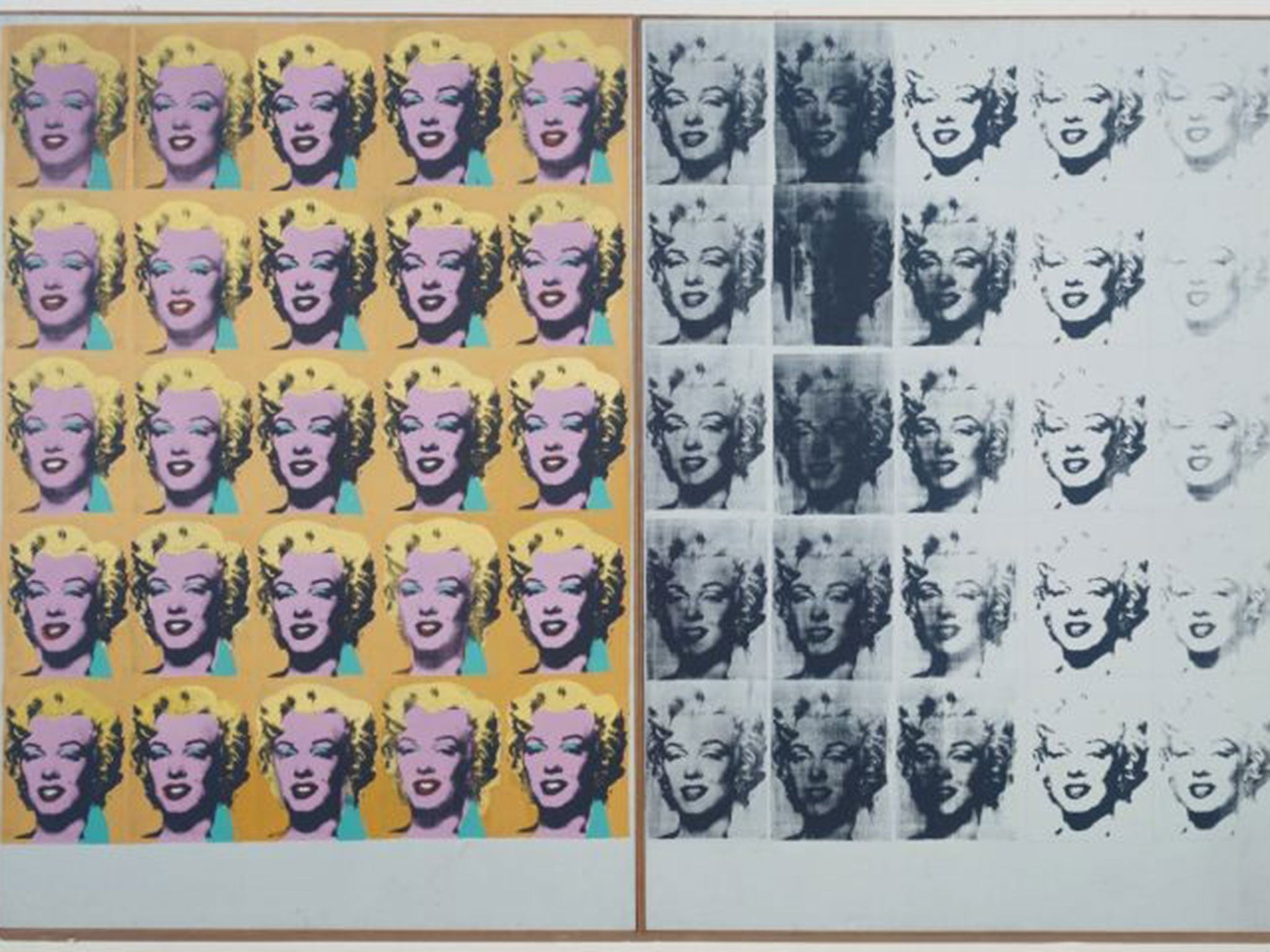

Entering the Andy Warhol show in Liverpool, quickly scanning for the icons – Marilyn Monroe, Mao and Elvis – I see they are all accounted for. On a separate wall, The Beatles, Liverpool’s personal icons, smile widely against a riotously colourful background. It is an image I have not seen before, a screen print that was a commissioned for a book jacket, I am told, by the affable curator, Darren Pih.

The theme of this show, from which the exhibition takes its title, is transmission or dissemination. Pih says it is “to show his [Warhol’s] relevance now in the age of the internet”. It’s the first major solo show in the north of England to focus on Warhol’s expanded practice, or as Pih defines it “multiple platforms”: painting, design, publishing, movie-making, photography, commercial commissions and endorsements. The works draw largely on the Tate’s own collection, with carefully considered loans largely from the Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, the city in which Andrej Warhola Jr was born in 1928. His mother was famously supportive of her young son’s preoccupation with all things visual and encouraged him by buying him a film projector aged six, allowing him free range of the visual materials – comics, film magazines – that would continue to shape his vision.

Warhol moved to New York after completing his studies at the Carnegie Institute of Technology and approached the art directors of major fashion magazines. He was commissioned first by Glamour and then quickly by others, including Vogue and Harper’s Bazaar. He “Americanized” his name to Andy Warhol in 1949. By the late 1950s he was one of the highest-paid commercial illustrators in the USA, and seeing the brand potential in his name, he established Andy Warhol Enterprises. In 1958 the phrase “Pop artist” was coined in an essay by English art critic Lawrence Alloway, a label that was to stick to Warhol and his peers, including Roy Lichtenstein.

The Beatles illustrate one of the interesting themes in this show: Warhol’s commercial work. He started originally as a graphic artist and could well have carved out a successful career in this discipline. His drawings, here chosen as studies for his commercial projects, book jackets and record covers, show the deliberately improvisational-looking “blotted” line that feeds into his painting like Advertisement (1961) of this period.

There is a wall of record covers including the iconic Rolling Stones Sticky Fingers cover, trouser zip and all, and the Velvet Underground banana peel that was to become more famous as an object then the music contained inside. This music wall illustrates not only the commercial quality of much of Warhol’s work but also his crossover into the music of the day.

![Andy Warhol, [no title] 1971](https://static.independent.co.uk/s3fs-public/thumbnails/image/2014/11/09/15/warhol4.jpg)

Interview, the magazine founded by Warhol to include his interviews with celebrities, still exists today in a rather less sparkly form and is represented here with a wall of its glam stylised covers. Warhol loved hanging out with rich famous people and they loved hanging out with him. By the later 1970s he was a regular attender of Studio 54 even though he famously rarely spoke much on these occasions.

In 1963 he set up his now famous studio and named it the Factory, in a loft on New York’s East 47th Street before in 1968 moving to 33 Union Square downtown. Alongside the work done there, people came to hang out, including Edie Sedgwick, who became so famous for her participation at the Factory that the biopic Factory Girl was made of her life in 2006. In 1968, Valerie Solanas, a Factory visitor, hanger-on came to the factory and shot Warhol and art critic.

The first room in this show sets up the argument for Warhol as the Pop artist who first saw the value of both co-opting the icons of the day as well as rising the common object to iconic status. There is a Marilyn Diptych (1962) as well versions of Campbell’s Soup (1968). There are Three Brillo Soap Pad Boxes (1964/68). The various use of artistic mediums that Warhol employed through his life are visible here. He was the first artist to use the mechanical silk screen, utilising the technique in 1962, screening and stencilling directly on to paper, linen and canvas – and in the case of the Brillo Boxes, on to Masonite. This technique led to the multiple being raised to a new level, especially in the case of some of his subjects like Mickey Mouse, sadly not represented here, covered with shiny diamond dust. Do It Yourself (Seascape) (1962) reflects the days many American children spent painting on pre-stamped canvases with small pots of paint.

Pih is determined to show the crossover with broadcasting and projecting that interested Warhol in the 1960s. In 1963 he made Sleep, his first film, using a fixed camera and deliberately no editing, (the film lasted five interminable hours) a technique he continued to use on his most famous film Empire (1964), in which the camera was fixed on the iconic building for over eight hours. He also accepted commercial commissions for print and television including a series of advertisements for Schrafft’s restaurant in which the fixed camera was focused on one of their yummy sundaes. In 1980 he had established Andy Warhol’s TV, an interview talk show on cable television that lasted until 1982.

In 1967 while Warhol continued to paint cultural icons – the Marilyn portfolio composed of 10 different screen prints – he also created Electric Chair Portfolio (1971), a silk-screen series of electric chairs, capital punishment being a subject that gripped America’s liberal classes. Here there is a selection of the series in their shockingly inappropriate sugary colours, and Warhol’s cynical words ring in my ears: “You’d be surprised how any people want to hang an electric chair on their living-room wall, especially if the background colour matches the drapes.” It is easy in this day of C-list celebrities to forget that while Warhol was no doubt obsessed with glamour and money, he famously said “in the future, everyone will be famous for 15 minutes”, he was also concerned with the explosive events that were shaping America’s history.

Warhol was a great artistic experimenter and while there is some photography – he photographed and selfied himself constantly – sadly some of his best experiments are missing in this show. Along with the lack of diamond dust there are no oxidation works. Created in the 1970s, these extraordinary works, made by urinating on the surface chance events, echo the two Rorschach images here. But there is perhaps Warhol’s most prescient work, Dollar Sign (1981): the symbol of what his work was to begin, an indicator of the wealth of his collectors and their obsession with the buck, represented in the now almost comical competition as to who has the biggest, most colourful Marilyn, or the best flower work. You get the feeling he would have revelled in seeing his prices shoot up and his paintings reach ever dizzying heights in the auction rooms after his death in 1987.

In 1965 Warhol was introduced to Paul Morrissey who collaborated with him on his films. He met the members of the Velvet Underground and they became friends and visited the Factory on a regular basis. In 1966 he worked with the band – and with guest Nico – on the Exploding Plastic Inevitable, presented here in Liverpool as an immersive environment complete with films, soundtrack and glitter ball. Standing in a darkened room on the fourth floor of Tate Liverpool, I am transported (almost) back to the glamour of a smoke-filled club in 1970s NYC; getting the experience of art mixed with throbbing music is a heady experience. Take thee to the docks.

Transmitting Andy Warhol, Tate Liverpool (0151 702 7400) to 8 February

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments