Howard Hodgkin's journey into the art world

Before his death this month, Howard Hodgkin was preparing the first ever exhibition devoted to his portraits. Paul Levy recalls the man who cared much more about his family and friends than being part of any movement

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

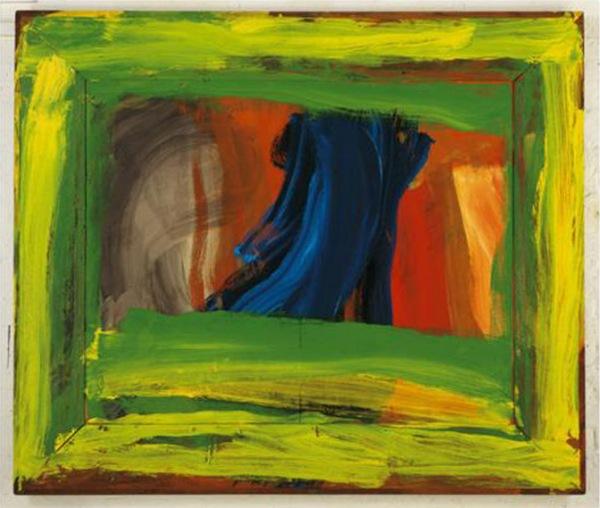

Your support makes all the difference.Howard Hodgkin: Absent Friends, an exhibition of the painter’s portraits, opens at the National Portrait Gallery on 23 March. There’s a sorrowful irony about the title, as Hodgkin, one of the artistic giants of the late 20th and early 21st centuries, died, aged 84, on 9 March. Probably as erudite as any artist in history, he was a genuine intellectual in the European and American traditions, a connoisseur with an unsurpassed eye, perfect visual recall, and an incessantly obsessed collector. The longing “for acclaim” and “taste for public honours” noted by his friend Bruce Chatwin were merely the measure of his ambition.

Hodgkin never belonged to any movement or school, and his paintings – almost aggressively – defied categorisation. As he wrote: “I am a representational painter, but not a painter of appearances. I paint representational pictures of emotional situations.” Another friend, Susan Sontag, remarked that, as the emotions depicted were “the artist’s … in this sense, all the pictures are autobiographical”. Their “subjects” are friends, husbands and wives, lovers – in their rooms or gardens – as well as places he had visited and, wrote Sontag, “lovemaking and dining and looking at art and shopping and gazing out over water”. As you might expect from this, Hodgkin had a remarkable memory, and also had a gift for love and friendship.

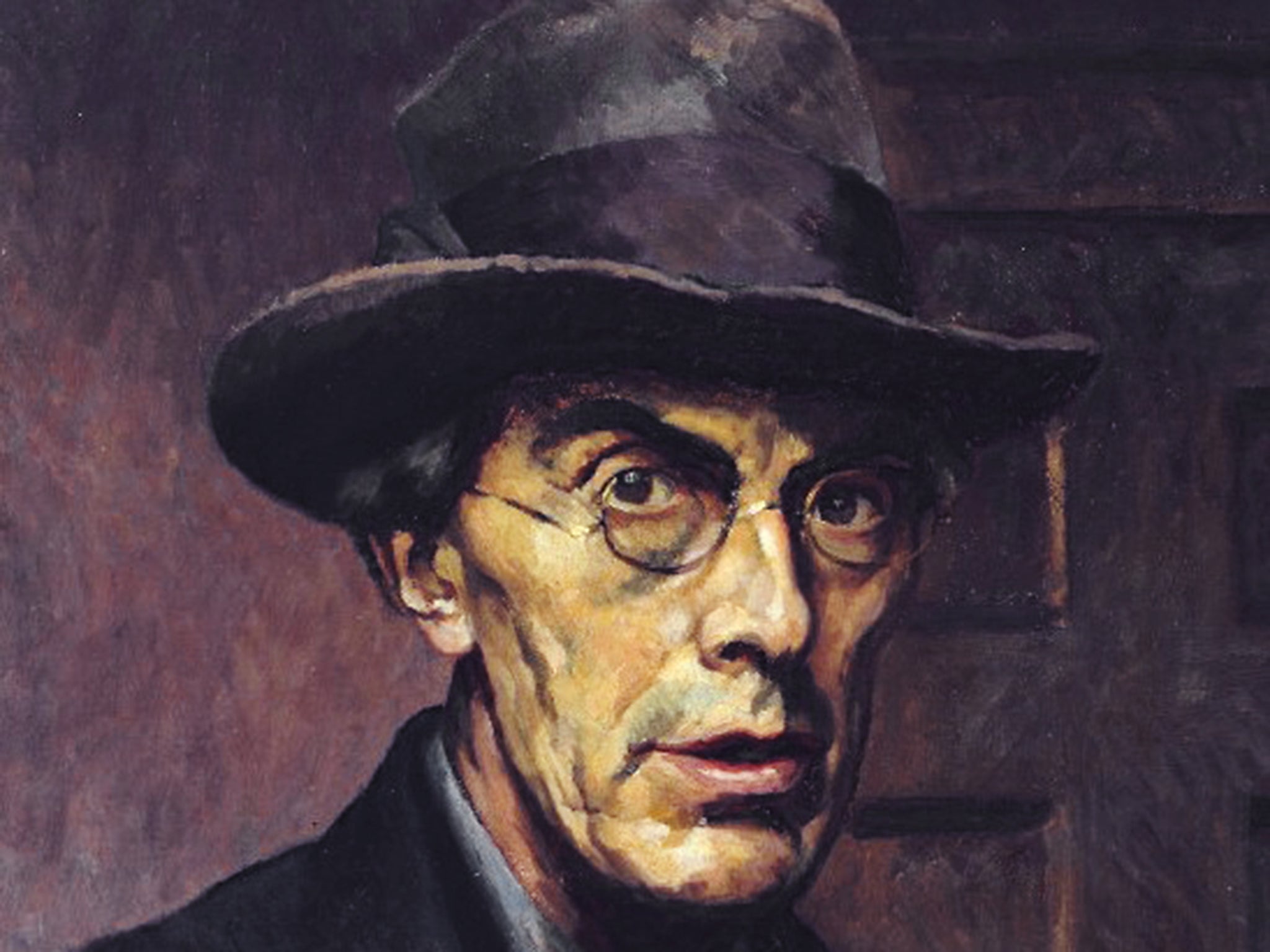

Hodgkin was destined for distinction – he was bred for it. He was named after his ancestor Luke Howard (1722-1864), the classifier of cloud formations. The Hodgkins were one of those great Quaker families that made up some of the dynasties of what Noel Annan termed the “Intellectual Aristocracy”. There are currently eight Hodgkins in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography – seven are certainly ancestors or relations (and probably so was John Hodgkin, who died in 1560, Dominican friar and bishop-suffragan of Bedford). The family tree also included the discoverer of Hodgkin’s disease, a Nobel Prize winner for medicine and, though Dorothy Crowfoot was only a Hodgkin by marriage, for chemistry. The Bloomsbury critic and painter Roger Fry was a relative, as was the poet Robert Bridges. (I’ve published a chart that shows how the Hodgkins were distantly connected to the philosopher GE Moore, to the Wedgwoods, Darwins, Keyneses, Stephens, Woolfs, Bells, Grants, Stracheys and Bertrand Russell.) Howard’s academically successful father (he could have been an Oxford don) was Eliot Hodgkin (not the painter and collector of that name, 1905-1987, who was a cousin born about the same time), a businessman, an avid Alpine gardener, distinguished horticulturalist, and, Hodgkin told me, with the tears that came frequently and easily to his eyes, spent the War years in Sefton Delmer’s black propaganda unit.

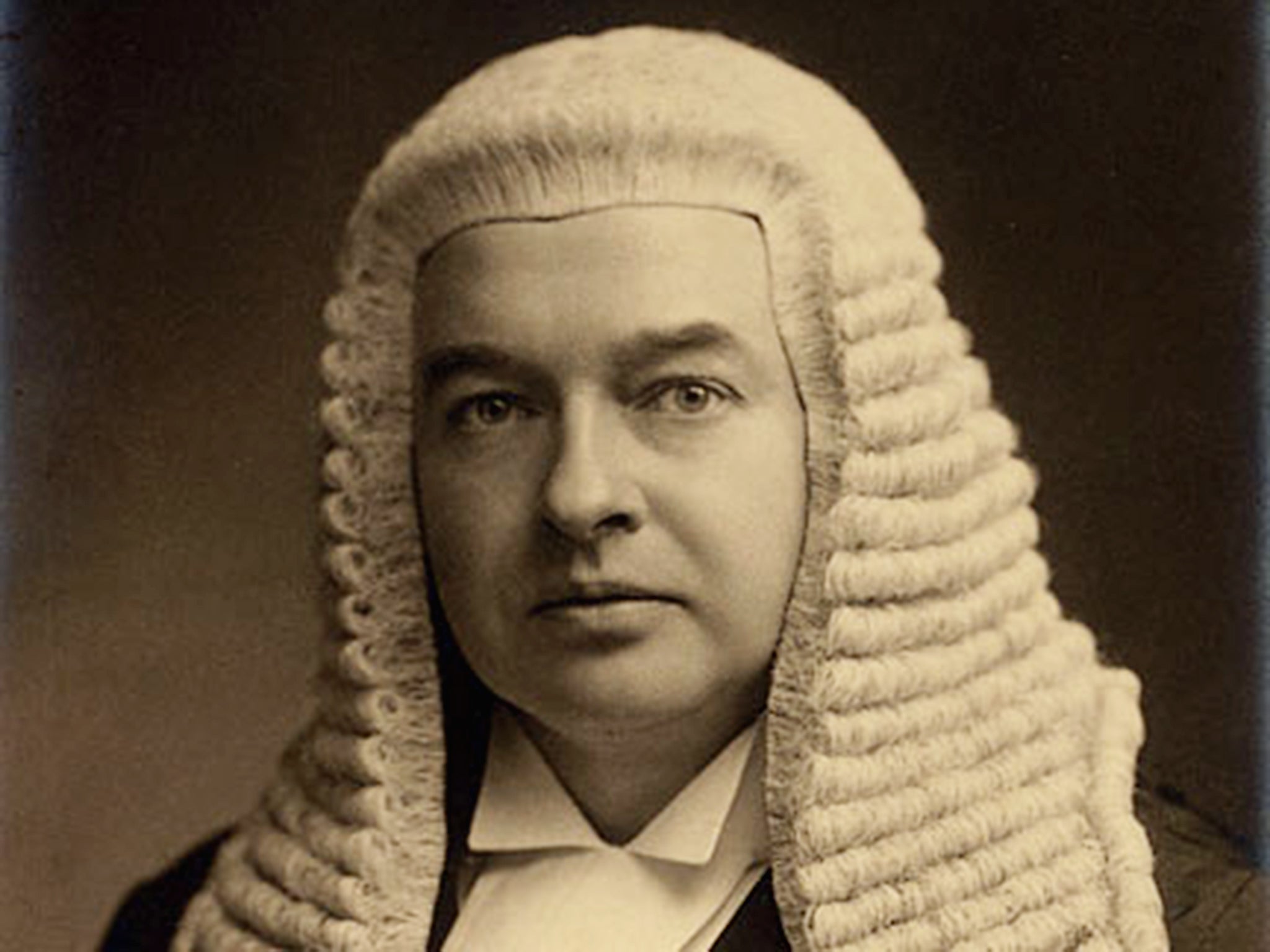

His mother was from a different stratum of the English upper crust. His maternal grandfather was the unpopular Lord Chief Justice of England and politician, Gordon Hewart, first Viscount Hewart (1870–1943), who coined the aphorism about justice needing to be seen to be done; and his mother (whom he and his older sister, Ann, called “M”) was the Hon Katherine Mary, who read greats at Oxford and became a botanical draughtsman painting watercolours for Kew Gardens. Her handsome elder brother was killed at the very beginning of the First World War; her younger brother inherited the viscountcy but went mad and had to be cared for all his life.

Gordon Howard Eliot Hodgkin was born in Hammersmith. “When I was six,” he said, “I drew in coloured crayons a picture of a woman with a very red face; and I was looking at it when somebody asked, ‘What do you want to be when you grow up?’ And I said, ‘a painter’.” His childhood memories were acutely visual. He also remembered floating in a large blue bath in a hotel in Cologne that had a picture of the Führer in the dining room, and a holiday in Carinthia during the Anschluss when his German nanny displayed a Nazi flag. He was sent to the Froebel school in St Peter’s Square for about two years, before, aged 7, he was evacuated, from 1940-43 with his mother and sister, straight into the world of F Scott Fitzgerald.

At first they went to the large house of John W Davis, elderly family friends in Long Island, New York, where the wife had had an early and unsuccessful facelift. “My mother was having an affair with a woman called Betty Babcock,” he told me, “a Standard Oil heiress, a very nice woman indeed”, and they moved to her house. He attended Greenvale School there, beginning in the fifth grade – very far ahead of the American children – and “I learned a lot about American history”, though the art teaching was poor, and the woman teacher disliked Hodgkin’s self-confidence and precocity. He also remembered being stimulated by seeing pictures by Stuart Davis, Matisse and Picasso at the Museum of Modern Art, as well as going to the Metropolitan Museum.

“We came back in 1943, in the middle of the U-boat war.” The reason was that his grandfather, Lord Hewart, who had remarried, had just died. Hodgkin’s father was one of the executors of his father-in-law’s will, and insisted that they return because of problems with the will and the new Lady Hewart, wishing his mother to “fight her corner”. The crossing took 23 days, and Hodgkin could recall the “equinoctial gales” they ran into “with appalling clarity”. He remembered “various vignettes” of that journey, but assured me that he’d never painted those moments, not even in the several pictures he’d done involving storms.

That autumn they lived with Hodgkin’s grandmother, Florence Hodgkin (“Irish, and a fabulous person, claiming to be the thirteenth child of a thirteenth child”, he told Colm Toibin), outside Reading, and he was sent to board at the fairly new (1934) prep school, St Andrew’s, Pangbourne. Quite soon he ran away from school, the first of many such adventures, because he “wanted to be an artist”. as he told the “charming, elderly policeman” who found him, and took him seriously, though he returned the boy to the school. The “quite good” art teaching at St Andrew’s was partly by the cartoonist Peter Probyn, though Howard’s best subject by far was English. His parents lived in rented accommodation outside Henley, because his father was doing “his unpleasant spy work”. He continued his habit of running away at Eton and Bryanston. At Eton he was in RJN Parr’s house. (Michael Holroyd described him as, “Purple Parr, a portly, well-waistcoated and bespectacled man with a very red face, taught mathematics. He was a discouraging man. Even when he said something that was intended as praise, it turned out disparaging. He couldn’t help himself. He’d say things like: ‘You did rather well – but of course it was a particularly easy paper this year’.”)

He lasted at Eton a full year plus one Michelmas Half. For the first year he worked in the Drawing Schools, “made friends with the art master, Wilfrid Blunt, quite quickly”, and painted pictures like those he’d done in America. These include a figurative work when he was about 16, the extraordinary Tea Party in America. Though Blunt also taught drawing, he allowed Hodgkin to paint on sugar paper, using opaque paint. “He had a most beautiful set of rooms in a building called Baldwin Shore, which he decorated with Moorish arches and hung from the ceiling an enormous African carving of a brown-and-white dog with an erect penis,” Hodgkin said. “It was my first contact with the sort of art that was entirely chosen and displayed in order to annoy other people.” Blunt showed his boys works borrowed from the Royal Library at Windsor Castle, thus introducing Hodgkin to Moghul art – he always remembered seeing Mansur’s Chameleon (circa 1600) – and he began collecting Indian miniatures.

Among Hodgkin’s attempts to run away was one in the company of David Lutyens, who was in the same house. He had hoped with the help of the “much older” boy to get to Paris to be a painter. At Victoria Station, Lutyens started worrying about how they would support themselves in Paris, announced “I’m going to call your mother and father” and did so, resulting in their return to Eton. Finally, he was asked not to come back unless he would see a psychiatrist. “The shrink had formed the habit during sessions of sitting fondling himself in his imitation Queen Anne chair while asking his patient if he had any interesting dreams,” he told Toibin. Somehow Hodgkin manipulated him into recommending that he should return to America, and so he embarked on the Queen Mary.

He stayed the summer of 1948 with friends; and in 1949 painted the remarkable Memoirs, in which a woman (his hostess, he told Richard Morphet) is lying on her drawing-room sofa, her head not visible, though her exaggeratedly large hands are, and there is an enormous ring on her right middle finger. A man (a metaphorical analyst?) sits squarely in the middle of the room, listening. The situation of figures in a room in which something telling or erotic is happening, will happen, or even fail to happen – is one that recurred throughout his work. The lines are straight and angular, made with a ruler. This room is carefully detailed, the colours already Hodgkin-ishly bright and contrasting. A later teacher asked him if he was certain he wanted to go to art school, as this painting showed that he had already developed his own artistic language.

The chronology is not clear, but Hodgkin had a single term at Bryanston, where he lived with his house master, before he absconded. There the art master, Charles Handley-Read introduced him to the work of Wyndham Lewis. At some point, he attended a crammer in Wales. “My father by this time was thinking I ought to become a professional artist, but he didn’t have enough money to support me, and was afraid I’d starve,” however, “I had a great ally, Roger Fry’s sister, Margery. She got me into Camberwell, accepted as a special case.” As a child, Hodgkin had often visited the champion of penal reform in her house once or twice a month, with its Omega Workshop painted table that stood on a boldly striped Duncan Grant carpet, near a window overlooking her personal garden that gave onto an even larger enclosed space (this arrangement of spaces was a recurring motif in Hodgkin’s work). He loved her, “because she treated me as a serious person. Nobody else did, much.” Another friend of Hodgkin’s mother, Diana Zvegintzov, who told him that her career was “preparing girls, who ought to know better, for the Civil Service” talked to him once or twice a week about books and films, assuring Hodgkin’s father that “I’ll be his university”.

From autumn 1948 to 1950 he pursued his course at Camberwell School of Art, then dominated by the realist painting techniques of the Euston Road School, which didn’t interest him much, and it was there where he painted Memoirs. He did the conventional course, including life drawing where Quentin Crisp was then posing. I asked him if he was any good at it? “Oh yes, life drawing is just a matter of will power.” From 1950-54 he was at Bath Academy of Art in Corsham, Wiltshire, where he encountered an inspiring teacher of composition in the principal, Clifford Ellis, and made his first print, Acquainted with the Night, inspired by the Robert Frost poem with the slightly different first line: “I have been one acquainted with the night”. Like most promising tyro artists after the Second World War, Hodgkin found that teaching was the best way to support his career, and accepted the post of assistant art master at Charterhouse School in Surrey for the next couple of years. While in that post he married Julia Lane, a fellow student at Corsham, in 1955, and he returned to teach there part time until 1956. The couple lived in Wiltshire and bought a house in west London. They had two sons, Louis, an authority on Lord Nelson, and Sam, a filmmaker.

In these years, despite Ellis’s enthusiasm for the originality of Memoirs, Hodgkin deliberately set about relearning painting, its techniques, and thus enriching his vocabulary, wrote Richard Morphet, “so as to enable each painting, through more flexible, less literal forms ... to contain substantially more”. Morphet says it was not until the late 1950s that he again produced work so personal and intense as Memoirs. In the late Fifties, contemporary American art reached London, with the Abstract Expressionism show (1956) and New American Painting (1959) at the Tate, and solo shows of Jackson Pollock (1958) and Mark Rothko (1961) at Bryan Robertson’s Whitechapel Gallery. In a 1998 interview, Hodgkin said: “It is strange to think that it is possible to paint a picture which is so much bigger than you are, and that’s one of the gifts of the New York school. They taught us that more is more.”

Roger Coleman arranged, in 1962, for Hodgkin to show nine pictures at the Institute of Contemporary Arts, in a two-man show with Allen Jones; and he had his first one-man show at Arthur Tooth & Sons, London. It wasn’t a commercial success, and though Hodgkin actually said (to Edward Lucie-Smith in 1981), “I think I’ve been fortunate in that I wasn’t all successful until I was middle-age, but there were many bitter moments to live through when it was so long before anybody seemed to want to look at my pictures at all.”

All this time Hodgkin was collecting – the occasional Indian miniature, a black bronze vase that came from the Golden Drawing Room at Carlton House, which he bought for £5. In 1959, he met Stuart Cary Welch, an American who, while at Harvard, had begun obsessively collecting Persian and Indian miniatures. Cary and his wife Edith had come to live in London because it had the best public collections of Indian paintings and because there were still good things to be bought cheaply from private collectors. Hodgkin learned a good deal from Welch, both about buying and about connoisseurship, until the day came when he had grown confident enough sometimes to challenge his friend’s judgments. Finally, in 1964, with Robert Skelton, then assistant keeper of the Indian collection in the V&A, Hodgkin travelled to India, the first of the annual trips to the subcontinent he made until his death. The heat and colour of India liberated Hodgkin in the way that its southern-ness must have touched many of his ancestors, and he made many friendships, some with Indian artists. In 1975, however, he contracted amoebic hepatitis, and came too near death for it not to give an edge to his feelings about travelling in India.

While there, though, he assembled much of his world-class collection of Indian paintings and drawings. In later years, he made other astounding collections – French portrait busts, museum-quality furniture, a French Baroque clock, a few choice Western paintings. More than once I’ve seen Hodgkin abruptly break off a conversation, his eye caught by something in the window of a junk or antique shop we were passing, duck into the shop and emerge shortly with a grin, and a parcel containing a Hogarth etching in a particularly fine state, or another treasure overlooked or underpriced by the shopkeeper.

The contrast between his collections and the state of the rooms in which he displayed them was alarming. Bruce Chatwin caught it exactly: “Why, when he never tired of discussing the ultimate refinements of interior decoration, did he take such pains to make his own quarters look like a slum? Why the carefully cultivated damp stains? Why the crumbling plaster, the peeling shreds of wallpaper and the back-breaking chairs? I have come round to the idea that those austere rooms were more affected, more calculated and more dandified than anything I could dream of.” In 1966, Julia, himself, and the boys moved to an old mill house sheltering in a green Wiltshire valley, with crayfish in the stream, peach trees in the greenhouse and, as Bruce says, Hodgkin spent hours rearranging the furniture, especially the weird collection of chairs, achieving “the most tentative effect with the maximum amount of effort”.

Many of Hodgkin’s pictures from this time are portraits. Dancing (1959), with its bands of colour that, in Hodgkin’s words, “bind the painting together, and make it exist from edge to edge”, shows Julia bopping; and he painted artist friends such as Patrick Caulfield, RB Kitaj, Richard Smith, Stephen Buckley, Mick Moon and Robyn Denny (sometimes as couples, though the “Mr and Mrs” paintings mostly date from the late 1960s though to the early 1980s). Tooth gave him another one-man show of 10 new works in 1964, which included the busy Gardening (1963) and Small Japanese Screen (1962-3).

Just as Hodgkin was never a part of any movement or school – despite the adherence of lots of his artist friends at that time to pop art, the situation movement or Kitaj’s School of London – the paintings of this period, though sometimes their figurative origins are still plain to see, defy classification, the marks and shapes often having a formal or compositional function that makes the resulting image neither representational nor abstract. And the marks themselves are evolving into the vocabulary of Hodgkin’s mature work, the blobs and dots with an irregular outline, the straight lines that are now joined by curves, and above all the wonderful bold colours that are the antidote to British drabness.

Teaching part time at Chelsea School of Art from 1966-72, Hodgkin had another solo show in 1967 of Sixteen Recent Paintings at Tooth, but then joined London’s leading gallery of the moment, and in 1969 showed Eight New Paintings at Kasmin Ltd, followed by a show of Nine Recent Paintings in 1971. This year saw his first one-man exhibition abroad, in Cologne, and in 1973 he finally showed in America, at the Kornblee Gallery. It was love at first sight, he told Edward Lucie-Smith: “They realised at once what sort of artist I was when I first showed in New York, I felt I was communicating with an audience. I’ve rarely felt that in England.”

The Hodgkin side of his character asserted itself in 1970, when he accepted an appointment as the artist-trustee on the board of the Tate, a position he relished, and in which he was very active until 1976, when he was given a CBE; and from 1978-85 he made a dynamic, important contribution as a trustee of the National Gallery.

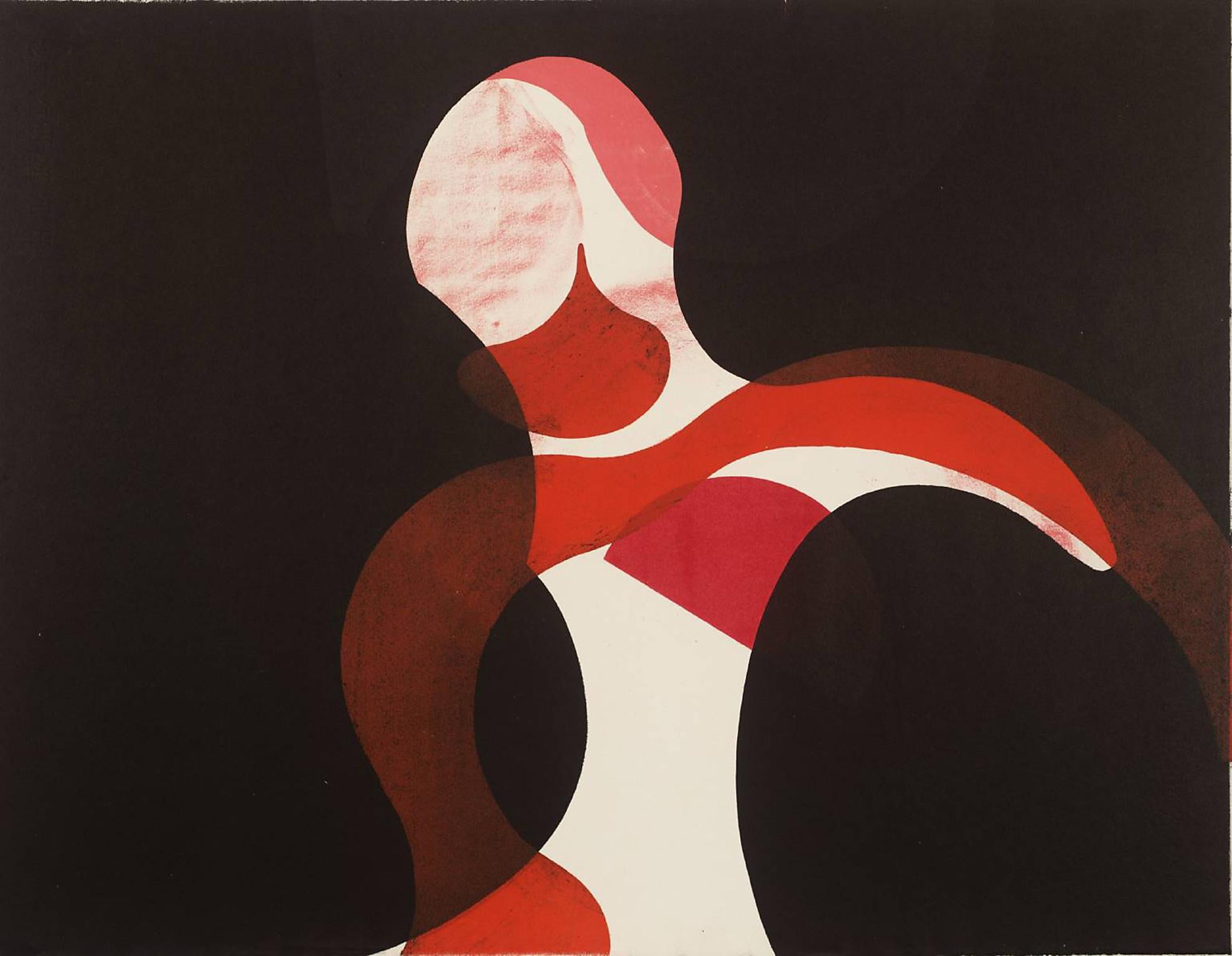

The 1970s were pivotal years for Hodgkin in several ways. He moved to Waddington Galleries, where he showed Nine New Paintings. He took second prize at the tenth John Moores Liverpool Exhibition for the striking Cafeteria at the Grand Palais (1975). He became artist in residence for a year at Brasenose College, Oxford, and he had his first ever retrospective show, Forty-five Paintings 1949-1975, which opened at the Museum of Modern Art, Oxford, whose director was then Nicholas Serota, before travelling to the Serpentine, and four other British galleries. 1977 was a watershed in his development. He made his first hand-coloured prints, and one of these, a coloured etching called Nick, showed the loosening up of form, and of the marks and shapes that would characterise all Hodgkin’s work from this time. It’s a view, through a window into a room, with what looks like a mushroom-shaped table lamp on the right, and bending over it a bulbous pink on white, outlined in black, shape, which is the action-blurred figure of Nick, taking his shirt off. There are the bands of colour – yellow and grey – of that other premonitory work, Dancing, and though the colours are otherwise sombre, dark greens and blue, they are surprising but confidently applied – as is the Hodgkin hallmark.

The loosening up in his work reflected his life. The erotic tinge to some of his work was no longer ambiguous, the tense feeling of desire the viewer senses in Nick is homoerotic, and Hodgkin was bravely coming out to his friends. Though approaching 55, Hodgkin was still slim and cherubic, with his apple red cheeks and blue-grey eyes, and his hair, though grey, was thick and wavy. Howard, who loved a good party, promised that when Penelope Marcus and I married, he’d give us the portrait he was painting of me as a wedding present (which he did).

The National Gallery used to have an annual exhibition called The Artist’s Eye, in which a living artist was asked to rehang pictures from the collection so as to put them in a fresh context. Hodgkin accepted the challenge with alacrity, causing them to clean the neglected fragment of Manet’s The Execution of the Emperor Maximilian and reunite it with the National Gallery’s larger fragment for the first time, in 1979. He designed the installation, which also included a Delacroix, a Renoir, a Tiepolo ceiling, a Velazquez, a Vuillard and two especially fine pictures of his own, the just-finished Dinner at Smith Square (1978-9) and Mr and Mrs EJP (1972-73), on walls painted a pure ultramarine, with banks of red geraniums underneath, “to help people see them better”.

That year he and Peter Blake visited David Hockney in Los Angeles, and Hodgkin kept a journal, in which he recorded various meals and a visit to Disneyland; as a result, he painted DH in Hollywood (1980-84), in which, says Andrew Graham-Dixon in his 1994 Hodgkin monograph, “he turns his subject into a proud erect phallus, a red upstanding penis in the middle of the painting, above a line of blue blobs that reads as the Hockney swimming pool”. He compares this to Paul Levy (1976-80), with its “pasty smear of pink with smudged eyes and mouth, surrounded by thick blobs and blotches of paint the colour of confectioner’s custard”, a “gently mocking, affectionate monument to gluttony, its pleasures and consequences”. Whereas the Hockney is “an image of social and sexual pleasure, of conviviality as a form of exuberant performance.” The visit also resulted in Peter Blake’s take on Bonjour M Courbet, The Meeting or Have a Nice Day, Mr Hockney (1981-83), with portraits of all three celebrated British painters.

Hodgkin loved and knew a great deal about the performing arts. In 1981, he designed the sets and costumes for Night Music, choreographed by Richard Alston for Ballet Rambert, for whom he also did Pulcinella in 1987. The next year he did Piano, choreographed by Ashley Page for the Royal Ballet. In 1997, he did his first design for Mark Morris, the backcloth for Rhymes with Silver, then for Kolam in 2002, and for Mozart Dances (2007), and their last collaboration was in 2016. He designed another backcloth in 1999 for Holst’s opera, Savitri, staged at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington DC, and again at Aldeburgh in 2002.

Hodgkin’s work was increasing in price; he was taken up by the dynamic dealer Larry Rubin, and his next show in New York was at Knoedler gallery in 1981, where he showed 12 pictures. Lawrence Gowing wrote in the catalogue: “Absorbed in the simultaneous flat-and-deep of Hodgkin’s colour one no longer seeks to decode it. One dwells in it for itself; in its presence, one is in its company.” Critics had always praised Hodgkin as a colourist, but these pictures, which included In a French Restaurant (1977-79) with its saturated tricoleur superimposed on hot reds and pinks, and the two bold swathes of red paint at the bottom of Red Bermudas (1978-80) that read as Hodgkin’s close friend Terence McInerney’s Bermuda shorts. McInerney is a dealer in Indian art. The emotional resonance of both these paintings make it clear to the viewer that these recollect “experiences of one sort or another”, Hodgkin told Lucie-Smith. He went on to say that someone once said to him: “‘You must have to live like a novelist to paint pictures like this.’ Which is true.” Later that year, Portraits of Terence McInerney I and II were exhibited in the Royal Academy’s show A New Spirit in Painting. Hodgkin was very aware of his own oblique position in the artistic fashion parade mounted in this show. He later (in 1998) said of the show and its title that painting remained alive in a way that “when I was young, would have seemed ridiculous. ‘Pompier’ painting, as it was called, has come back with a bang – huge subject pictures … the old spirit of painting – pictures that would have made Cézanne and the post-impressionists turn in their graves. Enormous subject pictures which, as physical objects, were often produced in the most perfunctory manner possible, that were big and … in your face, comparable to these huge machines in the Paris Salons, which I was brought up – I think quite rightly – to despise”.

Hodgkin’s interest in Indian art extended to contemporary painting, and in 1982 he curated an exhibition at the Tate of Six Indian Painters, who included his friends Jamini Roy and Bhupen Khakhar, which was followed by a show there of his own work, Indian Leaves, 15 pairs of images made by staining colour directly onto wet, freshly handmade paper. He made them while staying in Ahmadabad, with the Sarabhai family in the villa Le Corbusier had built for Manorama Sarabhai in 1951. Bruce Chatwin wrote an essay in the catalogue that alluded to Hodgkin’s coming out as gay. He showed again at Knoedler in New York, 15 paintings that revealed his new, freer style. “Gone were the portraits of forlorn married couples in rooms,” Chatwin wrote. “To be replaced by a new kind of subject and a new mood. In his most recent pictures, the sitters – though they still exist under layers of paint – are overwhelmed be dots, splotches, flashes and slabs of colour, recording situations or impressions that Howard, in his new persona, has witnessed. Some are simple enough: it doesn’t require much imagination to see that Red Bermudas is of a sunbather in Central Park. But who would guess that Tea, a panel over-splattered in scarlet, represents a seedy flat in Paddington where a hustler is telling the story of his life?”

The next year McInerney and Hodgkin chose 16th to 19th century Indian Drawings for an exhibition at the Hayward Gallery, and in 1984, Hodgkin had the exhibition that set the seal upon his artistic stature. He was chosen to represent Britain at the XLI Venice Biennale with 24 paintings, shown in the British pavilion, whose interior he had redecorated his then-favourite eau de nil. The show was the highlight of the Biennale for many visitors, and confirmed the practice that was repeated for each of Hodgkin’s major shows from then on, in which he was accompanied by a large entourage of family and friends, and treated to a succession of glamorous, generous parties given by his various dealers. The group included both Julia and the young man with whom Hodgkin was to share the rest of his life, Antony Peattie, an opera professional, then working in Cardiff with the Welsh National Opera. Later this year the Venice show was augmented to become a large, partial retrospective, Forty Paintings, travelling first to the Phillips Collection in Washington DC, then to the Yale Centre for British Art, to Hanover in Germany, and finally reopening the refurbished Whitechapel Gallery in London. In a catalogue interview with the late David Sylvester (whom Hodgkin came to rely upon to help hang his shows), he said: “To be an honest artist now, you have to make your own language, and for me that has taken a very long time.” He also designed one of Four Rooms featured in an Arts Council touring exhibition, for which he created fabrics and lamps. He was the subject of a BBC television Arena documentary made by Nigel Finch; and showed a dozen paintings at Knoedler, New York.

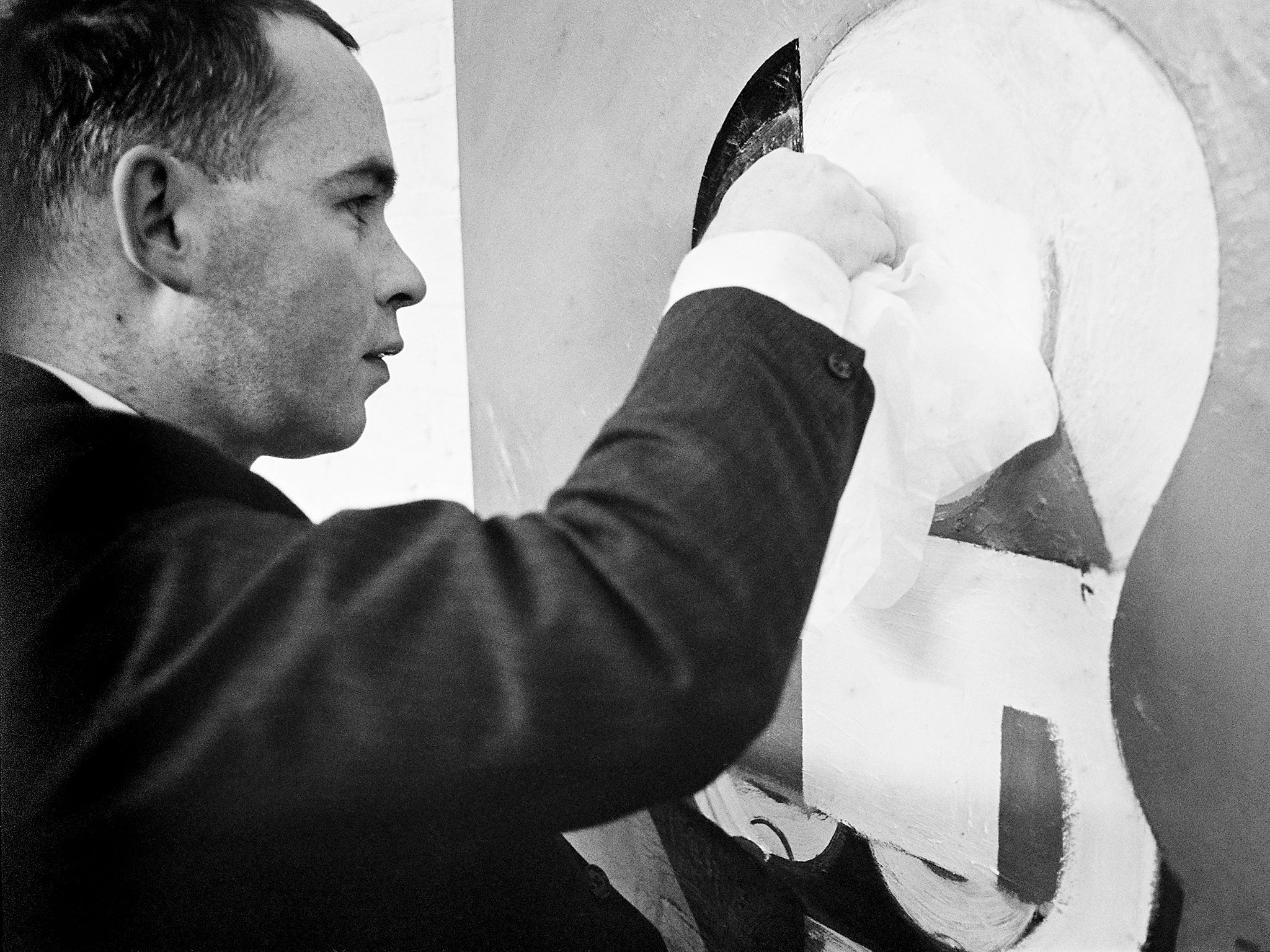

Hodgkin had hit his artistic stride. In 1985, he won the second Turner Prize (though he should surely have won the first, the year before), and the Tate showed 25 of his prints; the British Council toured a print show to ten countries from now until 1990. He continued to show at Knoedler, but at home began to show with Leslie Waddington. It was characteristic of the pictures he exhibited now that the dates show that he was working on them for a period of years. In the Georgian house he shared with Peattie near the British Museum, he had a large studio off the courtyard. Against its white walls stood or hung dozens of the wood surfaces on which he almost exclusively painted. Lightweight unbleached muslin stretched screens could be placed in front of the hanging pictures, so that only one image could be seen at a time. His pictures needed space, lots of it; even the tiny ones could hold an entire wall in a good-sized gallery; and this was always an issue when installing his exhibitions. He sometimes felt that some of his pictures “killed” those in the same room, unless great care was taken.

The late 1980s and the 1990s was a period of grief, as friends died of Aids, Nick Underwood first, then Chatwin in 1989, then Donald Richards, the Australian stockbroker, and Donald’s ex-lover, Sebastian Walker, in 1991. This was the tip of a very nasty iceberg, and Hodgkin’s tears flowed often. But this was also the time when new, deep friendships were made. Susan Sontag came as a splendid package with her girlfriend, the photographer, Annie Liebowitz, the dancer Mark Morris and other lustrous New Yorkers; Julian Barnes and his wife the late Pat Kavanagh became regular travelling companions. James Fenton, the poet, former war correspondent, extraordinary gardener, is also a connoisseur of the visual and plastic arts, and Hodgkin loved talking and visiting salerooms with him. Fenton’s partner Darryl Pinckney was embraced by Hodgkin’s friendship; as were long-time friends such as Caroline Conran, and Michael Seifert, who acted as his lawyer. For a time, when he was unpartnered, Hodgkin, Seifert, and I dined together once a week, and called ourselves the Wednesday Club; Peattie, who was soon to publish The Private Life of Lord Byron and was co-editor with Lord Harewood, revising Kobbé’s Complete Book of Opera (1997), became the fourth member. Hodgkin was a generous friend; he made hand-coloured graphics for books by Sontag, Barnes and Peattie, and dust-jacket art for me and several others.

Hodgkin’s own collection of Indian Paintings and Drawings was first shown in 1991 at the Sackler Gallery of the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, then at the Ashmolean, Oxford, the Rietberg, Zurich, the British Museum and the Museo di Castelvecchio, Verona. The art world was not then so alert to the need for sound provenance for all works of art, and as all these works had been bought even earlier, some of Hodgkin’s pictures were without sufficient provenance. Much of the collection is on display at the Ashmolean. In 1992, he designed a mural for the new British Council headquarters in India. The building in New Delhi is by the celebrated architect Charles Correa, and its façade incorporates Hodgkin’s design in black stone and white marble that evokes the shadow cast by an enormous tree.

He changed dealers again in 1993, now showing 24 pictures with Anthony D’Offay; and in 1995, had his first graphics show with Alan Cristea of his large Venetian Views. This year and the next he was the toast of America, with the rare honour for a living British artist of having a show at the Metropolitan Museum, New York of 38 works in Paintings 1975-1995, which travelled to Fort Worth, Düsseldorf and the London Hayward, where he had all the internal walls removed, and the remainder painted “mailbag grey”. He showed in Zurich with Larry Rubin in 1997, and the next year on Madison Avenue with his new American dealer, Larry Gagosian, followed by his next London show, a large one of 22 works, with D’Offay.

He was always keen on unusual commissions, as when he designed a 25m glass mosaic mural for the Broadgate swimming pool in London, and an image that was enlarged photographically to cover the outside wall of the circular London Imax cinema on Waterloo roundabout in 1999. He designed the 64p millennium stamp for the Royal Mail in the same year. In 2000, for the National Gallery’s Encounters show he ambitiously exhibited his own version of Seurat’s Bathers at Asnières next to the original, and the next year repeated the gesture at the Dulwich Picture Gallery.

To celebrate Hodgkin’s 70th birthday the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art (the Dean Gallery) showed 20 of his works in Large Paintings 1984-2002 in two rooms painted ultramarine and linked by a bridge. The next year saw the publication of a catalogue raisonné of his prints, and a big show at the Downtown Gagosian in Chelsea of 38 new paintings, most of which went on, in 2004, to Gagosian in Los Angeles. In 2006, a very large retrospective opened in Dublin at the Irish Museum of Modern Art, and toured to Tate Britain and to the Reina Sofia, Madrid; and that year saw the second edition of Marla Price’s catalogue raisonné of the paintings. In 2009, he showed As Time Goes By, a pair of monumental prints, at Alan Cristea – they were technically virtuoso works, and thought to be the largest etchings ever made. Hodgkin returned to Modern Art Oxford in 2010, with a large retrospective.

Hodgkin accepted a knighthood in the New Year’s Honours list for 1992, and regretted it almost immediately – having previously been of the opinion that artists should disdain such worldly baubles. He rarely used the title, but after 10 or 15 years had passed, stopped wincing when he was referred to as “Sir Howard”. Honours continued to rain down upon him nevertheless, as in 1997 when he was awarded the substantial Shakespeare Prize by a German foundation. (His predecessors included Ralph Vaughan Williams, Dame Janet Baker, Graham Greene, Philip Larkin, and his friends David Hockney and Julian Barnes; this annual prize given to a British artist or performer ended in 2006.) In the New Year’s Honours list for 2003, Hodgkin was made a Companion of Honour, an appropriate award he was very happy to accept. He also held an honorary doctor of letters from the University of London (1985), and of Oxford (2000); in 1988 he was appointed an honorary fellow of Brasenose College. In 2009, he entered into a civil partnership with Antony Peattie.

Howard Hodgkin’s position in the history of art is secure. Though he was aware of, and often acknowledged his debt to past artists, he was a complete original, in his subject matter – though it was always remembered experiences, in his use of colour, and in the visual language that was his alone. He was also a remarkable human being – there is no hyperbole in calling him a genius. And he also had a genius for friendship: he lived by the Bloomsbury credo that the highest goods are the twin pleasures derived from the appreciation and making of works of art, and personal relations. I regarded him as one of my best friends. I am sure I am not the only one who turned to him for, and took his advice in times of crisis; and I know I am not the only friend to whom he gave a picture and then urged him to sell it in time of need. His love was as generous as his art.

Paul Levy, the subject of two Hodgkin portraits, and Dame Margaret Drabble will have a conversation about Hodgkin’s portraits at the National Portrait Gallery on 13 April

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments