How do award-winning artists spend their prize money?

As one of Britain's biggest arts prizes is handed out for a 20th year, Holly Williams hears how five previous recipients have used their £50,000 windfall – from giving up the day job to, um, buying a mobile disco

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The modern artist faces a conundrum: good work needs time and space, imaginative and physical. But making work also costs money; studios and materials don't come cheap, and even aesthetes have to eat. So you get a job that pays … then you don't have the time – or headspace – to make the work.

We hear about the super-successful celebrity artists who make a fortune – but they are the minority. For emerging artists, making work and making ends meet is rarely easy. Which is why, since 1994, the Paul Hamlyn Foundation, without fuss, has been making substantial awards to British artists.

Hamlyn, a publisher and philanthropist, died in 2001, but the work of encouraging new talent went on and, in 2007, the remit was widened to include three composers as well as five visual artists. Each beneficiary receives a sum of £50,000 over three years. But the real boon is that there are no conditions attached: the artists are free to spend it as they like.

Industry experts put forward names and a panel of five judges looks – in the first instance anonymously – at the artists' and composers' previous work. Unusually, the next round takes into consideration need, as well as raw talent and future potential, with nominees submitting short statements on how they would benefit from the award.

This year's recipients have just been announced – congratulations to visual artists Bonnie Camplin, Michael Dean, Rosalind Nashashibi, Katrina Palmer and James Richards; and composers Martin Green, Shabaka Hutchings and Pat Thomas. And a quick glance through previous lists shows that the foundation – set up by Hamlyn in 1987 to encourage participation in the arts – could help them on to bigger things: many recipients have gone on to be highly acclaimed, including the Turner Prize-winning conceptual artists Jeremy Deller and Simon Starling, the film-maker Clio Barnard, the YBA Michael Landy, the folk musician Eliza Carthy and the contemporary classical composer Tansy Davies.

For many, the sudden arrival of 50 grand had a predictably transformational effect, allowing day jobs to be ditched, world-class instruments to be purchased, studio rent paid or simply providing creative time and space. So how might this year's recipients use their windfall? We asked five previous winners to share the wisdom of their experiences. k

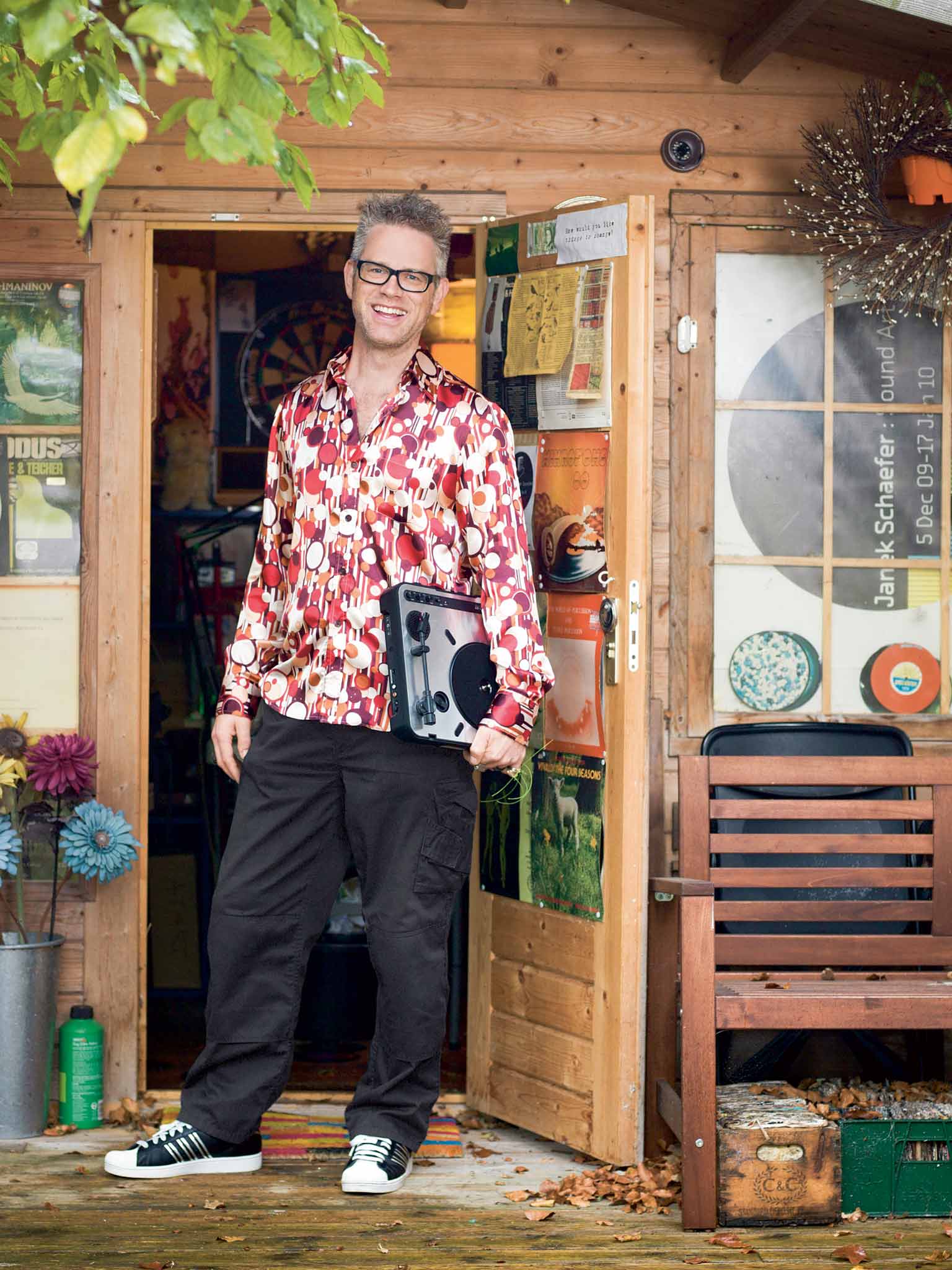

Janek Schaefer: Composer and sound artist, 44, winner in 2008

"I bought myself a public-address system, and transformed it into a disco, which now provides half my income. I play on the edge of the dance floor, with a table covered in a red spotty cloth, a laser, lights, a couple of speakers, a big smile and a can of glitter. I'm not a club DJ or a mobile DJ – I'm a party DJ.

"My daughter was two at the time and when I played a record, she'd wiggle. I wanted to buy her the best dance music from the whole of history. So, with the money, I also bought a retired pub DJ's old seven-inches.

"I'd moved to Walton-on-Thames and I started doing public parties for under-sevens. As an avant-garde artist, most people find what I do a little odd, but with the disco, the more bonkers I am, the more people think I'm wonderful. Six years on, it's going very well: I just played to 7,500 people in Portugal, and I do weddings.

"It took me some time to be able to talk to the art-music community about being a DJ, but I've become proud of it.

"It's begun to seep into my artwork – in my most recent show, I sprinkled circular frames with different shades and grades of glitter to make starry, earthy planets. It's my interpretation of a disco ball in an arty context.

"I got the award a month or two after that crash and funding disappeared; the education establishment didn't even have any money for lectures. I've diversified beyond belief. As well as the disco, I'm a handyman, a visiting professor at Oxford Brookes, a concert performer… and I still can't make the national average wage. God, it's hard."

Phyllida Barlow: Installation artist, 70, winner in 2007

"I wanted to be able to employ assistants, so I could fulfil my love of making large work that reaches into all parts of a space. I’ve made that kind of work since the 1970s, but I was having a lot of problems with my joints, which made it physically too difficult for me.

"Being able to employ two to four assistants was a huge step up; they became an extension of myself. I don’t mean that in an arrogant way, but I could direct – physically – how I wanted the work to be. Some works went up to 6m by 15m wide. For me, there was a very revitalised ambition.

"Making work is expensive; you need mental, physical, psychological and imaginative space. You get jobs and they provide an income but they also disrupt your [artistic] intentions. It’s an ongoing struggle at every stage of an artist’s life, and it’s never really properly discussed: how do you balance working for money (in my case through teaching), your family – I have five children – and your work?

"I was able to climb the academic ladder and secure a reasonable income, but the demands are increasingly heavy. When I got the award, there was an opportunity to go part-time.

"Also, the studio roof was in a terrible state, leaking badly, and I was able to get it repaired. It was so liberating, being able to work in the space very freely, rather than dodging buckets of water."

Yinka Shonibare: Artist, 53, winner in 1998

"Winning the award was very useful to help me buy materials for my art: I use fairly expensive fabrics. I'd buy [colourful patterned cloth] from Brixton Market; it was about £40 for 12m.

"I am of Nigerian origin, and it was a time when there was a lot of debate about artists' identity. I had produced quite political work at college, about perestroika in Russia, and a tutor said, 'Well, this work isn't authentic African art, is it?' So I started to ask questions about authenticity.

"Then I realised those fabrics aren't authentic African textiles at all, but Indonesian-influenced, produced in Manchester, and sold to West African markets. So I would do things like make them into Victorian costumes, looking back at the colonial relationship between Nigeria and the UK. The money helped me push the boundaries of my practice, to produce more complex works.

"I also had a part-time job at a charity called Shape, making the arts accessible. I was near to being promoted, but if I took on more responsibility to get more money, that would mean I wouldn't have time to do my art. So I was at a crossroads: it was really quite a difficult decision. And the award made that decision very clear: I would give up the day job and focus on art.

"I was able to push my projects even further, which meant, within a couple of years, I was financially independent, from the sales of my work. And by producing more work I was able to afford to buy my studio in east London. So the award also helped me get on to the property ladder."

Ryan Gander: Conceptual artist, 38, winner in 2007

"The award let me take a year off on sabbatical, and I employed somebody to sort out the studio. A tidy studio is a tidy mind!

"I had been a bit hand-to-mouth: I was making work really quickly and didn't have time to reflect on it. So the award bought me time. I didn't suffer from panic attacks any more – I'd been so stressed out about having to deliver, deliver, deliver.

"I gave up teaching for a year: I had been teaching in Manchester, London, Sheffield and Leeds, five days a week, then I'd have Sundays in the studio.

"I spent the year just collecting ideas. I travelled a lot – Italy, the South of France, Los Angeles – and filled notebooks, and when I came back I didn't have that panic any more that every work was going to be my last. It gave me the time to develop my own language rather than be madly boshing stuff out. Visual language is a language like any other, with the same nuances and articulations – it takes time. I am who I am because of that year.

"We're in a really critical time for the trajectory of art history, with [cuts to] funding for art schools and the gentrification of the art world. There's less and less room for artists who don't have a trust fund, who are usually – to be honest – the ones with better creative minds, more integrity and keener ambitions. It's a very rocky moment."

Iain Ballamy: Jazz composer and saxophonist, 50, winner in 2007

"The lasting totem [I have from the award] – and I do think of it as a totem – is my beautiful Yamaha S6 grand piano. The really amazing thing about the award is it's without conditions; I could have gone and bought a silly car, but I bought a silly piano instead!

"Every single note you play on it sounds lovely – even really simple things have so much depth and beauty. I use it for writing especially; I sit up at night playing it. I can't leave it alone – it attracts you to work.

"It's always difficult finding time to compose; you have to have inspiration but you do also have to just knuckle down and work. It's hard to say no to work that pays. Most everybody I know needs the money. As a musician, composer, educator, you make a living by performing, doing workshops, writing music commissions… I wouldn't have said it's an easy option. To get a year or two off from that was just brilliant.

"I was asked to write a piece for the London Sinfonietta that premiered at Kings Place and on Radio 3 – that was a big commission, challenging and out of my comfort zone. The award gave me confidence, and the time and space to do that; it was definitely massively enabling.

"It's not just the money. It was a real honour: a life-affirming compliment, to be noticed and chosen. It gave me confidence to take on bigger writing projects; if other people felt I could do it, then I jolly well could!"

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments