Henri Matisse and the nun: Why did the artist create a masterpiece for Sister Jacques-Marie?

Henri Matisse’s greatest masterpiece resides not in a gallery, but on a peaceful hillside near Nice: a chapel he designed in gratitude to the nun who helped him through a troubled convalescence

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Famous as a great colourist, towards the end of his life, the artist Henri Matisse moved from painting towards a new art form: cut-outs. He likened the process to sculpture – "carving" into colour – as he sliced into huge sheets of vividly painted paper before pinning the shapes in place on a canvas. This novel approach – which produced some of the most recognisable pieces of art from the 20th century, such as his Blue Nudes, Icarus and The Snail – is being celebrated in a major new exhibition at Tate Modern, in conjunction with New York's Museum of Modern Art.

Yet it wasn't any of those works that Matisse himself termed his "masterpiece": that honour he bestowed on the Rosaire Chapel in Vence, in the south of France. He worked on it for four years, from 1947 to 1951, designing the building, the stunning stained-glass windows, the tiles with monochrome religious imagery on the walls, even the zany chasubles (vestments) the priests wear. Still a place of active worship for Dominican nuns today, it was an ambitious challenge for Matisse, who was no architect, and was very unwell at the time – and he considered it "the achievement of an entire life's work, the outcome of tremendous, difficult, sincere work".

It might have been the pinnacle of his career, but the Vence Chapel was also a way for Matisse to use his talents to produce a heartfelt gift for a Dominican nun named Sister Jacques-Marie.

As a young woman and student nurse, then going by the name of Monique Bourgeois, she had cared for Matisse after a gruesomely botched operation for intestinal cancer in 1941, from which he was never to fully recover. Yet it was being confined to his bed as a physical invalid that in part led to his new cut-out technique – and he would never forget the kindness of his nurse.

He immortalised her in several paintings at the time, and their friendship endured – although she later quashed rumours that their affection might have strayed into the romantic, saying in an interview in Paris Match in 1992: "I never really noticed whether he was in love with me… I was a little like his granddaughter or his muse."

Some years after nursing Matisse, in 1946, Bourgeois wrote to him to say she was becoming a nun. The Dominican sisters settled in Vence – coincidentally, very close to Villa Le Rêve, where Matisse was living. In one of their many conversations, she mentioned to Matisse her desire for a chapel for the sisters on this pretty hillside. Initially, the artist offered to help design the windows, but soon he was involved in the whole building, right down to the candlesticks (modelled to look like long-stemmed anemone flowers). He worked alongside Brother Rayssiguier, who oversaw the construction of the chapel and was far-sightedly enthusiastic about getting such a well-known artist involved. Rayssiguier thought a splash of modern art might help bring the church's appeal up to date.

Matisse, however, was less concerned with the revival of Christian art than with a personal sense of the spiritual – and the creative challenge such a building would present to him. "He wasn't religious – he was raised Catholic but was not practising," explains Flavia Frigeri, assistant curator of the Tate show, which features sketches, maquettes and photographs from the Vence Chapel. It was more the chance to create a whole building, she suggests, than any particular Catholic calling.

However, the chapel has been a place of worship since it was unveiled in 1951, and – although modest and small – it is charged with a serene beauty that can be spiritually affecting to not only the nuns who pray there today, but to visiting art lovers and tourists. Even stepping foot inside in January, as I did, with a weak sunlight coming through his gorgeous "Tree of Life" stained-glass window, you feel enveloped in pure colour that is both revivifying and calming. The vibrant hues – "ultramarine blue, bottle green, lemon yellow", to use Matisse's labels – are reflected in and dappled across the polished pale marble floor and white walls. His imagery, though typically abstract, draws inspiration from the natural world, making it emotionally accessible to all, not just those steeped in scripture.

"The spiritual expression of their colour strikes me as unquestionable," wrote Matisse of his leaf patterns in 1951. "Simple colours can affect innermost feelings, their impact being all the more forceful through their simplicity. Blue… affects feeling like a vigorous stroke of a gong."

The Vence Chapel stands apart from archetypal Catholic iconography – even the images of Christ are abstracted into pure line, while an image of the Virgin Mary and child comes surrounded by almost hippyish flowers. It's a far cry from the gruesomely realistic emaciated crucifixion imagery often associated with Catholicism. Yet Sister Marie-Pierre, a Dominican nun, echoes Matisse's sentiments when I ask how it feels to worship in the chapel. In broken English, a thick French accent and a beaming smile as radiant as the buttercup-yellow light filling the room, she says: "We worship in beauty, instead of in bad things. It feels special. And I think it is better to pray in beauty."

She leads us through the 14 images that make up "Stations of the Cross", a series of rather furious-looking paintings on the back wall, which are complemented by enormous but simple outlines of Saint Dominic and the Virgin and Child on two other walls. The latter, Matisse wrote, "have a tranquil reverent nature all their own" while the "Stations of the Cross" are "tempestuous". All three were painted in bold, sweeping black on white enamelled terracotta tiles.

The process wasn't simple, however. In those four years of preparing the chapel, Matisse would practise his designs on paper, over and over again. From initial early studies of religious art by Rubens, Dürer and Mantegna, he developed his own iconography. "There were many images as he worked it out; he simplified, intensified, condensed," suggests Nick Cullinan, co-curator of the Tate show alongside Nicholas Serota. And Matisse's pious muse, Sister Jacques-Marie, continued to discuss the different designs with him, their affectionate friendship allowing her to be free with her opinions; Matisse later described the chapel as their "shared project".

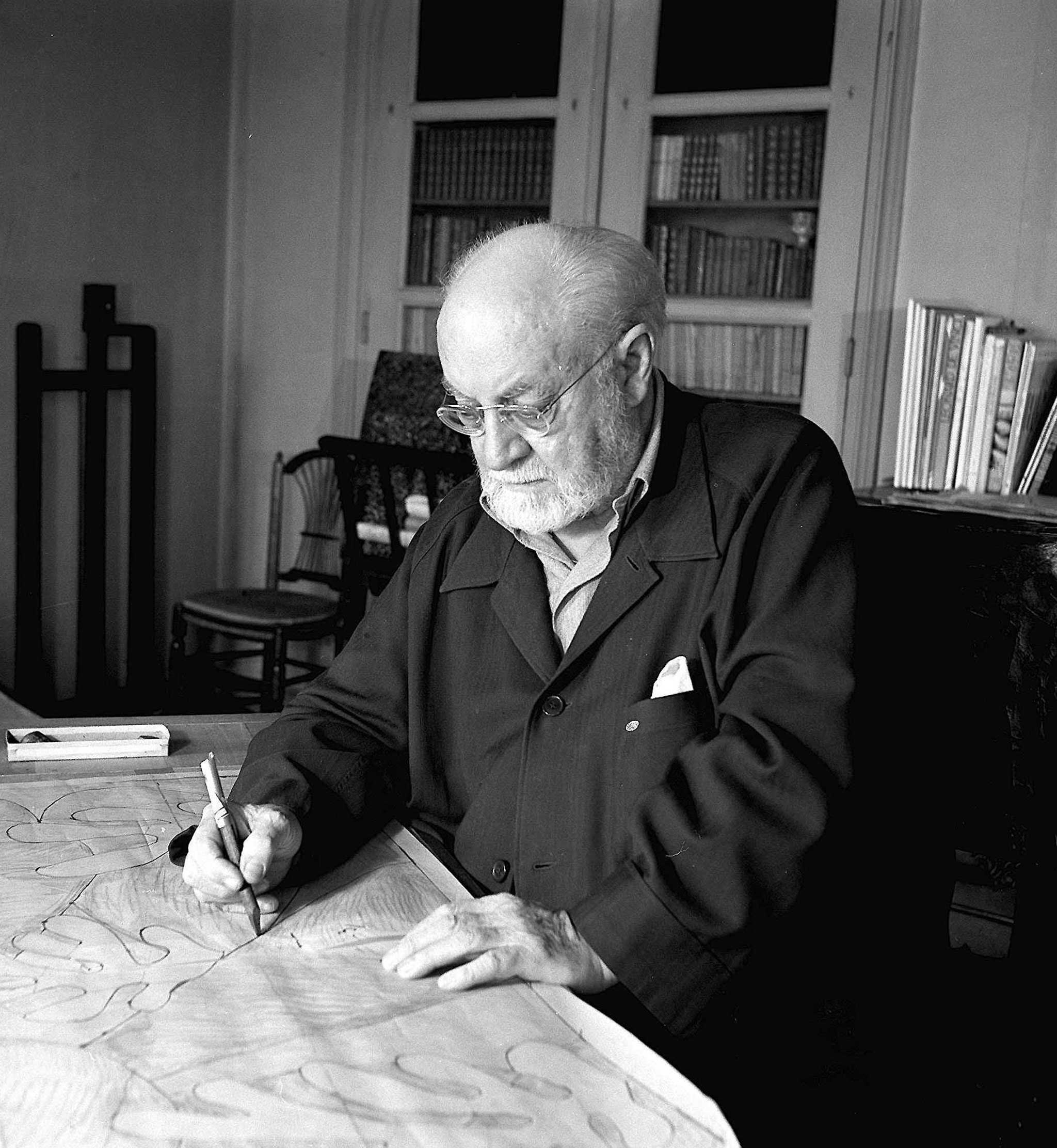

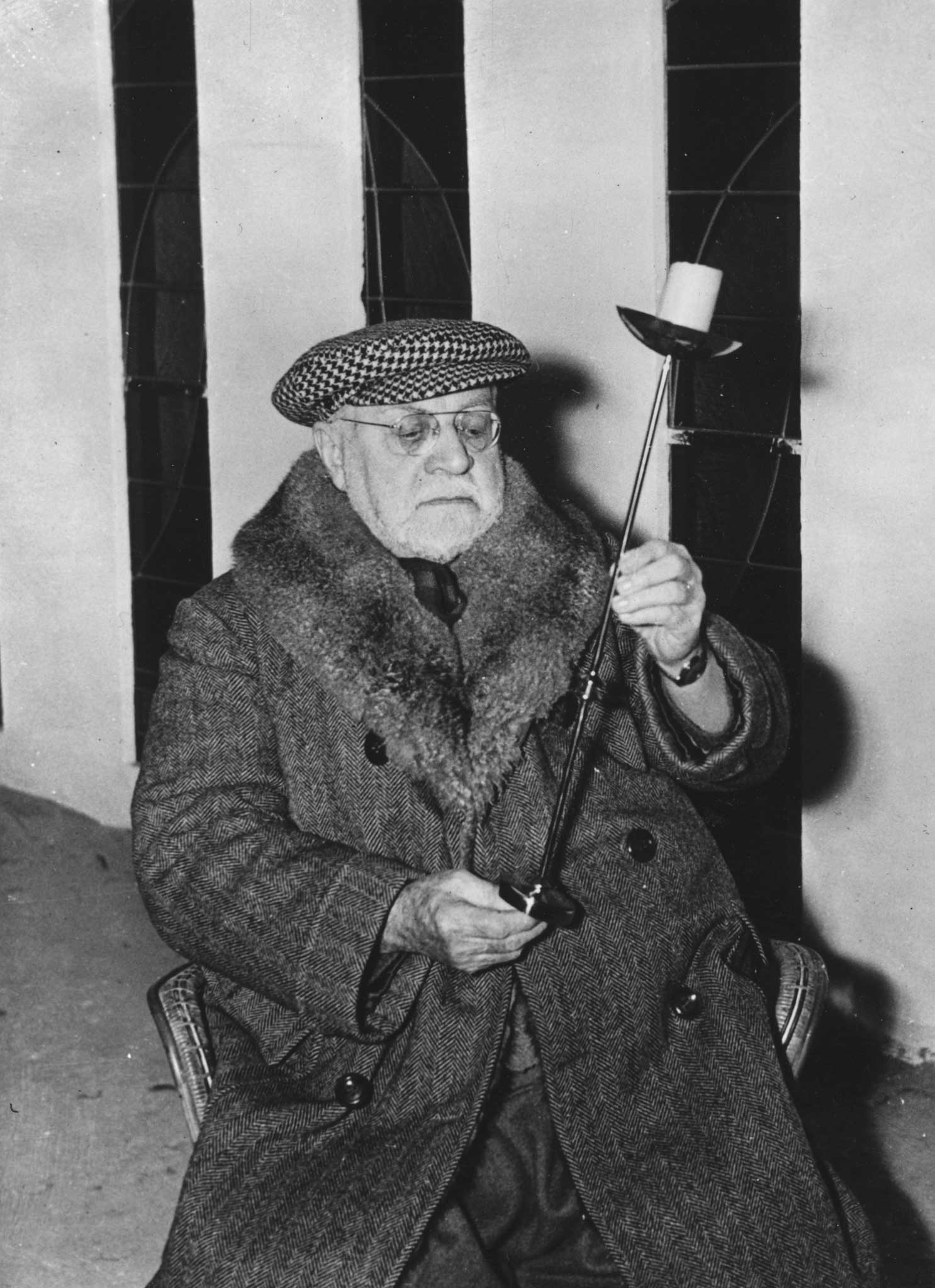

The images he worked on were several metres tall, and required fluid, long lines drawn in one smooth motion, so Matisse would practise using a charcoal stick at the end of a bamboo wand about two metres long, allowing him to reach. In his seventies while working on the chapel, and unable to stand for any length of time, this long "wand" had the added advantage of letting him practise from a chair or in bed. He was known to even paint on the ceiling if he woke up, restless, in the middle of the night.

And so it was that the chapel came to life around him. Matisse was now working in his apartment in the grand old Hotel Regina, in nearby Nice. Long rolls of paper cascaded down the walls for him to paint and draw on with his k stick, while he perfected the stained-glass windows using his cut-out technique: snipping out the brightly coloured plant shapes and pinning them to his walls. Photographs reveal how the artist even mocked up an altar in the middle of his room, using boxes, chairs and a table. He spent nearly two years in this work-in-progress world, inside his studio, inside his apartment; "He really lived in it," says Frigeri.

Eventually, Matisse had practised the outline of his figures so often, he was able to draw them blindfolded. Appropriately, the artistic experience became almost divine: he commented that all the studies "enable the painter to give free reign to his subconscious… after a certain point, it is no longer up to me, it is a revelation: all I do is give myself up."

And so by April 1949, Matisse was ready to paint on to the tiles which would be mounted on the chapel's walls. He did not sign the works – they were to be viewed as integral parts of a religious building, not as collectible pieces. "They were not designs, but signs – to help praying," says Sister Marie-Pierre. Matisse was, she insists, quite adamant that the Vence Chapel should "never become a museum".

Matisse kept his hand in even until the final finishing touches: he designed the pews and altar, set at a jaunty angle and made of pierre de Rogne stone he specially selected because its pale-brown grain made it look like "a piece of bread", according to Sister Marie-Pierre. Most fun, however, are the chasubles that the priests still wear – Matisse made several designs for different Holy Days. Some are gloriously bonkers, with bold patterns – very much in his late style, mimicking the cut-outs in cloth – of flowers, leaves and starbursts, as well as abstracted crosses and crowns of thorns. The eye-popping colour schemes throw together lime, yellow and black or lilac, green and rose, and would look as at home on the cover of Sgt Pepper's as swishing through the Vence Chapel. They were hailed by Picasso as the best bit of the whole project.

The chapel was consecrated on 25 June 1951; thousands of locals and visitors turned up, but sadly Matisse was too unwell to attend. The chapel soon attracted great international attention. Matisse's cut-outs had not always been viewed in a positive light by the art establishment – there was a sniffy sense, initially, that they were inferior to paintings, suitable for magazine covers but not for art galleries. But the chapel was recognised immediately as a significant work: "With the cut-outs, people express misgivings, that the old man's past his best; but the stained glass – that's fine, that's well-received," explains Cullinan. Time, Paris Match, and Vogue all reported on the chapel with delight, the latter dubbing it a "Church Full of Joy".

It's an apt phrase for the building. But the chapel also had a significant impact on the final years of Matisse's artistic career: his subsequent cut-outs, until his death in 1954, went super-sized, growing to a scale similar to his preparations for the chapel, taking over whole walls. And for Matisse, there can be no doubt about the importance of the chapel: although unable to be there at its unveiling, he sent along a written statement. It read: "This work… is the result of all my active life. Despite all its imperfections I consider it as my masterpiece."

Henri Matisse: The Cut-Outs is at Tate Modern, London SE1, from 17 April to 7 September

A cut above: Matisse's late flowering

Born in 1869, Matisse qualified in law before studying art in Paris. As a painter, he was influenced by Impressionism, before developing his own style – using brilliant swathes of colour – that was dubbed Fauvism. He later also experimented in Cubism.

The cut-outs were a major development towards the end of his life. They began for practical reasons: with commissions for the Ballet Russes in 1939 and for the covers of magazines such as the art and literature review 'Verve'. These were followed by an artist's book, 'Jazz', featuring the well-known image of Icarus in 1947.

To make the cut-outs, Matisse had his assistants paint sheets of paper in bold, luminous colours; using large shearing scissors, he would cut into the sheets and pin the cut-out shapes first to his walls to perfect the look, and then permanently to canvas.

The technique prompted renewed interest in the human form; but as well as a solidity and stillness, the technique also offered a sense of vivacity and movement.

Matisse was prolific in his final years, despite ill health, and the cut-outs grew in scale. 'The Snail', one of the most famous, epitomises his large-scale, bright, abstract approach.

Matisse also used them as trial-run maquettes for large-scale ceramic commissions. In 1952, Sidney and Frances Lasker Brody asked him to create an outdoor tiled mural for their LA house – it took him four attempts to satisfy them, the final result being 'The Sheaf', which features his favourite wobbly-leaf designs seen in Vence.

The cut-outs were initially met with dismissive bemusement, seen more as decorative than fine art; but by the late 1950s, the art world had recognised them as significant achievements, and Matisse's bold use of colour and shape has influenced everything from abstract art to fashion to graphic design ever since.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments