Henri Cartier-Bresson: Right on the button

Henri Cartier-Bresson never thought what he did was art, but he was wrong, says his one-time colleague Adrian Hamilton

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The more you see the photographs of Henri Cartier-Bresson the stronger becomes his claim to be the greatest photographer of the previous century.

There are more arty photographers such as Edward Weston and Richard Avedon. There are photographers such as Robert Capa and Donald McCullin who have recorded better the face of war and the tragedies of the age. But Cartier-Bresson makes you see the world anew. You can never see one of his pictures without being surprised at their quirkiness, their freshness and, above all, their humanity.

It is 10 years now since his death and the Pompidou Centre is marking it with, almost unbelievably, the first full retrospective in Europe. It aims – and largely succeeds – in trying to break down what it is that makes him such a great photographer and to show just how diverse and developing was his art.

It’s not an approach that the photographer himself would necessarily have liked. His ambition was always to produce an art that was artless. Photography was never a competitor or a branch of “Art” in his eyes. It was something special to itself, a means of capturing what he famously called the “decisive moment”, when the balance of a composition or the look on a face said something special about time, place and the world we live in.

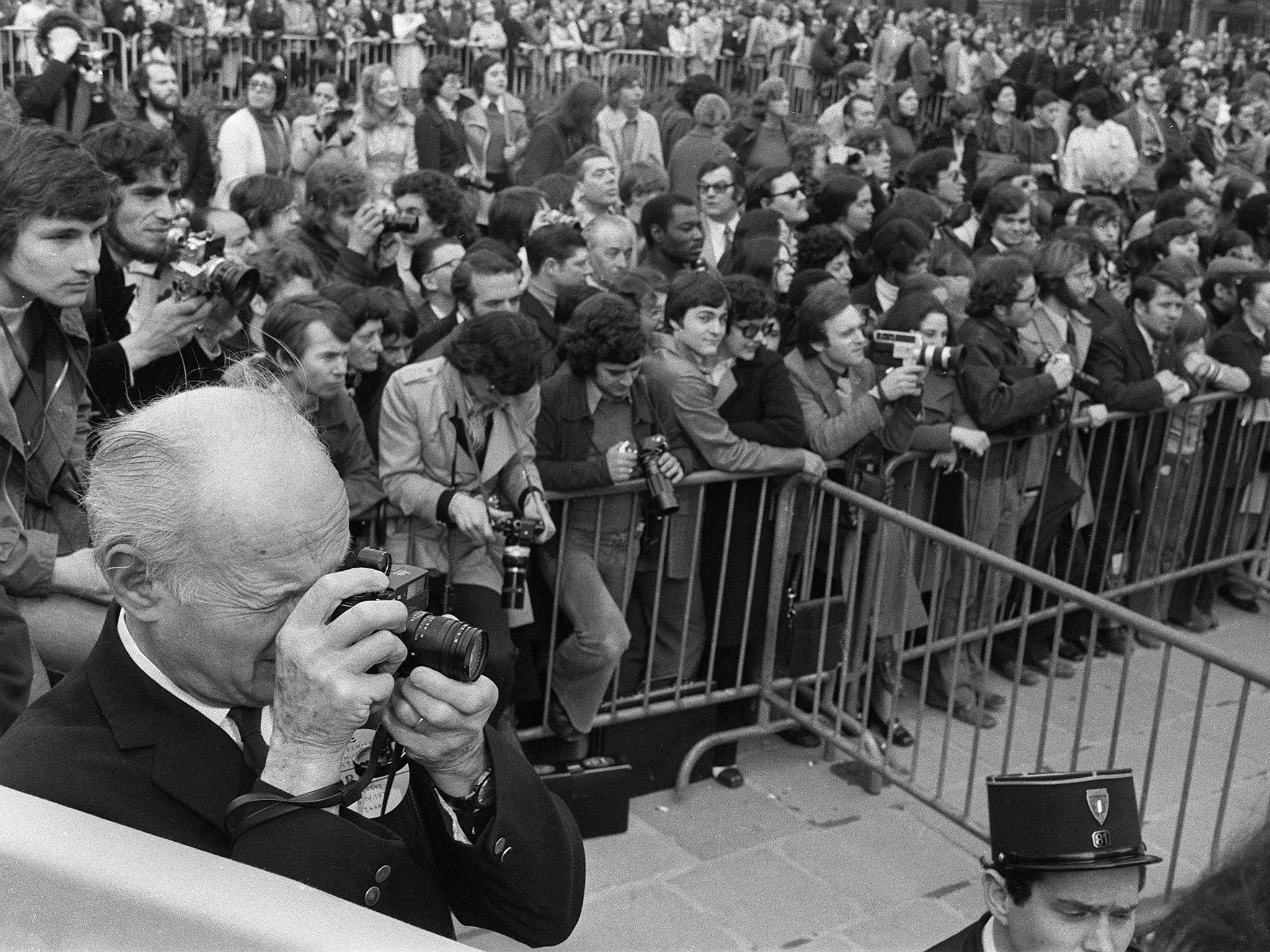

He was a pleasure to work with, as I found when doing a series of profiles for Vogue in the mid-Sixties. Always professional and modest, he’d arrive at the locations with two Leicas set with different light speeds of film. Glancing about, he’d put one aside and, taking the appropriate one, he’d move about looking for the right background while you interviewed the subject.

Most of the subjects were surprised that he didn’t ask them to sit or stand this way or that. But it wasn’t his way. “Just talk to Adrian,” he’d say in the perfect English he’d learned from a year in Cambridge in his youth. “I’ll just stay in the background.” Which is what he did, almost invisible, a craft he revealed he’d learned from his time in the French Resistance during the war.

The mechanics of photography or printing didn’t interest him except in so far as it was useful to his eye. He never went in for the prepared still, flash photography or the zoom lens. He didn’t take to colour. Nor did he care for the monumentalisation of image which has become such a feature of modern art photography. Look for the background, search for the telling detail and wait for the moment to snap was his approach.

It is a mistake to categorise him primarily as a photojournalist, however, although that is how he achieved fame as a founding member of the Magnum co-operative after the war, travelling the world to take photographic essays of time and place. His first love was painting and drawing. It was what he studied in Paris in 1927, after school, and what he returned to when he gave up professional photography in the mid-Seventies. He never succeeded as an artist, and destroyed most of his early efforts. But it gave him an entrée into the artistic circles of Paris in the fervent and fertile years of the late 1920s and early 1930s, when Modernism was its height and communism all the rage among intellectuals.

It also introduced him to the Surrealists. Half the history of modern art and a great deal more photography could be viewed through the lens of this movement. It taught the importance of the ordinary photograph as a revelation of life, the juxtaposition of ordinary images to create extraordinary meaning and the search for the telling in the detail.

Cartier-Bresson took the lessons with considerable application. He would search first for the resonant background and then wait for somebody to come into the picture. There’s a fascinating sequence of early pictures in the exhibition which show just how patiently he prepared for the “decisive moment”.

The style became more natural and spontaneous to him as he became more professional. It is from the early Thirties, when he travelled around France and in Africa and Europe and his year-long sojourn in Mexico (where Surrealism had taken strong hold as a movement) that many of his finest and most experimental pictures belong – the prostitutes in Mexico, the children playing in a broken wall in Spain, the dockworkers and sailors in Côte d’Ivoire and the window dummies in France and Germany.

Deliberately rejecting the opportunities to photograph local ceremonies, which he saw as a form of exoticism, he concentrated on the face of the ordinary in square and back street. The exhibition is particularly revealing of the way that he constantly tried out different compositions from the street scenes taken from a high vantage point to the still lifes of rotting food and the landscapes of structured lines.

In the end, he rejected most of the self-consciously artistic shots, partly on the advice of Robert Capa, with whom he shared a studio at the time, in favour of the quick snap taken with an eye for the precise composition and detail.

As fascism rose and Nazi Germany threatened he returned to France to work for the communist newspapers. The series he took of the French workers at play on the Seine when they were given holiday rights are justly famous, fond and teasing. More of a revelation here is the group of photographs he snapped for the weekly Regards of the crowds at the coronation of George VI in London in 1937, many of them using periscopes which involved them facing away from the process. The Pompidou would have you believe that was a comment on the futility of royal occasion, which he didn’t directly picture at all, but what comes across is the photographer’s pleasure in the chaos and pleasure of crowds.

Eager to contribute to the cause, he saw moving film as the best means of promoting issues and shaping opinion, going to the Spanish Civil War to co-direct an anti-fascist film and joining Jean Renoir as a general dogsbody on some of his finest films. One of the rare delights of this show are the sequences from Renoir’s Partie de Campagne and La Règle du Jour in which Cartier-Bresson is roped in to act as a lascivious novitiate admiring the ankles of a nun and, of all things, an aristocrat taking target practice on a model worker in the latter.

The war itself found Cartier-Bresson, who had joined up as a corporal in the Film and Photo unit of the army, a prisoner of war. After nearly three years in a camp and two attempts at escape, he succeeded on the third and joined the Resistance. It taught him, if his retiring manner hadn’t already achieved it, the necessity of anonymity and discretion. His film and photographs of the delousing of freed internees at Dachau are remarkable not just for their unsparing eye but their mood of pain suffered.

The Magnum co-operative was founded in 1947 and Cartier-Bresson was given India and China as his specialist fields. The shots he took of Gandhi’s funeral (he had had a session with him hours before his assassination) and of India divided are remarkable documents of their time. But it is to the pictures of humanity rather than history that one goes – the women praying to the horizon in Srinegar, the monk walking through the steam funnels of Mount Aso in Japan and the rhythmic shots of groups he shot in Jerusalem, Scanno in Italy, Oaxaca in Mexico, Prizren in Kosovo and almost everywhere else he travelled.

Colour he rejected as a diversion from the proper art of photography and the exhibition includes an intriguing little section on the colour portfolios he did shoot, reluctantly, for Life and other magazines. They are composed just as they would have been in black and white and could work just as well reproduced that way. But they are also shot with an artist’s eye for the pattern of colour.

He withdrew as partner in Magnum in 1966, feeling he had gone as far as he wanted in reportage and feeling out of kilter with the way the co-operative and photography were going. Instead, he chose to concentrate on the more artistic, and composed fields of portraiture and landscape. They were areas where his artistic sense of composition and the context could find more expression. He was particularly good at catching artists in their moments of contemplation or activity and it was to art he returned in his last years, although he was rarely found without a camera on his walks.

A wonderful exhibition of a wonderful man, a great artist of a medium he always denied was properly art.

Henri Cartier-Bresson, Centre Pompidou, Paris (centrepompidou.fr) to 9 June

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments