Frieze Art Fair 2014: A picture of wealth

Frieze week saw everything from old masters to young pretenders and giant sculpture on show in London. Karen Wright rubs shoulders with the super-rich collectors at the fair, tours the gallery openings and wishes she had £11m to spare

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.If people asked what would I miss if Frieze was no longer a London fixture, I would say Gerhard Richter, Richard Serra, Richard Tuttle, Sigmar Polke, William Kentridge, and Pedro Cabrita Reis. The Frieze effect has been the affirmation of London as a centre of art in a way unthinkable even five years ago.

With the proliferation of world-class galleries showing confidence in the city, the commercial stakes have risen steadily. What’s more, the juggernaut shows no sign of slowing down. When I ask Angela Westwater from Sperone Westwater, a blue-chip gallery from NY at Frieze Masters how their fair was she says, “We’re pleased to be back for our third year and looking forward to our fourth. We’ve seen good collectors and sold well.”

Frieze London itself is this year housed in a newly designed tent by Universal Design Studio in Regent’s Park and thankfully seems less cramped and airless then previous constructions. Its sister across the park, Frieze Masters, seems, as always, more opulent, as Brueghels jostle with great works of Arte Povera and modern masters.

It is, nonetheless, a shop, and consequently everyone brings their wares, piles them up tastefully, lights them and opens the door hoping to do well. It is always hard to say how people are doing but it seemed that trade was brisk when I wandered around, and I did see objects to covet. The problem is with such a plethora of things to see it takes a very experienced eye to make any real discoveries; one seeks already-known artists. I fell upon two video works and a wall of drawings on newspaper by the South African artist William Kentridge on Marian Goodman’s stand, to be reminded that the great artist was speaking in an hour in the “other tent”.

The talk was packed and was, as could be expected of a fair that dares to call itself Masters, pretentious in its presentation – matching an artist with an important academic and museum; in this case the Courtauld Gallery and Ernst Vegelin van Claerbergen. What transpired, though, was captivating, or at least it was when Kentridge spoke, telling the adoring audience about his researches into looking for solutions to problems – in this case how to present dead heads. We heard about how a master crafts his work, scavenging for ideas. At one point, he said poignantly: “Looking at Rembrandt drawings are object lessons – reminders of what you will never achieve.”

If one judges artists solely on their position in the marketplace then several of the big hitters were revealed in gallery shows this week. German artist Gerhard Richter opened the new, sublimely beautiful David Adjaye-designed space for New York gallerist Marian Goodman in style. There are eye-boggling stripes and splodges, carefully but seemingly casually crafted. Everything is shiny and new.

Across town, Gagosian’s Britannia Street gallery is showing American sculptor Richard Serra. Serra, now 74, works big and this show is no exception: there are only four sculptures in the capacious space and they are whoppers. At a recent press conference my fellow journalists wanted only to ask Serra about the resemblance to a cemetery of the work Ramble (2014), a group of 24 weatherproof steel plates of varying sizes (weighing in each between 5,100 and 12,200kg). While the forms are indeed upright slabs their resemblance to a cemetery ends there. The steel has an extraordinary patina that resembles a beautiful abstract painting, recalling Monet’s Water Lillies, and has been carefully worked. In the past I have felt threatened by Serra’s surface, careful not to brush too close to them as they might scratch, but these have been treated and refined. As one wanders among them, finding fleeting passages of beauty, it is easy to forget that you are in a central London gallery space.

The show peaks for me in a work titled Backdoor Pipeline (2010). At 49,081kg in weight it is a mighty piece. Entering through its arched door, resembling a Gothic cathedral, I cannot see the exit ahead as it curves around. Being contained in its interior space, aware of its contours and magnified sounds, the experience of being in a tunnel is echoed, and it is electrifying.

London Angles at Sprovieri Gallery is a stunning show by Portuguese artist Pedro Cabrita Reis. While Serra imposes his works within the architecture, Cabrita Reis here works with the space. Three sculptures in the smaller space, London Angle 1, London Angle 2 and London Angle 3, play with material, including light; each uses a different frequency, shedding degrees of warm to cool light, and are supported by various materials. The works, like many of the minimalist artists of the Sixties, including Dan Flavin and Fred Sandback, call attention to their surrounding architecture and define the space. But Cabrita Reis’s work is always multilayered, drawing upon the solutions of minimalism while ultimately turning away from them.

Nearby, Unframed #7 (2014) is composed of double glass, enamel on aluminium, fluorescent light and an electric cable hanging frayed and plugless: a useless light transformed here by this imaginative artist into a work of potentiality. I caught up with American artist, Richard Tuttle as he was installing his large show at the Whitechapel Gallery. His first words to me were, “I like my work in domestic settings better. I don’t like them in white cube spaces like this one.” When I entered the large gallery downstairs I had to agree with him. In the past, I have seen shows like his Whitney (New York) exhibition of 2005 that completely convinced me of his importance as perhaps America’s greatest living sculptor. He is the antithesis of Serra, a man who made humble gestures and modest marks immense.

There is one work here at the end of the space, Fiction Fish (1992), almost lost in the space but also capturing and owning it: raised a bit off the floor, a roughly constructed cardboard box surmounted by a woven ribbon cylinder; a simple, hand-drawn graphite line demarcating its space in the gallery. Behind a protective stanchion, and sadly not the only work protected this way, they seem to be contained in some strange zoo-like cages. This could add some creative tension but sadly does not, the simple drawings in string, Ten Kinds of Memory and Memory Itself (1973) look strangely emasculated. I ask director Iwona Blazwick whether all this protection is necessary and she smiles. “Loan conditions; there was one we had to fly business class from the States with its own seat next to the courier.” The preciousness of the work, because of its value, again seems to skew its presentation.

Tuttle has also done this year’s turbine hall commission at Tate Modern: a strange commission, you might think, for an artist who usually works small. When I query him about the unusual scale he has produced for the space, he says that I am “confusing size and scale. I see this space as an outdoor space, a continuation of the footprint of the area and I have worked accordingly. I thought of it with people underneath it bringing it to life. The artist has an intention, and the public change the intention.”

It is an extraordinary sculpture, spanning the distance from the bridge mezzanine to the end windows, showing its rawness of materials: MDF and fabric that was dyed in India, using the primary colours of Western art – red, yellow and blue – “a midnight blue”, Tuttle says. “It follows the light of a day, pink of dawn, yellow of midday and the blue of the evening”, and there is not a cage to be seen.

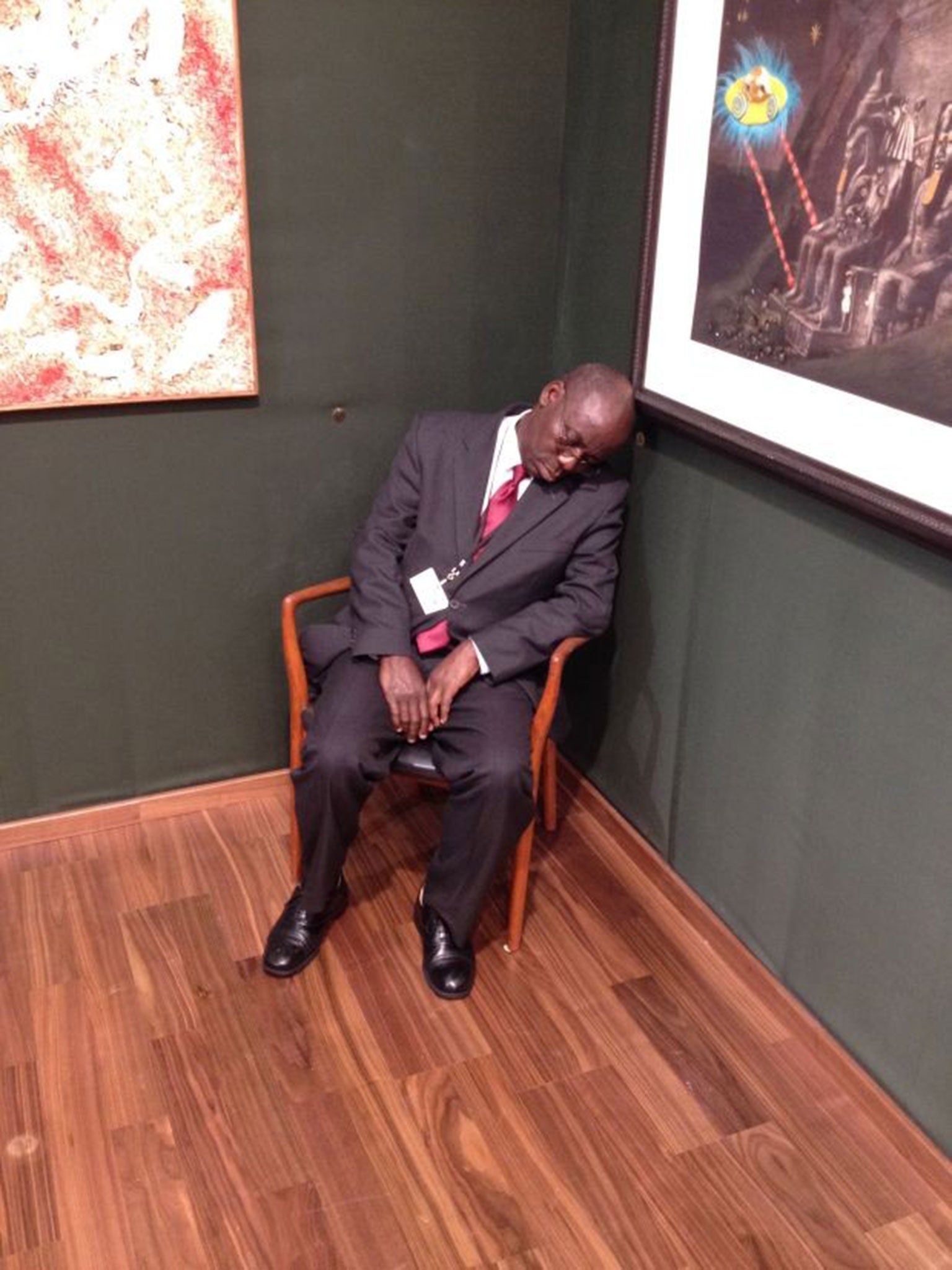

So, what will stick in the mind next week when the collectors move en masse to Paris for FIAC, the next date in their endless diaries? The Mark Wallinger-curated Hauser and Wirth booth at Frieze, featuring, among many other wonderful works, Sleeping Guard (2009) by Christoph Büchel; Kentridge’s description of “artist as hyena”; the modesty but stature of Ugo Rondinone’s Still Life (2014), perfect replicas of pears of painted bronze and lead on Sadie Coles’ floor (if only my handbag was big enough!), and the joy of yodelling in Serra’s steel tunnel (if only I had £11m). And what’s more, it is only another year until it starts all over again.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments