False memories: What would it mean if our most precious recollections had never happened?

Some of your most cherished memories may not be as reliable as you think they are. So an artist who has spent the past three years collating 2,000 examples of false memories tells Kate Hilpern

When, in 2012, the artist AR Hopwood started inviting the general public to submit examples of false memories – recollections of the past that they later discovered had never actually happened – he was more than a little apprehensive. "While scientific researchers in the field – with whom I regularly collaborate – have overwhelmingly proven that our memories can sometimes be inexact and are often entirely fictional, that's a difficult concept for people to get their heads round. So I wasn't expecting more than about 25 submissions," he laughs. As it turned out, he received more than 2,000 "memories" found to be entirely false, ranging from the humorous to the chilling, the surreal to the everyday.

"I was blown away," admits Hopwood, who has spent the past couple of years collecting the anecdotes (15 of which are published here, overleaf) as part of his touring exhibition and events series The False Memory Archive. "I underestimated just how much the concept of memory captures the imagination. But I suppose it makes sense when you think that we are more involved with the presentation of our lives than we ever have been – whether that's through social media or therapy culture, where autobiography and the understanding of our past holds particular importance."

Providing fascinating insight into the funny, obscure and uncomfortable things people have misremembered, these accounts have now been edited for a new anthology, which also features essays from renowned psychologists Professor Elizabeth Loftus and Professor Christopher French. "How seriously should we take the story we tell about our lives? That's the question I want to get people asking," says Hopwood, whose collection forms part of his exhibition, which in turn makes up part of the Wellcome Collection's States of Mind season.

The fact is that details of childhood memories – colours, the weather or the time of an event, for example – can't be accurately recalled, so our brains fill in gaps with invented details. Nor is it possible to retain long-term autobiographical memories before the age of three. Moreover, memories – childhood or adult – are recreated every time we remember them. Sure, there are traces from the original experience, but post-event information is added on – things people have told us about the event, our own expectations of how we think events would normally pan out, cultural beliefs, photos and bits from other memories, to name a few.

Cara Laney, a professor of psychology at Reed College in Portland, Oregon, explains that memories are a bit like building a wall of Lego – each time you try to rebuild it, it will never be exactly the same. Then there are entirely fabricated memories – some obviously so because they're about pre-birth, flying, seeing fairies, being born or dying, for example – which can nonetheless be remembered with absolute clarity.

Psychologists have even found that false memories can be planted. "Study after study shows that suggestive interviews can get people believing a whole raft of things, such as being attacked by a vicious animal in childhood right through to having witnessed demonic possession. In every case, substantial numbers of people didn't just believe it happened – they gave emotional descriptions," explains Hopwood.

For the artist, this is by far the most captivating aspect of memory. "If some people can be coerced into remembering something that didn't happen or they didn't originally remember, the implications are huge. Much of our legal system, for example, relies on eyewitness testimony, yet we know that if, say, a group of people sees a cyclist knocked off a bike and they hang around and discuss the incident afterwards, and the dominant member of the group has a different memory, the others could conform to this stronger view. We also know that certain forms of questioning can lead people to 'remember' certain things. Then there are juries, who generally follow the common-sense idea that the more detail someone remembers about an incident, the more likely it is to be true – whereas in fact the opposite is the case."

Therapy is also implicated. "If someone starts plumbing the depths of their past and remembers things they didn't when they went into that setting, there is, of course, a real danger that they may be creating false memories – although it has to be said that both the legal system and therapists are starting to take this on board. For me, though, it's the everyday implications that are most intriguing. I find it liberating that our perception of the past could be so error-strewn."

Such is the depth of Hopwood's knowledge that it's easy to mistake him for a psychologist. "Once you stumble across the extraordinary body of research, it's hard not to become evangelical about it," he chuckles. "This idea that we can believe in a memory of something that hasn't happened – it's just so seductive, isn't it? So for me, as an artist, I couldn't wait to explore how I could add a different kind of voice to the science."

Hopwood's work aptly fits into the States of Mind season – a changing exhibition in which artists, psychologists, philosophers and neuroscientists interrogate our understanding of the conscious experience. "If, as is the case, our memory is so open to distortion, then it follows that our whole identities may be constructed around a series of distortions," he says. "In the end, we are creating our own fictions."

To download AR Hopwood's book of false-memory testimonies: falsememoryarchive.com. States of Mind: Tracing the Edges of Consciousness is at the Wellcome Collection, London NW1, from 4 February

Fifteen imperfect recollections drawn from AR Hopwood's False Memory Archive

1. Ten years ago I was interviewing a doctor about pain for a radio programme. I clearly remember putting my arm into a bucket of ice as part of a test of pain tolerance. The agony was extraordinary as the pain slowly spread up my arm, and it wasn't long before I had to withdraw my arm. A few years later I gave the tape to a producer for another programme we were doing on pain. She listened to an hour of audio, but at no point did I put my arm into the ice bucket. A man and a woman did, but I didn't.

2. A visit to London in the early 1980s resulted in the happy occasion of a visit to the hit West End musical Cats. I regaled everyone at school with this highlight of my trip and my mum bought the soundtrack album. I spent every Sunday next to the record player for weeks on end, learning the words to each song and "rehearsing" for when I was old enough to go back to London to star in it myself. Over the next few years, I would enthusiastically announce, when it came up in conversation, that I had been to see Cats when visiting London aged around eight – until one day, in about 2001, when I realised with complete clarity that I had invented the entire thing. I asked my mum: did we ever go to see Cats when we were in London? No, she replied, we did not.

3. I got into a car accident and totalled my car and I distinctly remember three different cars hitting me after I hit the first car; but no cars actually hit me.

4. I remember falling off a merry-go-round, but my mum said that it happened to my sister before I was even born. Strangely enough, I have the exact same scar that she has from the accident, but my parents have no idea how I got it.

5. I have a vivid memory of my mother serving me dinner one evening when I was about four or five. It was sausages, mashed potato, vegetables and gravy. I went to eat the meal outside on my small trampoline. I remember looking down into the gravy to see all these unpleasant insects swimming in the food. I screamed and ran indoors to show my mother. She said I was being hysterical and that there were no insects in the food. She promptly ate the whole dish, with me watching her spooning the little black,winged bodies into her mouth, while she exclaimed how delicious it was and what a shame that I had missed out. Usually I give animal cruelty and health reasons as the explanation for my vegetarianism, but when questioned recently by my mother as to why I had rejected meat for so many years (I am now 26), I explained the real reason. I was confused to find out from her and other family members (who had been there) that this whole episode was merely a disturbing and very vivid fabrication on my part!

6. When I was around six or seven I would drink milk and believe it would make me fly. I physically remember an uplifting feeling and flying across my living-room floor and having a bird's-eye view of the carpet.

7. At the head of a string of lakes, through the woods, at the end of Walmsey Lane, is a house I went to often in my childhood summers. The house never existed.

8. I was convinced a girlfriend had a sister who had died at the dentist. I had even told my parents about it. Over dinner one day [my girlfriend] said she was going to the dentist the next week. It all went quiet at the table and my mum said it must be hard for her to visit the dentist after what had happened. It turned out that this had never happened, I must have had a dream that to me became real. I had kept my own [dental] appointments secret for fear of upsetting [my girlfriend] and never brought the subject up, thinking she would talk about it when she was ready.

9. My teddy bear ate pasta.

10. An acquaintance was murdered and the policeman, when he conveyed the news to me at midnight on the day it happened, said I would be called as a witness. Before going to bed that night I wrote everything down exactly as it had happened. Two or three weeks later I was called to give my statement. I was sure I had all the details clear in my head, but just to confirm everything before talking to the police I re-read my notes – the first time since the murder day. I was astounded to discover that my memory of the event was quite different from my notes. I had been quite prepared to swear in court that my memory was correct, but obviously it had been coloured by other people's ideas about the case and I had woven them into a plausible story. I used the notes.

11. I misremember one evening riding with my parents in their car in Attalla, Alabama. I think I was around three, so this would have been about 1966. My aunt was there in the back seat with me, and we played some sort of singing game. Why was this a false memory? Because at one point a giant dinosaur, Godzilla-like, rampaged through the streets behind the car.

12. I remember as a child playing on my dad's lorry in the desert. He was a driver in the RAF, in Aden. My father returned from Aden over 10 years before I was born.

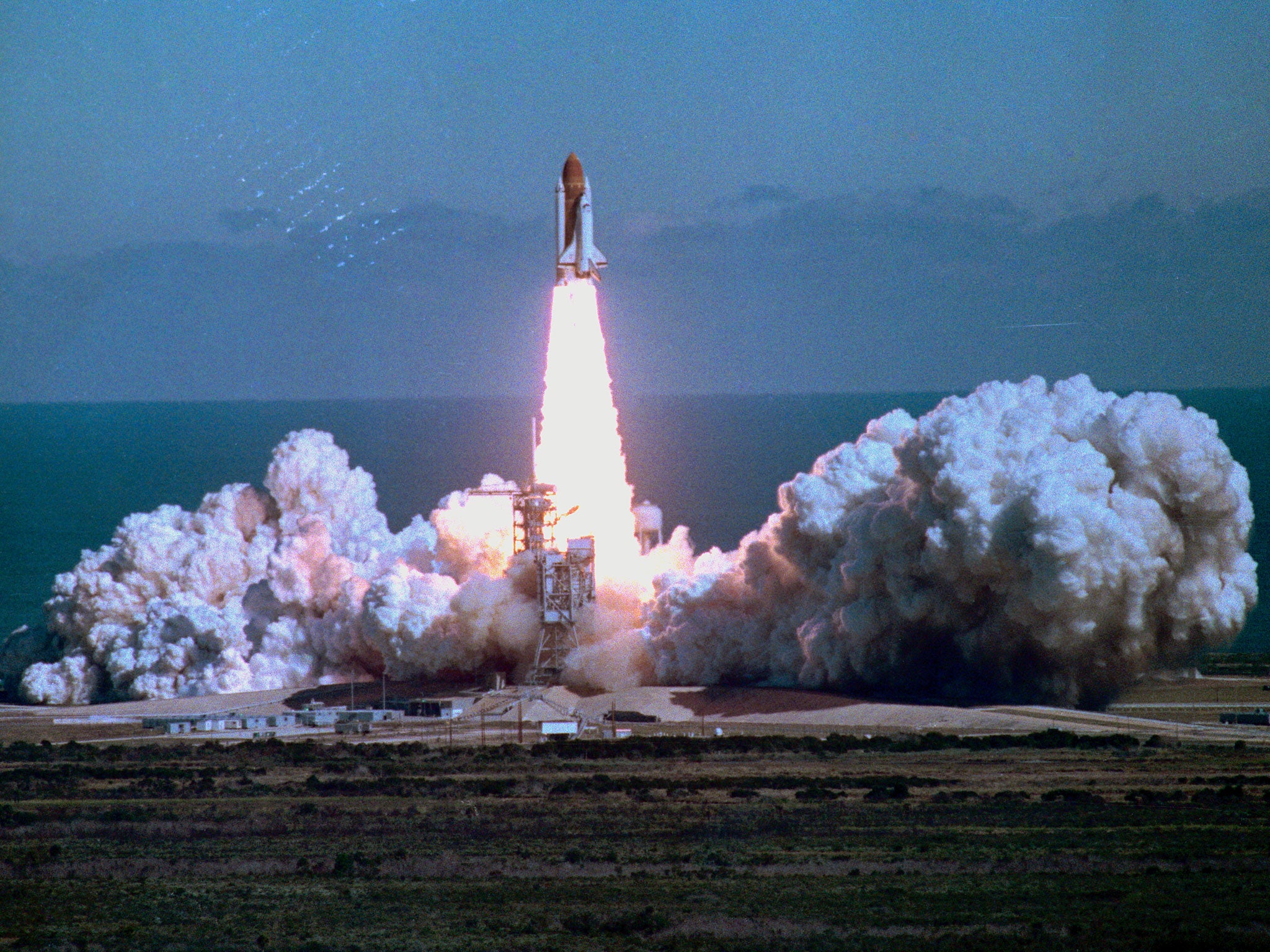

13. I have a very vivid memory of watching the Challenger shuttle disaster in high school. I was standing in the science/media library in my school, and there was a TV on a tall metal rolling stand – the kind that was rolled into classrooms for presentations. Several of my friends were there. I can remember exactly how I was standing in the room, where I was, the angle I was seeing the screen from, the shock of others in the room. The problem? The Challenger disaster happened two years after I graduated. When it occurred, I wasn't in that high school, or that city – I was living in another part of the country.

14. I have a memory that I was standing on top of a train and the train went through a tunnel. I died.

15. As a young boy, I was convinced of the reality of my older sister. I had a complex relationship with a female character in my mind. As far as I was concerned, we spent lots of time together and were extremely close, but she was much older than me; in her late teens, maybe 20. I was convinced that for some reason she was no longer living with, or in contact with us. I was so sure of these facts that I asked my mother about my "sister", to which she replied that no such person existed.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies