Egyptian mummies: Science or sacrilege?

A blockbuster exhibition at the British Museum unwraps the mysteries of 5,000-year-old Egyptian mummies. Zoe Pilger is fascinated – but not sure they should be on show at all

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.A shocking photograph of an Egyptian mummy unwrapped greets the visitor to a new exhibition at the British Museum, Ancient Lives, New Discoveries: Eight Mummies, Eight Stories. The photograph was taken in 1908, when the pillage of sacred "curios" from around the world was at its height, and Egypt was under British rule.

The image is painfully symbolic; it shows the skeleton of the 12th Dynasty male Khnum-Nakht laid out on a table. The cloth in which he has been wrapped for thousands of years lies around his remains. A team of scholars are standing over him, including the pioneering Margaret Murray, who was the first woman to be appointed a lecturer of archaeology in the UK. She wears a white pinafore and her hair is wispily pinned up. The unwrapping took place at the Manchester Museum in front of a crowd of 500, eager to see a mystery – literally – stripped.

Mummy unwrappings or "unrollings" were popular public spectacles in the early 20th century, when Egyptology was a new academic discipline. The photograph points to a violation. By cutting open the mummies, scholars and collectors destroyed the fragile layers of embalmment, arranged with care after death in order to ensure the person's existence in the afterlife. For the ancient Egyptians, the protection of the body was paramount.

In 1908, there seemed to be little fear of the supernatural wrath incurred by the disturbance of the dead, but in 1922 Howard Carter would famously discover the tomb of King Tutankhamun. Mummy mania was born. Some of those associated with the expedition died in mysterious circumstances; "the curse" of the mummy was dramatized in the media. "Death, eternal punishment," booms the voiceover of the 1932 Hollywood film The Mummy. "For anyone who opens this casket."

Cultural historian Roger Luckhurst has argued that "the curse" was in fact an expression of British colonial angst and fear of Egyptian independence, which was emerging in the 1920s. He describes too the importance of the British Museum, which was established in 1753 and acquired many mummies in the 19th and 20th centuries. Eight of those are displayed here.

This exhibition considers how we can understand the mummy in a non-invasive way using the latest CT technology. Rather than cutting open the mummies, these days institutions like the British Museum are legally bound to be sensitive. They must bear in mind that they are dealing not merely with the remains of real human beings – however long dead – but also those from other countries, acquired during a time of empire. The question of how and why they came into our possession in the first place is a significant one. However, it is not explored here.

Instead the curators' aim is to illuminate not only the deaths but the lives of eight very different individuals from the ancient world – and in this respect they succeed admirably. The mummies range from a seven-year-old temple singer to a doorkeeper. There is a magnificent gold coffin which conceals a two-year-old, his head lowered. There is a man with a beard painted on his face and feminine breasts fashioned out of padding. They come from Egypt and the Sudan, spanning 4,000 years.

I was absorbed and utterly transported. Much precious documentation was lost during careless discoveries in the 19th century and there are gaps in the stories that the curators tell with such skill – though this only makes us use our imaginations. We have to dream up the rest.

There is another poignant and surreal photograph, taken recently, which shows an embalmed mummy being loaded into a CT scanner at the Royal Brompton Hospital. The mottled, yellow-brown surface of the body is contrasted to the white clinical environment. This is how the interior of unwrapped mummies is now investigated: sophisticated digital visualisation allows us to see 3-D images of everything beneath those cloths – from tooth abscesses to undigested food in the gut to approximate age, sex, and status.

The first mummy on display is extraordinary. It seems charged with a supernatural energy and I half expected it to wake up. This young man was in his twenties or early thirties when he curled up into a foetal position and died. He was buried in a cemetery in Gebelein, Upper Egypt, and naturally mummified by the dry, hot sand. His remains are 5,000 years old but his presence is vivid.

Most of his skin has been preserved: it covers his delicate bones. His feet are drawn up to his chest and his hands are cupped under his chin, as though pleading. He seems vulnerable, lit in a glass case in a dark room like a relic. He has been transformed into an object and put on display. To look at him provokes a primal feeling of horror. This is death made real.

On the wall behind the mummy, there is a 3-D film that shows his body slowly appearing and disappearing, detailing his internal organs, his hair and nails, which are also preserved. The combination of ancient human remains and cutting-edge technology is dystopian. I couldn't stop staring at him; for children, this will be a thrillingly macabre experience.

Indeed, one of the strengths of the exhibition is that it manages to cater to both children and adults. There are interactive touch screens whereby you can unfurl the layers of each mummy, but also fine historical detail. I was most intrigued by Tamut, a high-ranking priest's daughter from Thebes, who remains encased in her magnificent gold, blue, and red coffin, which has never been opened. By the magic of technology, she is now revealed – her innards, as well as the stunning array of amulets placed on her body after death.

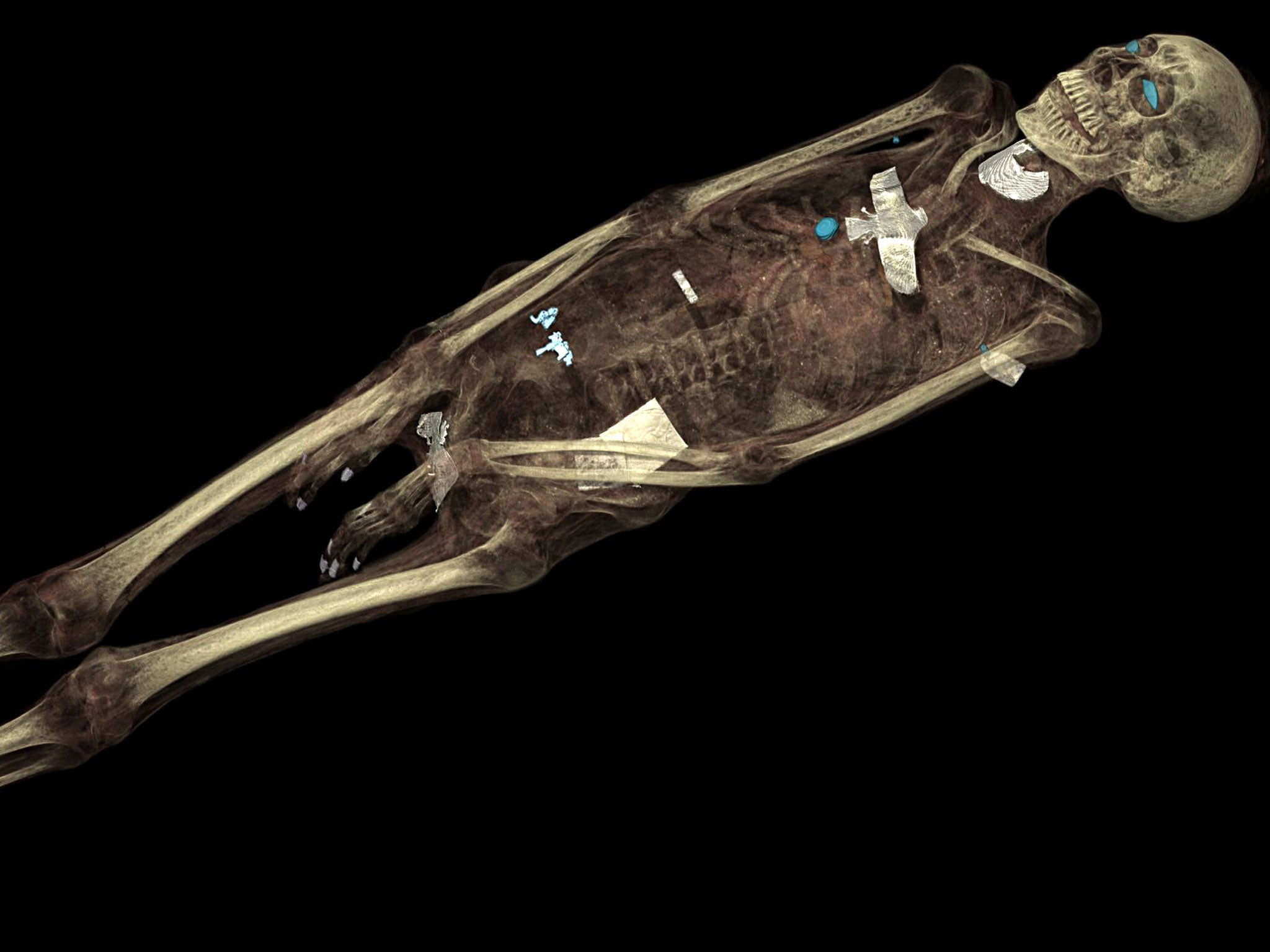

The CT scan of her body is eerie. It shows a corpse adorned. Blue artificial eyes made of glass or stone have been placed in her eye-sockets; there is a blue scarab on her heart, a winged deity on her throat. These charms could be activated with spells from the Book of the Dead (circa 1450BC). Decayed though exquisite sections of papyrus from the book are displayed here. Spell 151 is written on the wall: "I bring your heart to you. I set in place in your body for you." The heart, rather than the brain, was believed to be the centre of consciousness in ancient Egypt.

The process of embalming was heavily ritualized: after 35 days of drying out the body, Tamut's brain was removed from inside her head with a hook inserted through her nostril. Her face was padded with textiles. This was cosmetic: the skin would lose its plumpness during the drying period and become wrinkly. The other internal organs were removed, bundled up, and then reinserted into the body: the wound in the torso was sealed with a wedjat, or Eye of Horus, which had healing power.

Although Tamut's coffin has not been disturbed, the act of exploring her insides with the aid of a CT scan nonetheless feels like trespassing. These bodies were not designed to be seen. There is a tyrannical tendency in Western culture to try to know everything – to decode, demystify, and disenchant even the most sacrosanct of secrets. A fascination with the "magic" of other cultures is coupled with a rationalist incredulity. We don't believe, and yet we can't stop investigating – historically, through violent methods.

The curators of this exhibition seem aware of this danger. Rather than crude unwrappings as a form of public entertainment, these mummies are explored with scientific rigour and respect. Instead of revulsion, we are encouraged to feel a sense of shared humanity; they are dignified through the small detail of daily life – from the wigs they wore to the beer they drank. However, there is a feeling that they do not belong to us and should not be here.

Ancient Lives, New Discoveries: Eight Mummies, Eight Stories, British Museum, London WC1 (020 7323 8181) Thursday to 30 November

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments