Don’t put a price on our national treasures

Cultural institutions are not businesses and should stop selling off Britain’s valuable artworks, says Tiffany Jenkins

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Two important paintings, once on display at the Royal Cornwall Museum, have been quietly auctioned at Christies in London.

The pictures – Bondage by Ernest Normand and The Sea Maiden by Herbert Draper – are flamboyant pieces of Victorian erotic art. Under the hammer they commanded about £1m each. The Chairman of the Royal Institution of Cornwall, which owns and manages the museum, Sir Ferrers Vyvyan, said: "We are delighted with the outcome of these sales, particularly in today's market.

"The reality is we have had to take some extremely hard decisions and the money realised by the sale of these paintings is a real step forward in ensuring the long-term stability of the RIC and the Royal Cornwall Museum." So what will the museum spend the money on? They plan to place the cash in an endowment fund.

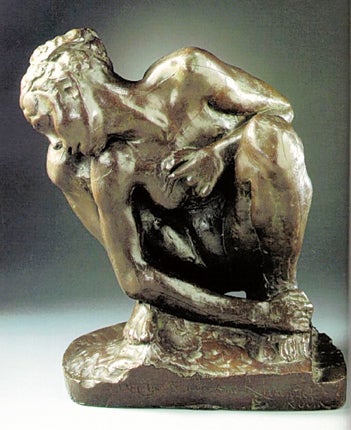

The RIC isn't the only one flogging the family silver. Southampton City Council tried to sell Rodin's sculpture Crouching Woman, and Alfred Munnings's oil painting After the Race, to contribute to a new maritime museum about the Titanic. Thankfully, after a major outcry, the sale stalled at the last minute. In the end, they found the money from a lottery grant.

Museums are not businesses and they shouldn't sell off their treasures to mend the roof or pay the electricity bill. Until recently, there was a strong presumption against any disposal of objects and art in the cultural sector. Indeed, national museums are only permitted to sell – or even exchange – collections, in rare circumstances, such as when it is a duplicate of another in their stores.

In the United States, so concerned were they about threat of the current financial climate, the Association of Art Museum Directors introduced a policy that forbids the use of funds raised by selling collections to cover museum operations.

Not so in Britain. Two years ago, the Museums Association, the professional body for the sector, significantly altered its policy on the care of collections, revealing a softening of attitudes towards the protection of the collection. In the Disposal Toolkit, the MA came out and argued for the first time that financially motivated disposal was permissible in certain circumstances and not just to buy another work, but to raise cash.

It is important to remember that the few times this has taken place it was bitterly regretted years later. Birmingham Museums and Art Gallery's Collecting Policy 2003-8 laments the sale of their South Asian and Far Eastern metalwork in the 1950s as "an act of irrevocable rashness".

As it points out: "It is not only fashions that change ... the society which a museum serves can also change ... the metalwork would have gained greatly in relevance in view of the growing contribution of South Asian communities to modern Birmingham."

It will also be difficult to persuade people to leave their treasured possessions if they think that in the long term the objects that meant so much to them could be flogged. The John Rylands University Library of Manchester lost an important loan collection as a result of its sale of books in 1988. It has found it hard to attract donations ever since. Then there are cases of objects let go in ignorance of their value. The V&A once sold a set of 18th-century gilt wood chairs thinking them to be "bad 19th-century reproductions". They were acquired by the then King of Libya. When it was subsequently discovered that the chairs were from a set commissioned by the Venetian Doge Paolo Renier, and of considerable interest, it was too late to try and buy them back; they had been converted into mirror frames and stools.

Let's keep the doors open to the public and shut to the salesman. Losing these treasures is too high a price to pay for short-term financial gain.

Tiffany Jenkins is the director of the arts and society programme at the Institute of Ideas

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments