Coal: A mine of culture

Why ignore the art of mining towns? Lee Hall, author of 'Billy Elliot' and 'The Pitmen Painters', and now curator of a season of films about coal, says we don't know what we are missing

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.To have written two shows about the British mining industry which are running concurrently in London (and will soon be together on Broadway) and now to be inaugurating an extraordinary season of films on Coal for the BFI is about as far from where I thought I'd be growing up on the Great Northern Coalfield 25 years ago.

As a kid in Newcastle in the Seventies and Eighties, the coal industry seemed like a monolith – it had been around forever (well at least since the Romans came), and it felt like it would remain for at least a millennium or so.

The coal industry was just the dust in the air. It held little interest to me because it was such a ubiquitous part of the culture. It was everywhere, so it was unremarkable. What I wanted to do was to get out from under this sooty blanket and seek other things, new worlds which were not so familiar. I wanted to be a writer not a bloody coal miner or shipyard worker.

By the time the 1984 strike was lost and I'd graduated from university I turned round to discover that the mining industry was literally vanishing before my eyes. Driving round the Durham coalfield in the mid Nineties, it was virtually impossible to find a winding gear. Within less than a decade the industry which was nearly two thousand years old was virtually wiped out.

Just 60 years previously it had reached its zenith with more than 1.2 million miners. Forty years previously it had been the pride of post-War Britain when it had been nationalised at the same time the NHS was inaugurated and the Butler Education Act secured schooling for all. Just 25 years ago 250,000 men worked underground – now there are less than 6,000. Not that we've stopped using coal – a third of our energy is still driven by coal powered stations – it's just that we ship it in from China or the former USSR.

But what is so remarkable about this enormous economic and demographic shift is that it so rarely rears its head above the parapet. Of course the coal industry wasn't the only one to go; steel, shipbuilding and most heavy manufacturing has now all been outsourced to the emerging economies out East. We have gone from a land which makes things to a land which buys things in a generation.

As a dramatist, such a massive cultural change is fascinating and as a person who grew up in the midst of it, it is especially so. The grand narrative that has been so easily swallowed seems particularly specious to me.

The industry was supposedly "uneconomic", and the country in the grip of philistine unionists; "modernisation" was needed to provide the freedoms necessary for a richer life. All of which seems to ignore the £36bn it has cost UK plc to dismantle the industry, the fact that the privatising of what we once held in common has, far from making our cultural lives richer, impoverished us with a dumbed-down diet which we are less socially mobile to escape. If you want to watch the football on telly now, or get your teeth done, or drink some water, or burn some coal, you not only have to pay for it, but very likely the profits will be siphoned off to France or China or some multi-national holding company. The supposed freedoms of the market are not necessarily freedoms for the consumer – choice is a little more illusory than meets the eye.

The battle over the mining industry waged in 1984 was, with hindsight, a battle over not only the future but the soul of Britain. That the failure of the NUM was a watershed in our political life is widely accepted, that it was a turning point in the spirit of the islands is only more recently becoming clear. Now that the idea that we'll make money out of money, instead of labouring for it, has taken a proper body blow, many of the received wisdoms of Thatcherism which have found their way into a post-84 political consensus should be seriously under question – although our political class seem disabled from seeing the bleeding obvious.

The idea of the miners as "unlettered beasts" is also ridiculous given any historical examination. The WEA, the pit head libraries, the brass bands, etc. were all legacies dating back to the growing self-organisation of the workers a hundred years ago. The miners were as interested in the world as they were in advancing their lot – and the arts and sciences were to be embraced rather than eschewed.

One such group was the Ashington miners who in the 1930s set out to learn a little art history but ended up being celebrated artists bought by major collectors of modernism. I stumbled across their forgotten story and realised it was emblematic of a self-generated aspiration which has withered with the industry which sustained it. I was stunned to find souls like mine, curious for knowledge, finding a gift and success in a field which we'd all dismissed as a preserve of the middle classes. The litany chanted by the gatekeepers of culture is that no one is interested in "class" any more, after all aren't we classless?

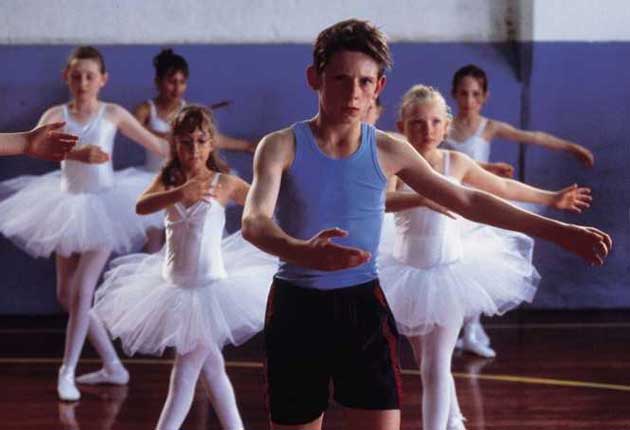

But, of course, my plays The Pitmen Painters and Billy Elliot: The Musical have been enormously successful precisely because they refuse to accept the orthodoxy that no one is interested. The debate about class, freedom, our individual and collective responsibilities, are not mummified relics but live and important to people from all backgrounds. Even the Tories are rethinking the debate. The Pitmen Painters has had four sell-out runs so far, garnered a sackful of major awards and is coming back to the National for a short run before a regional tour and a stint on Broadway.

Billy Elliot: The Musical, to my amazement and surprise, is a sell-out success in America, winning 11 Tony Awards this year, including Best Musical. It's a musical in the tradition of Joan Littlewood, rough, brazen, wearing its political credentials clearly on its sleeve, yet it has spoken clearly to an audience who have only the dimmest notion of who Maggie Thatcher was and who have never heard of Arthur Scargill.

But the plays also talk to an audience who now understand first-hand the "cyclical nature of capitalism" – as a character in The Pitmen Painters calls it. It's clear to the Americans on Broadway that even though Billy Elliot is "foreign", it comes from the land of Steinbeck and a democratic, humane and populist way of looking at the world.

I suppose the surprising success of the two plays spurred the BFI to ask me to be involved in their King Coal season – a magnificent retrospective look at the archive holdings. There are feature films, TV dramas, GPO public broadcasts and a rare chance to see some of the Mining Review films the coal board made themselves.

From 1947 to the mid Eighties, the coal board made over a thousand films celebrating every aspect of mining life. They were shown up and down the country in hundreds of cinemas. It is an extraordinary body of work and in it, to my complete surprise, I have found not only a 1950s documentary on the real life Pitmen Painters of Ashington which I had no idea existed, but also a film of dancing Yorkshire miners from the Forties who travelled the North performing a parody of Coppelia in tutus!

What is striking about these miners is not how hard they are – their tireless and dangerous work is of course taken for granted – but how civilised that society was. The thirst for learning was as strong as it was for ale. The sense of a national and common purpose for the industry is apparent in every film. Linking the industrial endeavour to a civic sense of a renewed society is stamped on almost every film.

What is clear in looking at the season as a whole is how uncoupled this joined-up vision of Britain was by the Thatcher years. One does not watch the films with nostalgia – there is little romance really in the dirty work of mining – but what is profoundly confronting is not Britain as it was but what we have become. What we have lost is a common sense – of purpose, of ownership.

As we watch an earlier age supposedly where class was so divisive, it is impossible not to have the gnawing sense that we are the ones atomised, ignorant of and disconnected from the other people with whom we share our lives. The dirty work was been outsourced. The unhappiness grassed over, photoshopped out. But here it is all laid bare, for good or bad.

Even if you have no interest in the mining industry, in the age of carboniferous capitalism, or indeed carboniferous socialism, even if you care little about British history – these films will still be of huge interest for they ask very big questions about the future of us all.

'Billy Elliot', Victoria Palace Theatre, London (0870 895 5577); 'The Pitmen Painters', National Theatre, London, 2 to 22 Sept (020 7452 3000), then touring. This Working Life: King Coal is at the BFI and cinemas across the country ( http://www.bfi.org.uk )

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments