Botticelli Reimagined: The V&A has assembled the grossest heap of kitsch and dross ever to litter its halls

Boyd Tonkin chastises the museum’s 'nasty' tribute to Botticelli

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.As the nation’s prime venue for applied arts, the V&A has a licence to thrill. Just as no one bats an eyelid to find rock-star memorabilia or catwalk creations in its rooms, so few visitors will bother much that Botticelli Reimagined opens with James Bond. Or rather, with Sean Connery as he wakes on a Caribbean beach to find Ursula Andress in a state of undress, emerging from the sea in Terence Young’s film of Dr No. It’s a witty and knowing allusion to the Florentine painter’s The Birth of Venus, then – in 1962 – on the brink of yet another round of recreation across media from fashion and photography to film.

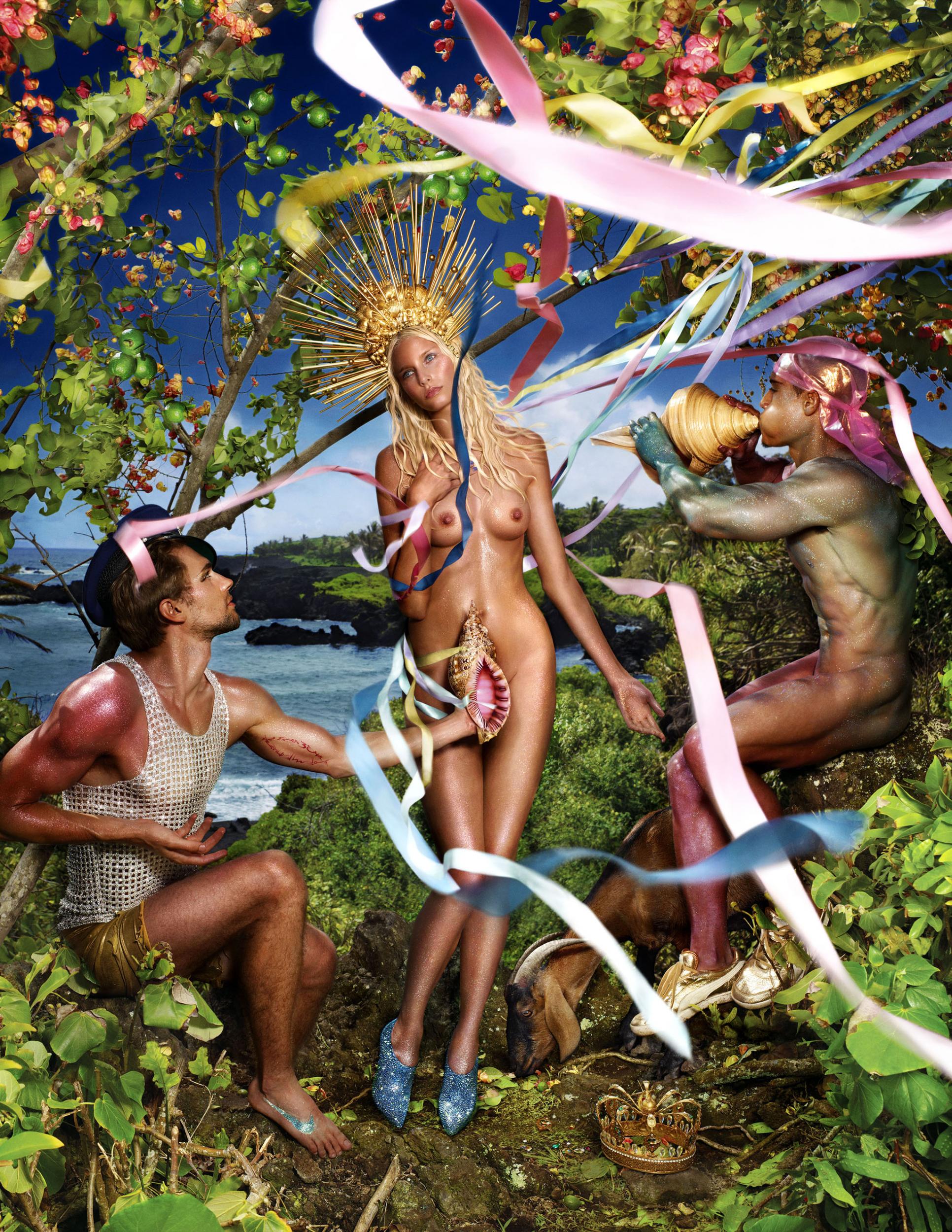

Only then does the real shock begin. In the show’s first section proper (entitled “Global, Modern, Contemporary”), the museum has assembled perhaps the grossest heap of kitsch and dross ever to litter its eclectic exhibition halls. From the soft-porn fantasia of David La Chapelle’s Rebirth of Venus to Dolce & Gabbana’s hideous Botticelli-in-fragments dress (from their 1993 collection), from Andy Warhol’s zombified mimicry of the goddess to Yin Xin’s vapid Chinese-featured Venus after Botticelli: we tumble from one circle of art hell to another.

The curators Mark Evans and Ana Debenedetti have consciously chosen to run their show backwards. So Sandro Botticelli’s recent afterlife of schlock-horror comes first. Then we encounter his 19th-century worshippers and imitators, and only then see some wonderful works from the main man – and his studio – himself. It’s the nature of that afterlife that turns the stomach. Debenedetti assures us that “every single work presented here has to be meaningful: we didn’t just want quotations and pastiches of Botticelli.” Meaningful, perhaps – but still nasty.

Cue some familiar curatorial mood-music about postmodern appropriation and the migration of iconic images through hi-tech media, fashion trends, feminist art theory, and so on. Yes, we know this old song. Still, a few works in this little shop of post-Botticelli horrors do strike home. Cindy Sherman has a typically sardonic but deeply artful photographic take on the painter’s feminine ideal. The Brazilian artist Vik Muniz’s version of Venus arises from a shore strewn with the graceless waste and clutter of modernity. That’s apt enough. Overall, the sheer ugliness of this room’s smug revenge on Renaissance beauty injures the eye and numbs the mind. Look out, though, for designer Elsa Schiaparelli’s 1938 evening gowns, elegantly enhanced by motifs from Botticelli’s Pallas and the Centaur (whom we will meet later). But then Schiaparelli was an artist in textiles, not a runway exhibitionist with a high-street chain and media toadies.

In the space devoted to Botticelli’s 19th-century rediscovery, things improve – if not always by much. As a vogue for Quattrocento art spread, those symbolic paintings of wistful lovelies in myth-laden landscapes proved a sometimes fatal attraction for artists torn between high thinking and base passion. From the 1820s, the winds of taste began to blow these works back into the European mainstream. In 1848, Ingres painted one of the Florentine’s frescoes on the wall in the background of his Nomination of a Prefect of Rome in the Sistine Chapel. A little later, with the Pre-Raphaelites in England, Botticelli fever breaks out in earnest.

From Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s flame-maned beauties to William Morris’s tapestry of nymphs in an orchard and Walter Crane’s sultry The Renaissance of Venus, these florid tribute acts pant and yearn with all the semi-sublimated sensuality of Victorian bohemia. The tortured eroticism speaks (or rather sighs) for itself. But pay attention to the cash flow too. In 1868, Rossetti paid £20 for Botticelli’s Portrait of a Lady Known as Smeralda Brandini (she turns up in this show). He sold it for £320, but flogged one of his own works to the same patron for £735. By 1899, however, Isabella Stewart Gardner of Boston had bought the so-called Chigi Madonna (also at the V&A) for the vast sum of $70,000. The price tags had begun to match the cult.

For the Pre-Raphs and other Victorians, Botticelli’s Primavera (his enigmatic allegory of spring) exerted the same grip on the imagination as The Birth of Venus did on post-1960s disciples. The pioneering Hamburg-born art scholar Aby Warburg made that pair of works the subject of his thesis in 1893. He inaugurated a century of erudite, even fanciful, interpretations of Botticelli’s mythology and iconography. True, some of the esoteric readings that saw the painter as an initiate and champion of a mystical neo-Platonic sect teetered on the edge of sanity. But through Medici court patronage, the artist did have links with the philosophers – such as Marsilio Ficino – who sought to reconcile paganism with Christianity. We find few traces of that network here. With its focus on the descent of technique and imagery from the 15th century to the present, the V&A show dumbs Botticelli down a bit. You need not credit the crackpot theories to detect a thinker as well as a draughtsman at work here.

Not that most visitors will mind once they get to the “Botticelli in His Own Time” section, and plunge into the works themselves. For instance, Botticelli’s Virgin and Child with Two Angels, from Vienna, proclaims a sharper, cooler – more modern – sensibility than you find in his 19th-century epigones. The National Gallery’s own Mystic Nativity has angels who might have strayed from Venus’s boudoir hovering in a ring above the holy family in their stable. Profane beauty and sacred truth in neo-Platonic harmony? The Birth of Venus and the Primavera don’t ever travel from the Uffizi in Florence, but the magnificent Pallas and the Centaur has. As the wisdom-goddess ruffles the hybrid beastie’s mane, does reason subdue passion? Mysteries linger. So does a sense of this artist’s restless versatility. It ought to modify the stereotype of those dreamy, wispy lasses barely clad in diaphanous floaty numbers. His Pentecost, for one, has a muscular, frame-bursting swagger. It feels almost baroque in its theatricality.

Quite a few pieces here come from his workshop, with the boss’s own hand in them still a matter of dispute. This Botticelli “factory” tried out themes and treatments with a hard-headed practicality. Forget any romantic notions about Botticelli’s supposed muse, Simonetta Vespucci. Here, she becomes the pretext for a group of portraits that morphs her angelic face and labyrinthine hair into a set of experimental variations. We also meet two full-size studio prototypes for the goddess in The Birth of Venus. Talk about letting daylight in on magic.

Warhol and his multiples come to mind: just as the curators intended. At the V&A, the afterlife contaminates the life. The artist’s kitsch offspring, with their hi-tech manipulations of an icon, reach back five centuries to deconsecrate the Botticelli shrine. We come to see the past through the eyes of the present. Those eyes reveal an artist more innovative, more resourceful, but less metaphysical, than Rossetti, Ruskin or Pater ever suspected. In this display, craft trumps soul.

You suspect that, at the V&A, design counts as the one true divinity. All the same, this part of the show does nod towards the intellectual and philosophical Botticelli. We see a book by the poet-translator Angelo Poliziano, one of the scholars at the Medici court whose work nourished the imagination of the artist. Above all, the V&A boasts five of his glorious brown ink-on-vellum illustrations of Dante’s Divine Comedy, probably commissioned by Lorenzo di Pierfrancesco de’ Medici in the 1480s. After marvelling at the grandeur of their vision and the tenderness of their execution, visitors should head straight across London to Somerset House. There, at the Courtauld Gallery and quite unnoticed in the V&A’s publicity material, 30 more of Botticelli’s Dante drawings are on show. They star in a selection from the 10th Duke of Hamilton’s fabled collection – bought by Berlin’s graphic-art museum in a famous coup in 1882.

The Dante drawings really are divine. Using the simplest of means, Botticelli leads us from the Inferno through Purgatory to Paradise. The artist dramatises, and humanises, the pains of hell or the joys of heaven with swift, subtle, even comic touches. The demon who rows Dante and his guide Virgil across the Styx turns to us with a merry smile. You next, mate! In Purgatory, vainglorious artists have to expiate their narcissism by bearing huge boulders up a hill. YBAs, take note. Does one of them have the artist’s own features? Some think so. And in Paradise, Dante’s beloved muse Beatrice gently smiles at the poet. Here the spine tingles. This Beatrice almost has the face of Venus from the Primavera. At the Courtauld, pure bliss beckons. Anyone who has waded through the purgatorial garbage that defaces Botticelli at the V&A deserves it.

‘Botticelli Reimagined’ continues at the Victoria & Albert Museum until 3 July; vam.ac.uk/botticelli. “Botticelli and Treasures from the Hamilton Collection” is at the Courtauld Gallery, Somerset House, London WC2 until 15 May; courtauld.ac.uk

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments