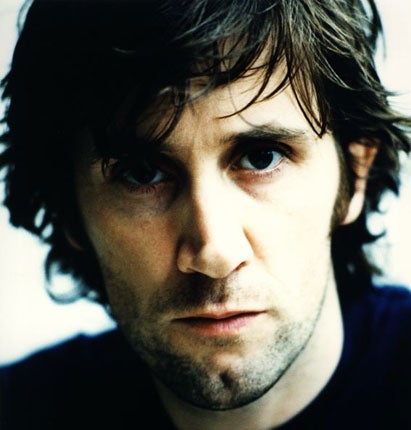

Angus Fairhurst: The forgotten man

While Damien Hirst and other YBAs went on to make millions, their friend Angus Fairhurst seems fated to be remembered for his suicide. Michael Glover visits the first retrospective of his work

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Just over a year ago, the artist Angus Fairhurst committed suicide in the most shocking of circumstances. He hanged himself in a wood on the last day of a solo show at the Sadie Coles Gallery in London.

Fairhurst, though less well known than the others, was among that generation of British artists, all trained at Goldsmiths in the 1980s, who came to be known as the YBAs. He took part in Frieze, their first group show, in 1988, and, more recently, he was still exhibiting with Lucas, Hirst and others in a show at Tate Britain with the silliest name imaginable: In-a-Gadda-da-Vida. That title was Hirst's idea. The show itself took place in 2004.

Now, for the first time since his death, we have an opportunity to examine in detail a large retrospective of his work, well displayed on all three floors of the handsomely refurbished Arnolfini in Bristol, and to ask ourselves whether he deserved the relative neglect.

As you walk around the show, it is difficult to stop yourself asking a couple of shamefully prurient questions, the kinds of questions which any art critic should perhaps not be asking, and which any human being (and art critics are usually both) simply can't stop themselves asking. Why did he do it? And: is it at all evident in the art that he might be about to do it?

When you walk into the ground-floor cinema space and stare up at the screen, you are confronted by the sight of a tall, slender man trying to fight his way out of a gorilla costume, squirming about, writhing and leaping, stamping on the pesky thing. At last he does it, and there he stands, heaving and panting from so much exertion – and entirely naked. This is Fairhurst himself, playing – playing?! – at being himself in his own film.

Fairhurst had something of a fetish about gorillas. They are all over the place in this show – in drawings, large-format photographs. He also did many gorilla cartoons. You can see these in a teensy gallery on the top floor. There are even giant gorilla sculptures, in bronze. One of them is armless. The arm lies on the floor like a bit of detritus from the street. A one-armed gorilla is staring down at it, bemusedly. Fairhurst even took a photograph of someone in a gorilla suit, seated on a sofa, cradling the artist himself, naked. Gorilla Pietà. You can see that on the second floor.

Now the gorilla, when he is allowed to survive at all, blunders through life. He is acutely intelligent, yet, visually, he is afflicted by the fact that he has all the high seriousness of a cartoon of himself. Fairhurst could not escape from gorillas. He made them, and he drew them again and again – they were so ridiculous, such figures of fun, always so incapable of escaping from the consequence of being themselves. He could not escape from this terrible yoking together of the serious and the unserious, the dignified with the idea of the tragically ridiculous.

Can this be linked up in some way with his terrible fate? This obsession with beastliness, the relationship between the human and the beast in man? The question hangs in the air, unanswerable.

Gorillas apart, there are two kinds of work in this show. One is collage, the layering of image upon image. This was hugely important to Fairhurst. He liked to take images – from a fashion shoot, for example – and then to cut them up and rework them until they seem to be offering us a kind of travesty of the super-cool messages of sex, bodily ease and prosperity that they once existed to proclaim. On the ground floor, he does this sort of thing on a grand scale. He is especially fond of cutting around the human figure, and then leaving out the figure itself, so that the work becomes a statement about absence, about the fact that we have this immense superstructure of visual seduction, but at its heart, there is no one there. The human has absented itself. Hollow vessels.

One entire series of paintings – they are collectively entitled Underdone/Overdone – consists of images of a clearing in a wood. Fairhurst separates the colours, and then overlays the images, one upon another, until what was at first recognisable as a group of trees is finally transformed into a dense and unreadable mesh of signs. The result is very disturbing psychologically. We think we have entered something relatively benign, something we understand, and, little by little, we come to understand it less and less. We find ourselves horribly trapped inside a space which feels like the very embodiment of unreason.

There I go again! This was supposed to be dispassionate art criticism, and not a crude, quasi-psychological reading of a human being on the verge of some tragic abyss. Well, the sad fact is that there is no final way of telling why he did it, yet it is undeniably true that while other YBAs became shockingly famous and absurdly rich – due, in part, to their brilliant ability to promote themselves – Fairhurst was not in that same league at all. He didn't have the wherewithal to put himself about. He may not even have wanted to do such a thing. Fairhurst, in short, was the partially forgotten one.

And now this large-scale show gives Fairhurst a posthumous opportunity to demonstrate to us that the world is indeed an unfair place, that his talent was at least equal to that of the others, and that customers for art – God blast their blinkered, craven ways! – are so many dumb sheep that follow when chance, good luck, a smattering of glitz and bling – and, oh yes, a modicum of talent – come together.

But does he deserve it? Is he really as good – or even better – than Lucas and Hirst? Or did he merit instead that relative obscurity? Well, sadly, there is nothing in this show which makes it evident to us that Fairhurst was indeed a major talent.

Angus Fairhurst at Arnolfini, Bristol, until 29 March

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments