A Continuous Line: Ben Nicholson in England, Abbot Hall, Kendal

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The first wife of the painter Ben Nicholson, Winifred Nicholson, summed up the utopian beliefs of British modernism when she wrote: "To say a thing was modern was to say it was 'good', sweeping away Victorian, Edwardian, Old Theology, Old Tory views. In the new world there would be no slums, no unnecessary palm trees, no false ornament – but clarity, white walls, simplicity."

Ben Nicholson has long been recognised as one of the leading exponents of British modernism, and this delightful exhibition underlines the importance of his role. The son of the celebrated Edwardian painter William Nicholson, Ben made his reputation by absorbing what was essentially a European abstraction – influenced by artists such as Piet Mondrian and Naum Gabo – into English art. His white reliefs, first produced in 1934 and continued into the Forties, represent the high point. Emptied of all extraneous detail and colour, whiteness stood for what was pure, modern and spiritual. In a period of political turmoil, they offered a new way of thinking about the world and Englishness.

Of particular interest in this exhibition is the emphasis on the lesser-known periods of Nicholson's art, which reveal the fluidity between his faux-naïf representation and abstraction. British abstraction was never as intellectually assertive as its European counterpart, or as muscular as it was to become in America. Here, it had a good deal to do with throwing off the constraints and dark palette of 19th-century academic painting. It embraced light and freedom in opposition to Victorian constraints with its obvious class values.

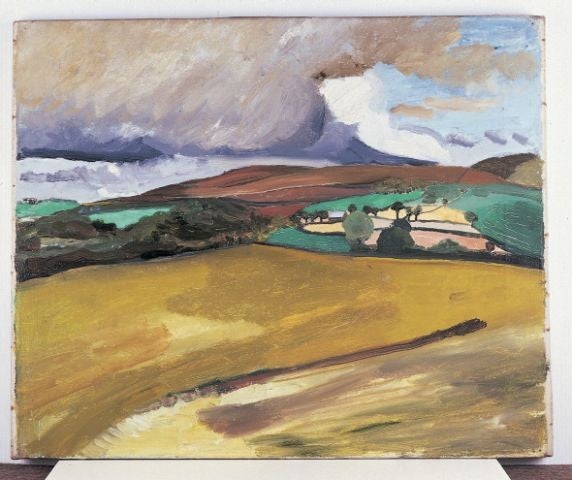

Many of the early works on show here were painted in Cumbria, and these small landscapes have a whimsical, idealised Englishness. Nicholson was attracted to peripheral places – such as Cumbria and later Cornwall – that had an undiluted poetic intimacy. Simplicity was what mattered to him. This was, no doubt, a reaction against the Edwardian art of his father, but also an expression of his own Christian Science beliefs – the mind, body, spirit philosophy of his day. There is a sweetness to his rolling hills with their whitewashed farms and clunky horses that float within the picture plane without any sense of scale or perspective.

Much of this apparent innocence was the result of his meeting with the self- taught painter-fisherman Alfred Wallis, whose "untrained and innocent depictions" of Cornish fishing life, along with his use of "lovely dark browns, shiny blacks, fierce greys and strange whites, and a particularly pungent Cornish green", had a profound effect on Nicholson and other British modernists. Nicholson's white horses in Cumbrian fields were soon to be replaced by plucky little barques seen from cottage windows in Mousehole or St Ives. Where Picasso turned to the African mask to find primitive authenticity, Nicholson looked to a Cornish fisherman.

Nicholson's work changed when he left Winifred for the sculptor Barbara Hepworth. The three-dimensional object became more important, and culminated in his first carved reliefs, whose textured surfaces evoked something of simple rural craftsmanship.

During the war, he and Hepworth settled in St Ives. In the Thirties, he had appropriated a more Cubist approach, perhaps due to his relationship with Hepworth, but by the Forties he was again making still lifes based on objects placed in windows. These suggested the tension between two places: between outside and inside, and between the domestic and nature. Less to do with the early Cubism of Picasso and Braque, and more to do with the liberty of appropriation, Nicholson developed his own version of Cubism. The jugs and mugs with question-mark handles on window ledges remained, but set within new spatial frameworks.

Not only does this exhibition emphasise the lyrical nature of British abstraction, but it charts its gradual shift away from representation to reveal something of the new spirit of the early post-war years.

To 20 September (01539 722464)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments