Pont: The British Character (1936)

Cartoons are generally a critic-free zone. They're designed to speak for themselves, and most people can get the point without assistance. All the critic can do, it seems, is analyse the joke to death. But let's not be deterred. Let's take a great cartoon, and see what can be done. This year it's the birth-centenary of the cartoonist Pont, who flourished in Punch in the 1930s. There's a show of his work at the Cartoon Museum in London.

Pont worked mainly in series, doing variations on a theme. The most popular was The British Character, acutely imagined illustrations of national foibles. You have Importance of Not Being Intellectual and A Weakness for Oak Beams and Strong Tendency to Become Doggy, among many others.

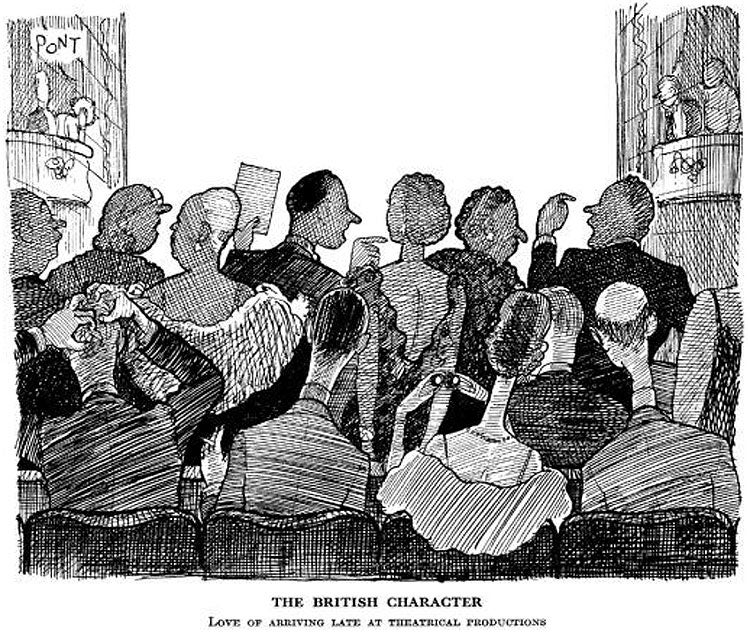

One of the series stands out – Love of Arriving Late at Theatrical Productions. It's a nice title, but the image hardly needs any caption. It's pure visual comedy, and a very strong picture – strong enough to take analysis.

The comic situation portrayed is obvious, of course. You need no telling what's happening or what's funny. But don't take that for granted. The situation is only obvious because the cartoon is a masterpiece of composition.

Consider the problem the cartoonist sets himself. There are 13 figures in this confined space. They form three distinct lines or layers, each with its distinct pattern of behaviour – the barging latecomers, the forbearing standers, and the sitters whose view is blocked – but these layers of figures are all overlapping.

The action of the scene is complex and interactive, everyone reacting to everyone else, and each figure differently. The people are mostly viewed from the back, and depicted in a dim and narrow range of tones (it's a darkened auditorium). And with all this, every detail of their behaviour, collective and individual, must be made clear.

And it is – miraculously clear. The three overlapping lines stay distinct. None of the figures merges with another. We pick up every clue. Which of the Old Masters, with all their experience of dense multi-figure scenes, could have handled this subject with Pont's effortless clarity? Caravaggio? Poussin?

The clarity is actually part of the comedy. The cartoon is funny not simply because it depicts, vividly and observantly, a familiar awkward situation. It's funny because it takes a situation that's visually and physically very muddled, and reveals it so legibly.

We can see exactly what's going on, though the people involved can't. We get a wonderfully perspicuous view of somebody else's confusion. We have the pleasure of extracting sense from jumble – just as we have the pleasure of reading body language from bodies seen from behind and in near-silhouette. The artist, through his powers of organisation, affords us these pleasures.

He gives us others. There's the energy and cross-rhythms of his shading. There's the counterpoint between the jostling heads. There's the way the latecomers are moving, left to right, straight through the space of the picture. There's the stage, the ultimate object of everyone's interest, represented as an area of blank light.

And now we can settle down and enjoy Pont's drama of stance and gesture and character and emotion, about which a critic need add very little. But don't overlook a subdued joke, lurking half-hidden in the scene: the man who refuses to stand.

The artist

Pont (1908-1940) was the pseudonym of Graham Laidler, derived from a nickname – Pontifex Maximus – he acquired during a visit to Rome. He came from Newcastle upon Tyne and trained as an architect, but by his mid-twenties had become one of Punch's star cartoonists. He worked in sequences – At Home, The British Character, Popular Misconceptions. His images were packed with real and surreal observations. "Pont Clubs" were formed to study them. Extraordinarily productive, Laidler suffered from TB, and mostly lived abroad. He died aged 32. Pont: Observing the British continues at the Cartoon Museum, 35 Little Russell Street, WC1, until 27 July. A well-illustrated catalogue is available.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

3Comments