Zaha Hadid’s modernist library inspires shock and awe in Oxford

A new £11m library and archive building for the Middle East Centre at St Antony’s College has been called a 'beached whale' and a 'giant ear trumpet'

Your support helps us to tell the story

This election is still a dead heat, according to most polls. In a fight with such wafer-thin margins, we need reporters on the ground talking to the people Trump and Harris are courting. Your support allows us to keep sending journalists to the story.

The Independent is trusted by 27 million Americans from across the entire political spectrum every month. Unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock you out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. But quality journalism must still be paid for.

Help us keep bring these critical stories to light. Your support makes all the difference.

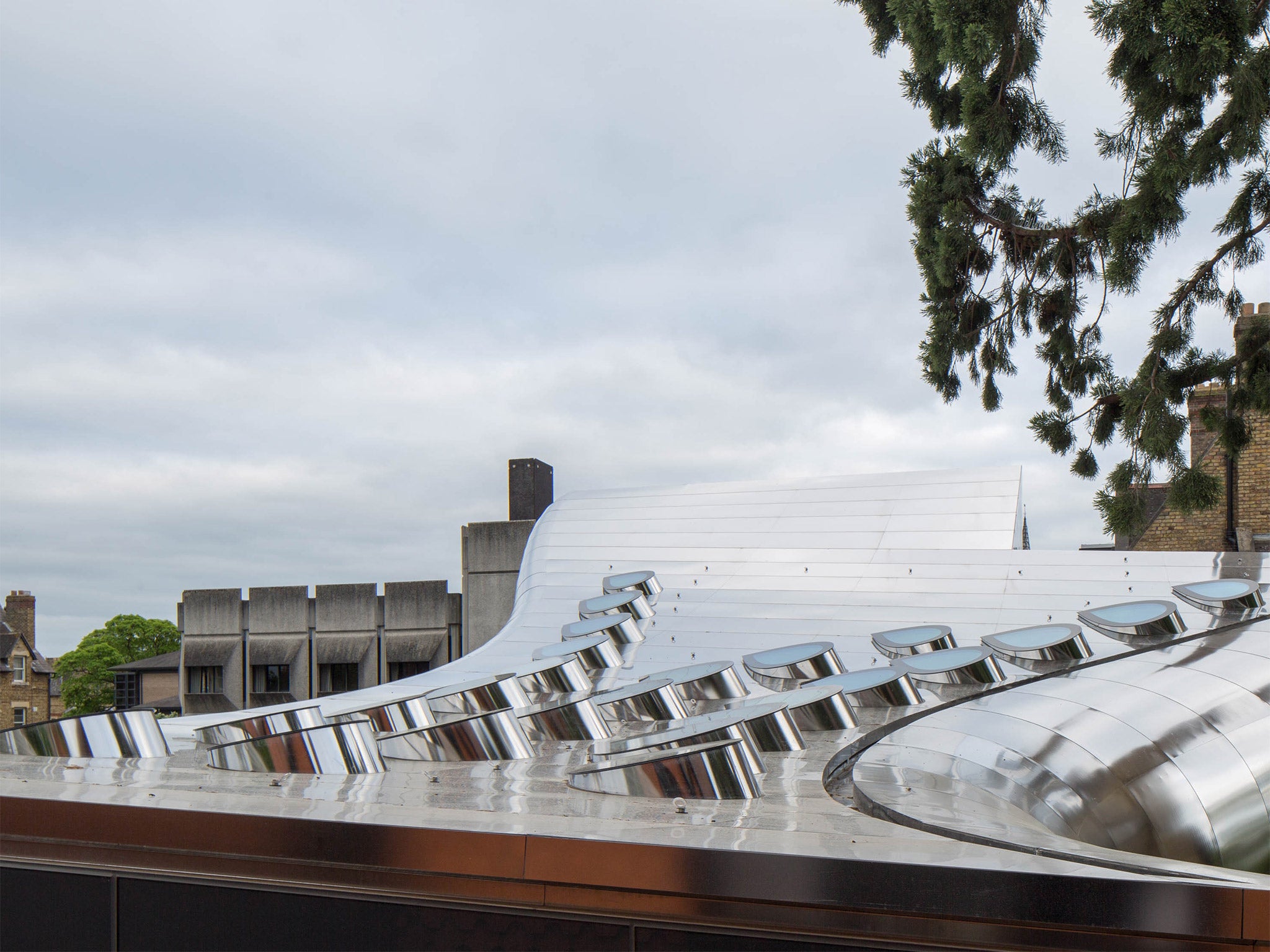

In Oxford, the city of dreaming spires, any attempt to introduce shock-of-the-new architecture triggers dogfights between trads and mods. And so it was no surprise that when Zaha Hadid produced her sinuous steel-clad design for the new £11m library and archive building for the Middle East Centre at St Antony’s College, it was attacked. “Looks like a beached whale,” fumed one objector. “A giant ear trumpet,” said another. “No, a crashed airplane” – and so on.

Seen from Woodstock Road – calm, leafy, classic Inspector Morse territory – the steel form lolls like a glinting chrysalis between the centre’s two original 19th-century buildings. The centre’s south end, facing the college’s main buildings, flares out like a vast TV screen overlooking the garden.

Oxford’s planners were split down the middle over Hadid’s proposal. Those in favour argued that its design quality, and the centre’s desperate need for more library, archive and lecture space, overcame the statutory need to fit in with the Victorian buildings and green spaces in the conservation area around it. It took the chairman’s casting vote for the council to pass the design.

Hadid’s building is the most radically designed modern college building in Oxford since the love-it-or-hate-it cliff face of James Stirling’s Florey building at Queen’s College. This is undoubtedly Hadid’s most intriguing small building, one that she originally described as “a soft bridge”. And the closer you get to it, the softer it looks, the sky and trees wavering in reflections across its steel skin.

Other things are being expressed, too. Zaha Hadid’s late brother, Foulath, a Fellow of St Antony’s, was “a huge advocate for this building”, according to the centre’s director, Eugene Rogan. The design reflects an early conversation between Rogan and Hadid. “I said I thought of it like a Picasso,” he recalled. “There were paintings that were not just Picassos, but Picasso’s Picassos. I asked Zaha to design a building that would be a Zaha’s Zaha. She liked that.”

And she also liked the fact that one of her architectural heroes, Brazilian modernist Oscar Niemeyer, had designed a building for St Antony’s in the 1960s. He offered his design free, provided the project was built. It wasn’t, so he got his fee. Rogan has kept Niemeyer’s yellowing drawings safe, and they show a long, low building with big porthole windows.

Hadid did not have to compete for the commission for the new building, which was paid for by a single donor, Investcorp. St Antony’s had invited her to lecture at the college in 2003. Rogan studied her architectural drawings for the four-level, 1,200 square metre centre closely: “Every line meant something. It bends the brain. I’m in love with this building and I can’t hide it.”

He likens the architecture’s silvery swerve to a melting dumbbell, “and there’s something Daliesque about it”.

But this wasn’t just a case of blue-sky creativity. The building’s unusual shape was dictated by a century-old sequoia tree, and its root system, in the middle of the rectangular site. Furthermore, the maximum height of the four-level building had to align with an eaves gutter on the old vicarage.

The building’s asymmetrical metal shell is the money-shot, and its 25 projecting oval rooflights must be a nod to Niemeyer’s portholes. But the most remarkable thing about the building is its interior. Here, the high-tech vibe of the steel shell gives way to a series of beautifully crafted interiors – a huge design and construction challenge, given that most of the wall surfaces are curved.

The double-ellipse staircase, the cocoon curves of the library, and the absence of any obvious structural “grunt” or fidgety details give the interiors a flowing marshmallow soft quality which is, in places, so gracefully composed that even Disgusted of Oxford might pause in mid-harrumph.

Shock of the new oxford developments

The Florey building, Queen’s College

James Stirling, one of British architecture’s most brilliant mavericks, designed the Florey in the late 1960s, and it is the strangest and most radical piece of modern architecture in Oxford. The students’ rooms are in the propped angular cliff facets, and the common areas are in the podium. The building is currently being modernised.

St Catherine’s College

Designed by a Dane, Arne Jacobsen, and completed in 1964, this was the first modernist college in the city. Most architects are in awe of its bold combination of concrete, timber, bronze and brick. The architectural historian, Nikolaus Pevsner, described St Catherine’s as “perfect”. But one student said it was like being in a borstal.

Keble College extension

This 1979 building was designed by Ahrends, Burton and Koralek, who later infuriated the Prince of Wales with their “carbuncle” scheme to extend the National Gallery. The Keble extension’s brick segment segues into a smoked-glass façade whose slanted elements have a reptilian glint. Students complained that rooms were either too dark or too hot.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments