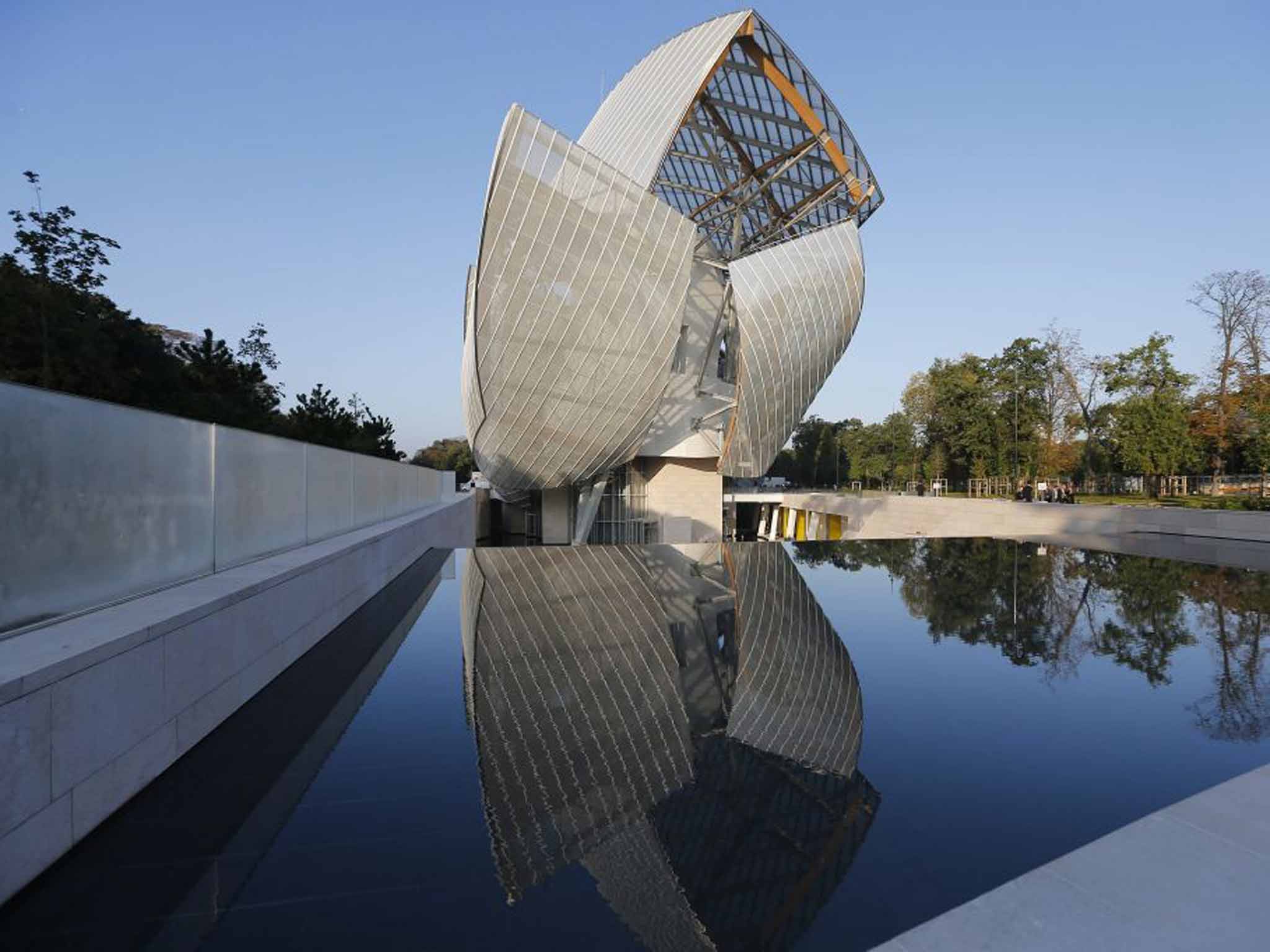

Frank Gehry's new Paris mega gallery

The gallery opens next week. Its architect, Frank Gehry, tells Jay Merrick how the death of a daughter inspired its floating form

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Can a building be described as crazy and tender? It can when the legendary architect Frank Gehry is talking about the new Fondation Louis Vuitton in the Jardin d'Acclimatation in Paris. It's crazy in its structural complexity. And tender in the way the 85-year-old Canadian-American cites Michelangelo to explain the 12 huge curves of glass that billow around the core of the building like vast sails, or translucent fish scales.

Above and around him, hundreds of steel beams, metre-thick segments of laminated timber, and metal joints that could hold bridges up, veer and vector, connecting the concrete, iceberg-like core of the building's 11 galleries with the outer layer of glass sails.

This is the biggest privately funded arts project in Paris for decades, a true grand projet in the French tradition. But, says, Gehry, "you have to keep things not precious. You have to keep that sketch quality. Anything overly finished is static to me. It's not living. It's not open to interpretation. We made the building ephemeral, like a big sculpture. It's floating and changing. It looks like it's growing. No matter what you do with a normal building, it's a static building. This one isn't."

Gehry says he "freaked" when he thought about the cultural importance of the land around the site. "Marcel Proust must have been here. The Bois de Boulogne is a holy place. You can't just plunk something into it. To make a building of ephemeral qualities was a given."

The Fondation's carapace of sails shimmers with delicately distorted reflections of the surrounding trees. The core of the building is anchored in a grotto of water, and its glass prow juts over a stepped cascade of water. The ship metaphor is fine, but there's a more tempting one – the mystical white whale that haunted Captain Ahab in Herman Melville's Moby-Dick.

Like Ishmael, Moby-Dick's narrator, Frank Gehry is a compulsive questioner of certainties, and he has produced a building that comes together as if it's also just about to fall apart. To borrow Ishmael's words, Gehry promises "nothing complete, because any human thing supposed to be complete must, for that very reason, be faulty."

The Fondation's collage-like architecture is in the Cubist or Constructivist arts traditions. But Gehry's art influences go back much further than early 20th-century Modernism. "Nature made the face," he muses. "Man made the clothes. Michelangelo studied the folds. He spent a hell of a lot of time on painting the clothes and the folds. When you're a baby in your mother's arms, you're in the folds."

You won't encounter a more beguiling justification for avoiding right angles, and repetition, in architecture. Each structural element of the Fondation Louis Vuitton, and every piece of glass, is a one-off.

But there is also a subtly personal humanity in Gehry's remark. "I lived in Paris in 1960 and brought my little girls here." He gently adds that one of his daughters died just as he began work on the design of the Fondation Louis Vuitton, more than seven years ago.

He always says that the client is the key to any successful architectural project. Bernard Arnault, whose corporation owns Louis Vuitton, was one of them. In a design process thronged with scribble-like drawings and a stream of hand-made models resembling rucked-up amoeba that have swallowed building blocks, Gehry eventually produced four option models of potential building forms.

"Whenever I tried to make the model more architecturally efficient, Bernard would say: 'No, Frank, do this one, it seduces me!' It wasn't a deliberately extravagant building. But as soon as you have a double skin, it gets extravagant." Louis Vuitton hasn't revealed the cost of the building, but $143m has been bandied about.

The building's strange beauty was too strange for a determined regiment of objectors who nearly derailed the project. At the height of the row, the normally benign Gehry reportedly described them as uncouth philistines.

France's own superstar architect, Jean Nouvel, backed Gehry and said of the objectors: "With their little tight-fitting suits, they want to put Paris in formalin. It's quite pathetic." The government cleared the design on the dubious grounds that the building, in a protected green environment, was a one-storey structure.

The Fondation's giddy geometry is hard to resist. It has created a building with no clear sense of inside and outside. Some of the views from it are superb. There are 3,500 square metres of galleries, and some have an unexpectedly chapel-like atmosphere. One is 70 metres high, and Thomas Schütte's 30m statue Mann im Matsch (The Diviner) looks almost dinky in it. Welcome to Paris's new arts fun palace.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments