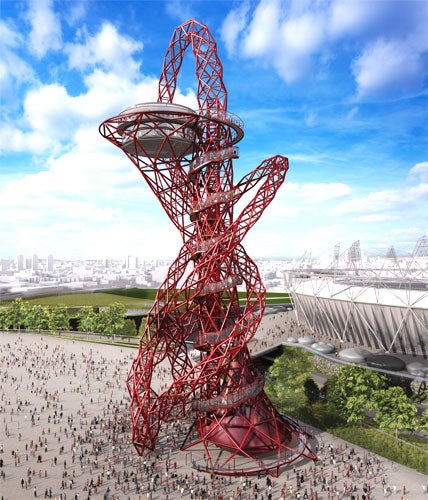

120m high and very, very red: the best seat at the Olympic Games

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The capital's own version of the Eiffel Tower, 120 metres high and visible from outside London, has been chosen as the monument to mark and tower over the 2012 Olympic Games.

The tall, looping tower on the 2012 Olympic site, designed by Anish Kapoor and Cecil Balmond, will be Britain's largest ever public artwork. Boris Johnson, the mayor of London, says it will be a brilliant totem of post-Olympic urban regeneration in Docklands, and one that would have "boggled the minds" of the Romans, and of Gustave Eiffel, whose own tower he so admires.

Johnson's Tower of Boggle spawns other boggles. The potential cost of the structure, for example, would have been politically disastrous if the billionaire Indian steel magnate Lakshmi Mittal had not agreed to supply 1,400 tons of metal free, equivalent to £16m of the total £19m cost (the rest comes from the London Development Agency).

Kapoor and Balmond beat design teams led by Antony Gormley and architects Caruso St John. In engineering terms, the Orbit Tower has no clear-cut precedent; nor does it bear any of Kapoor's hallmarks. Its sculptural power lies in its ability to suggest an unfinished form in the process of becoming something else. It is strange, it is not an eye-con, and there is something artistically risky about it.

And this is the blood-red structure's essential virtue. In the last half century, the public art movement has too often pockmarked Britain's towns and cities with banal artworks – turds in the plaza, as the architect James Wines put it – that fail to engage the eye, the heart, or the mind.

There's something beautifully fractious, and not quite knowable, about the ArcelorMittal Orbit tower's design. It's anti-bling, and its brusque form will be either loved or hated.

The decision to build the tower was decided in moments, and in true power-broker style. "Had I not bumped into Lakshmi Mittal, for the first time, in a Davos cloakroom, we would not be where we are today," Johnson recalled. "Our conversation took about 45 seconds. I explained the idea, which took 40 seconds. 'Great. I'll give you the steel,' he said, and that was it."

Johnson, it should be noted, is not the avatar of monumental ambition in the capital. Nicky Gavron, Ken Livingstone's deputy mayor, told me during a party thrown by the architect Sir Terry Farrell some years ago of her vision to move Marble Arch to the western end of Oxford Street – "like the Arc de Triomphe." Just imagine the power-conversation she might have had.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments