She may not have known it, but even Thatcher was not immune to art's capacity to challenge

Plus: The BBC should regret the passing of The Hour and Hytner's first-class

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Here are two anecdotes. They were told to me by two big figures from the Eighties arts scene, one of them a giant figure, concerning Margaret Thatcher's engagement with the arts, when she was Prime Minister. They are not an analysis of policy, they are not a discussion of cuts, though her premiership and the appointment of William Rees-Mogg as chairman of the Arts Council for most of that time ushered in an age of severe cuts in the arts, an era that saw both the National Theatre and the Royal Shakespeare Company closing parts of their operations for a time. No, they are simply anecdotes that reveal a distinctive way of approaching the arts.

The first was told to me by Sir Peter Hall. When he was head of the National Theatre, he staged the premiere of Peter Shaffer's brilliant play Amadeus in which Simon Callow portrayed the youthful Mozart as a particularly foul-mouthed, scatological young genius. Mrs Thatcher, as she then was, came to see it, and Sir Peter entertained her to dinner afterwards. She did not look happy.

"I think it is disgraceful that the National Theatre shows Mozart uttering such obscenities, Mr Hall," she said, ignoring his knighthood, "a composer of such elegant and wonderful music".

"But Prime Minister," he protested, "it is actual fact that he did talk like that. He used four-letter words."

"It is not possible," she responded, "not from someone who could create works of such beauty."

"But Prime Minister, I can assure you that this was the case. Mozart's own letters confirm it."

"Mr Hall," she asserted with finality, "I don't think you heard what I said. IT COULD NOT BE!"

And that was that. It ranks for me alongside another conversation, one related to me by Julian Spalding, the former director of Glasgow Museums, about the time he showed her round. She mentioned the record price paid at auction for a celebrated work by Van Gogh. "Isn't it remarkable, Mr Spalding," she said, "the amount of money that was paid for Van Gogh's 'Chrysanthemums'."

"Sunflowers, Prime Minister," he gently corrected her.

"And, do you know, Mr Spalding," she continued, ignoring the interruption, "they weren't even his best chrysanthemums!"

Perhaps her general lack of engagement with the arts was a result of the certainty in her own opinions that those stories, particularly the first one, display, and the difficulty that can occur when the arts shatter certainty – even if they did provide moments to treasure.

Hytner will leave a first-class legacy

Sir Nicholas Hytner's announcement this week that he is leaving his post of artistic director of the National Theatre (though happily not for a couple of years yet) is bad news for the arts. He may have done his decade of service by which directorships for no very good reason tend to be measured, but there is no sign of the innovation and excellence that has characterised his time there fading.

Indeed, only last night a new venue at the National had its official opening. The Shed adds, not just to a startling consistency of acclaimed productions, improvements to the main buildings, but also his agreement with Travelex to provide cheap seats (that he was kind enough to tell me owed a little to my own arguments on these pages for cheaper theatre tickets), the introduction of live cinema broadcasts of plays, and his getting the unions to agree to Sunday performances. One can imagine that his distinctive blend of immense charm and firm determination counted for a lot there.

It has always been hard to imagine that anything could equal the electric excitement of the early National Theatre years under Olivier but the Hytner era has come pretty close.

BBC should regret the passing of The Hour

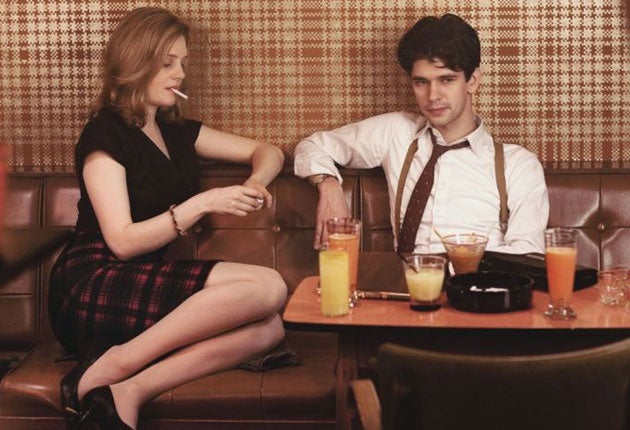

I see that The Hour features in the Bafta nominations announced last Tuesday. This time Peter Capaldi is up for best supporting actor. The latest series of the BBC drama achieved a rare feat, a second series that was even better than the excellent first. It had, of course, a cast to die for with Ben Whishaw, Dominic West, Anna Chancellor, Romola Garai and Capaldi, as well as a script by Abi Morgan.

But despite past Bafta, Emmy and Golden Globe nominations for the taut, tense drama set in the BBC itself and in Soho in the Fifties, the BBC decided to axe it because of lower than expected ratings. This week's Bafta nomination should make the BBC think again. Ratings aren't everything. This was a class act.

d.lister@independent.co.uk

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments