Britain has taken longer to recover from recession than at any time since the South Sea Bubble

The Coalition’s triumphalism over restoring output to its starting level is totally misplaced

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.I have to admit I was wrong in claiming that the recovery that has occurred under the Coalition is the slowest and worst in one hundred years. I should have said worst in 314 years. I severely understated how bad things have actually been. The editor of The Spectator, Fraser Nelson, pointed out to me that I hadn’t studied historical precedent adequately and was severely understating how bad the recession really has been.

It is without historical precedent. Fraser pointed me to a series published by the Bank of England which provides data on real GDP back to 1700, and guess what? He was right. It is now clear that George Osborne is responsible for the worst recovery in three hundred years of recorded history. Celebrate? I don’t think so.

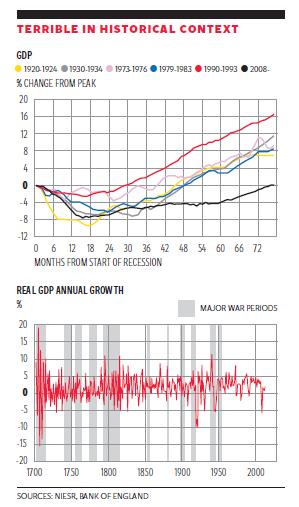

So let’s look at the data starting with the 20th century, and then we will look at the 19th and 18th centuries as well as other countries. The first chart shows the length of time it takes in months to restore lost output in the six main recessions of the 20th century: 1920-24, 1930-34, 1973-76, 1979-83, 1990-93 and 2008-2014.

First, all previous recessions’ lost output was restored in four years or less, in contrast with just over six years – in fact 76 months according to the National Institute of Economic and Social Research – for the current recession. Second, it is apparent that the steepness of the path of recovery in all previous recessions was approximately the same, that is to say, the slopes of all the upward lines pre-2008 is approximately the same. Third, the recovery under Labour between Q32009 and Q32010 also broadly followed that same path, as does the current recovery over the last year or so.

Finally, what is unprecedented is the flatlining of the economy in the Great Recession under the Coalition, once the recovery was already underway, from around months 37 (February 2011) through month 59 (December 2012). In February 2011 GDP was 4.9 per cent below the starting level; it was 4.2 per cent below it in January 2012 and still 4.2 per cent below in December 2012. It had still only reached minus 3.1 per cent by May 2013, in month 64. The Coalition killed off recovery at birth.

This puts the triumphal claims of the Coalition about the success of their policies in context. No previous macroeconomic policies for three centuries have been so disastrous. The Coalition inherited an economy that was growing nicely and through their misguided austerity sucked the lifeblood out of the UK economy by their misplaced desire to reduce the size of the state. If we extrapolate the growth line under Labour policies on the chart forward to see where it cuts the vertical axis, it cuts around 48 months rather than the actual 76 months. Some have even claimed that the Coalition’s policies were a success because they avoided a double-dip. Interestingly this depends on three quarters of GDP data from Q42011 to Q22012 of minus 0.1 per cent, 0.0 per cent and minus 0.4 per cent. The argument is a weak one given that if exactly the same drop in output had been in a different order, minus 0.1 per cent, minus 0.4 per cent and 0 per cent, that would constitute a technical double-dip. In any case the zero will probably eventually be revised downwards to a negative anyway. So pretty thin gruel.

We do know that the situation in other G7 countries was quite unlike the UK, which is next to last, behind Italy, in restoring output. Indeed, Canada restored its peak within two years, while the US, France and Germany restored theirs within three years. There was no comparable flatlining in France, which presumably was more impacted by eurozone weakness than the UK. If we examine GDP per head, the situation is even worse; it remains around 5 per cent below its starting level in the UK and looks unlikely to recover lost ground for another couple of years. GDP per capita is above starting levels in Germany, Japan, Canada, the United States and France.

David Smith in The Sunday Times on 27 July even suggested that to make things look better for the Coalition we should calculate GDP per capita by dividing by the 16-64 population, which has grown half as fast as the overall population or the 16+ population because “babies and children do not contribute much to economic output”. But he forgets that those age 65 and older increasingly do. Employment of those aged 65 and older is up 67 per cent since January 2008 and their overall numbers are up 15 per cent. Oh dear, if you don’t like the answer try massaging the data! The likelihood also is that the revisions to GDP that are coming in September will alter the level of GDP rather than the growth path. They are also unlikely to improve the UK’s relative performance as the changes are being made to other country’s estimates also.

The second chart plots updated data from a Bank of England article by Hills and Thomas on GDP growth over the period 1700-2013, with major wars marked in grey. It shows that the UK economy has, almost always, bounced back rapidly from peacetime recessions, without a two-year flatlining period. Wars are different. Ryland Thomas from the Bank of England has kindly pointed out to me that over the last three hundred years you can find one peacetime episode where it does take output over seven years (on an annual basis) to recover to its pre-crisis peak. This is following the South Sea Bubble in 1720. Then the next one of comparable duration is Mr Osborne’s three hundred years later.

No other Chancellor since records were kept has been so incompetent in extending a recession for so long. It isn’t that the depth of the shock was unprecedented. So the triumphalism over restoring output to its starting level is totally misplaced, especially given that the economy was growing along the typical growth path of 20th-century recoveries when the Coalition inherited it in 2010. I do recall saying in June 2010 “this Budget will kill the recovery stone dead”. And it did. Not since the South Sea Bubble in 1720 has Britain seen such a prolonged recovery.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments