The Mons Memorial Museum, Belgium: A tribute to the fallen and the future

The Mons Memorial Museum, documenting war’s human toll, opens this weekend. Simon Calder explores its poignant collection

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.To understand why a united Europe isn’t such a bad idea, take a Eurostar train to Lille and onwards to Brussels. In a high-speed blur, you will cross both the Franco-Belgian border and the line of the Western Front – a century ago, the bloodiest, most miserable corridor of conflict in the world.

Change trains at Brussels Midi for the swift southbound journey to a city perched handsomely, with a certain military bearing, on a hill. Mons was where, from our perspective, the First World War began and ended.

At the start of the brief, bloody Battle of Mons on 21 August 1914, 17-year-old Private John Parr became the first British soldier to die in the First World War. And 90 minutes before the armistice came into effect on 11 November 1918, Private George Ellison died on patrol on the outskirts of the city – the last Tommy to perish.

A generation later, many more young men were to die for their countries among the gentle rises and valleys that ripple out from Mons – a city that has long been an unwilling venue for warfare. And this weekend, the Mons Memorial Museum opens its doors to help us understand the causes and effects of conflict.

Ten million euros has been spent to transform a former pumping station on the southern edge of the city centre into a temple of peace, love and understanding; well, let’s hope that is what it becomes. Glass and steel lightens the old red brick, while white cubes help to create what the architects call “a stepping stone to the past”.

The exhibits begin with forgotten struggles, such as the 1794 Battle of Jemappes, that you may know only from modern-day street names, with contemporary portraits of generals in their be-medalled pomp. But hi-tech soon intervenes to shine a light on the region’s dark past, with plasma screens depicting the shifting military geography of Europe – a map stained with blood.

The Great War, as it was known when no repeat could be contemplated, was – like so many conflicts – played out on the plains of Belgium. West of Mons, the Western Front was home to a generation of young men who, if they were lucky, might escape with trench foot and lice infestations. But many were unlucky – hapless young men in as wrong a place at as wrong a time as it is possible to imagine, dying in their hundreds of thousands as they battled to redraw the lines along which Europe is fractured.

Captain Bloem of the 12th Prussian Grenadiers writes: “Wherever I looked, to the right and to the left: almost all just dead and bloodstained, the wounded twitching and groaning.” He deplored the British and their “experience from a dozen colonial wars – presumably with the butchers of the Boer among them”.

The First World War had been going on for more than a year before both sides figured out that giving soldiers steel helmets would at least temper the death toll. But they offered little protection against the industrial-scale slaughter of the machine gun, and none at all against mustard gas.

The clock on the tall, Baroque belfry of Mons was just two minutes from 11am on 11/11/18 when the final victim – a Canadian soldier – was shot on the edge of the city. By this time the Great Powers had fought themselves to a standstill.

The tower stood like a beacon warning the world of the slaughter it had witnessed. But after two decades of imperfect peace, Belgium quickly fell in the Second World War. Mons became a garrison town for the occupying Nazi forces, and civilians had to coexist with the enemy.

Guillaume Blondeau, the museum’s curator, says he set out to humanise the story of war.

“We have a parallel path between the soldier in the trench and the civilian here in Mons,” he told me.

“The people here created relations with the German soldiers, and so we speak about all their life, but also about the resistance, the patriots, the people that chose to react.”

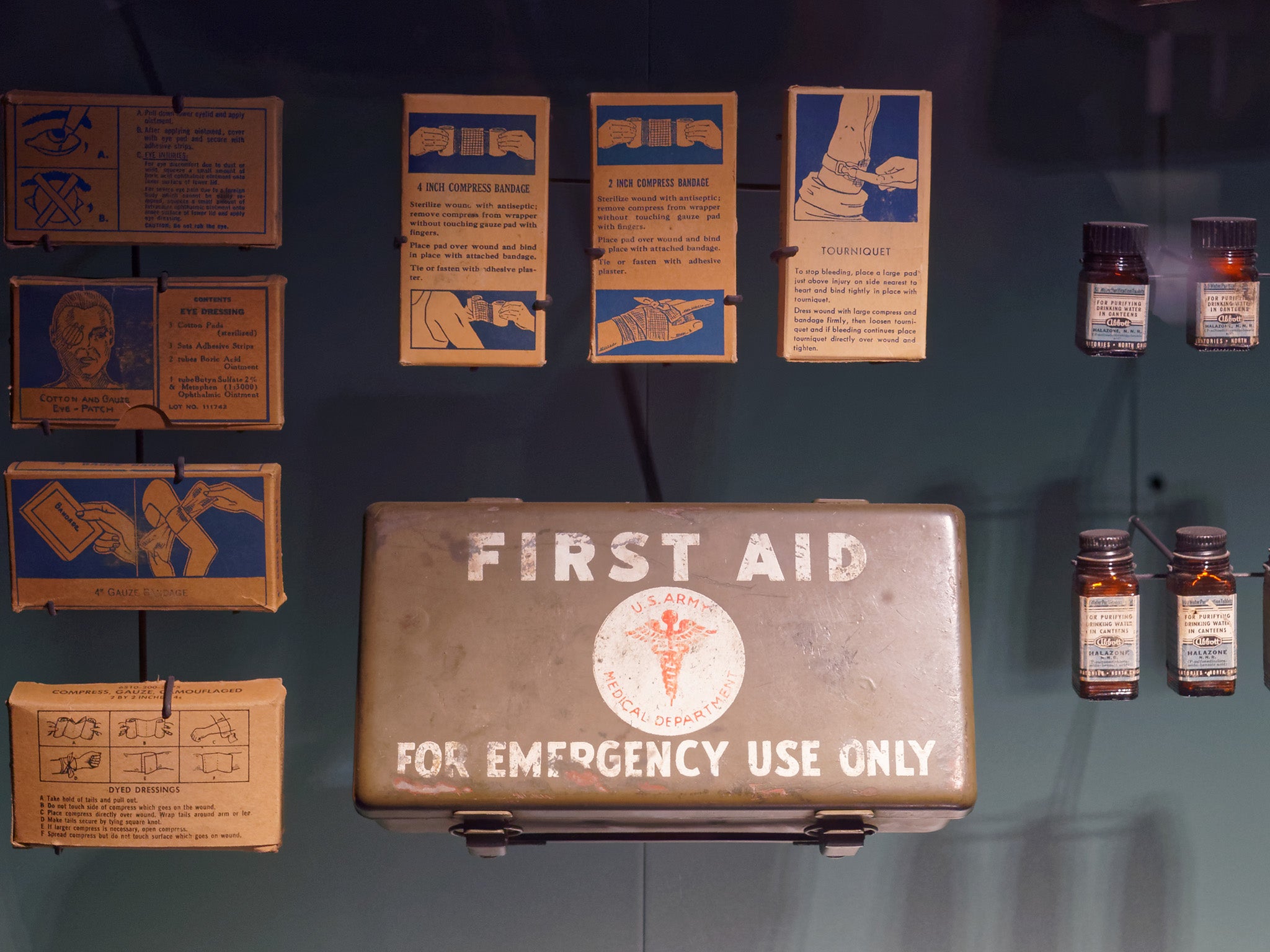

Relics of hope, glory and suffering, from marching drums to gas masks, are on display in their hundreds. But how to summon up the ghosts of distant generations slain by political pig-headedness? With grainy black-and-white faces peering out from flickering films; chilling footage from Germany’s Bundesarchiv, all smiles and swastikas; and a shattered doll amid the wreckage of a bombed family home.

Telling the story of the two 20th-century wars that engulfed the world is fraught. Humour is a rare relief: one J Murphy was a Royal New Zealand Air Force paratrooper who writes entertainingly about making a less-than-perfect landing behind enemy lines on a barbed wire fence, and his subsequent search for locals to whom he could entrust his life.

Memory is fragile, but in the Mons Memorial Museum the grainy black-and-white photographs of faces wreathed in grief remind the world of the madness that can engulf it.

Every visitor will arrive with their own preconceptions and preoccupations. I felt the exhibits rather hurried to a conclusion after the Second World War liberation of Mons, and left the visitor with a vague sense of “… and they all lived happily ever after” rather than going on to explore the repercussions: the horrors of the Cold War and the Iron Curtain, the late 20th century’s answer to the Western Front.

War is a journey that begins in hope but often ends far from the anticipated conclusion. Some people’s faith in human nature may be wounded by the Mons Memorial Museum, but the optimist will leave with the hope that humanity can transcend the industry of conflict.

Getting there

A rail ticket on Eurostar (0843 218 6186; eurostar.com) from London to Mons, via Brussels, costs £79 return. From elsewhere in the UK, the quickest approach is to fly to Brussels – from which trains run to Mons in 71 minutes, fare €17.20.

More information

Mons Memorial Museum (00 32 65 395 939; monsmemorialmuseum.mons.be)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments