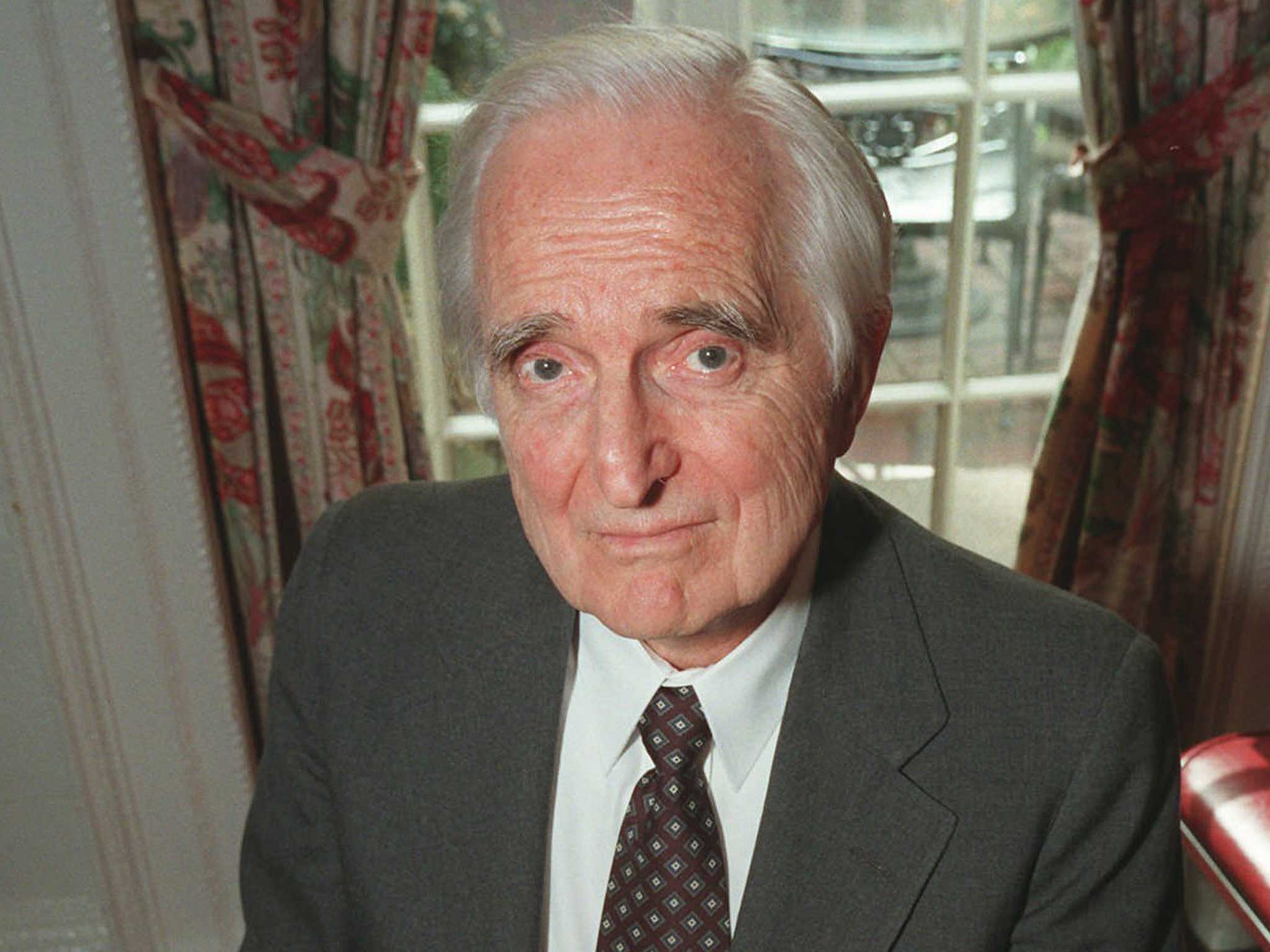

Doug Engelbart, the man who gave us a billion computer mice, dies aged 88

American inventor also behind hypertext, video conferencing, and shared desktops

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.For 50 years, Doug Engelbart watched the global mice population grow to more than a billion as Bill Gates and Steve Jobs double-clicked their way to fame and fortune with personal computers made possible by his first, wooden prototype.

Experts in computer interaction are now assessing the contribution of their founding father - who has died aged 88 - and the uncertain future of his greatest invention, the patent for which expired before it changed the world.

"There are a few moments in history where events change everything by changing the way we think about a problem," said Bill Buxton, Principal Researcher at Microsoft, which in 1995 deployed the mouse with Windows to revolutionise computing for the masses. "Engelbart's demo in '68 was one of those moments."

Jaws dropped that year at the Convention Center in San Francisco as Engelbart, wearing a stiff collar and tie, showed how his clunky box with "x" and "y" wheels could guide a pointer on a screen.

"Imagine the amazement that greeted the first iPhone and multiply it by five," said Mr Buxton.

For the first time, computer control had fallen into the hands of the layperson, even if the modern PC would take decades to arrive on desks and homes everywhere. "It took him 30 years to become an overnight success," said Mr Buxton, 64.

"The mouse opened up a whole new paradigm, transforming the way computers looked and the models we used to interact with them." said Russell Beale, professor of human-computer interaction at the University of Birmingham.

Lasers later replaced trackballs, killing off the mousepad industry at a stroke, but the modern mouse has faced a growing threat from touchpads and touchscreens.

Engelbart's own daughter Christina revealed last year that her children no longer used a mouse, and many predict its extinction. But not Mr Buxton. "For some tasks, the mouse will continue to be the most efficient and natural means of interacting with a computer," he said. "It will only be replaced for tasks where there is a better alternative."

Engelbart quietly continued his work after his invention, famous only among his peers. At the same 1968 demonstration in San Francisco, he had also hosted the first video teleconference and explained how text links would work, helping to lay the foundations for the internet.

Mr Buxton met him several times. "Even late in life, his enthusiasm and curiosity eclipsed that of many undergraduates I've known," he said.

Though Engelbart died in relatively modest circumstances, Mr Buxton, who also relinquished any rights to his work on touch screens, believes the inventor of the mouse was satisfied with his contribution to contemporary life: "When you see something you worked on 20 years ago all of a sudden go mainstream and have impact way beyond your dreams, that can't help but make you feel wonderful."

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments