From Lloyd's Legends to Ponting's Invincibles

The 10th World Cup begins this weekend, and it's changed enormously since the first tournament in 1975. David Lloyd charts the highs and lows of the game's biggest event

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

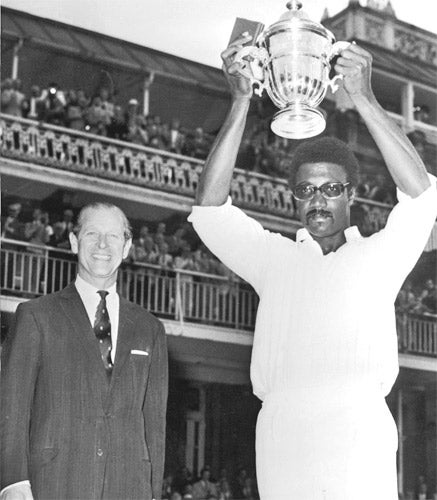

Your support makes all the difference.1975

Hosts England

Winners West Indies

modern day marketing executives would no doubt look back on the initial World Cup as a missed opportunity. Staged four years after the first official one-day international (between Australia and England), it was over in a fortnight, involved only eight teams, spanned a mere 15 matches, cost sponsors Prudential just £100,000 and yielded a modest £200,000 in overall takings (of which £4,000 went to the winners).

By way of comparison, this year's prize pot stands at more than £5m. What 1975 may have lacked in numbers, however, it made up with enjoyment and was widely acclaimed as an outstanding success.

The weather helped, supplying near wall-to-wall sunshine. An early match, between Australia and Pakistan at Headingley, saw the gates closed – something that had not happened at that ground for nine years – and most of the contests not involving guests East Africa and then minnows, Sri Lanka, were well attended.

It did not all go swimmingly, of course. Having watched England total 334 for 4 off the then ration of 60 overs (Dennis Amiss 137), an increasingly disenchanted Lord's crowd saw India make no attempt to reach their target. Opener Sunil Gavaskar was 36 not out when his team finished on 132 for 3.

The final, though, did the tournament proud. West Indies, everyone's favourites, made 291 on the back of Clive Lloyd's century but were made to fight hard by Australia for their 17-run victory. "The game has never produced better entertainment in one day," reported Wisden.

1979

Hosts England

Winners West Indies

Same venue, same format and same outcome. But at least this time the hosts, having lost a low scoring semi-final to Australia four years earlier, reached the Lord's showdown – where, like an all-ticket crowd of 25,000, they could only admire Clive Lloyd's unstoppable Caribbean machine.

England – with Mike Brearley as captain and including the likes of Ian Botham, Derek Randall and David Gower – had to work hard to reach their first final. Pakistan almost undid them at Headingley and then, in the semis, New Zealand failed by just 10 runs to reach a target of 222.

As for the final, well, that was just another Caribbean carnival. With Lord's jam-packed and many locked out, England did OK with the ball – until Viv Richards and Collis King decided to put on a show with a fifth-wicket stand of 139. Richards made a brilliant century, but it was King who dominated the partnership with an innings of 86 that included three sixes and 10 fours.

England were never likely to score the thick end of 300 in reply, especially with Geoff Boycott requiring 17 overs to reach double figures, and they eventually went down by 92 runs with Joel Garner and Colin Croft ripping through the middle and lower order. It was all good enough for the ICC to agree to make the World Cup a four-yearly event.

1983

Hosts England

Winners India

Having become a permanent fixture, the World Cup decided to get serious. Expansionism was the name of the game – and has been ever since.

There were still eight teams but, unlike the first two tournaments, they now played each other twice at the group stage. Instead of 15 games there were 27 and, as a result, gate receipts rose to well over £1m.

Perhaps the change the organisers most wanted, however, concerned the identity of the winners and in that regard they were brilliantly served by India, who started the competition as 66-1 outsiders yet beat West Indies twice along the way – in their group and then in the final.

As for England (with a middle order of Gower, Lamb, Gatting and Botham and an attack led by Willis, Dilley and Botham), they made almost serene progress to the semi-finals. There, though, the wheels came off, India beating them by six wickets on a slow Old Trafford pitch.

Surely the final would go the way of the previous two? Not so. India were dismissed for an apparently unthreatening 183 but their medium-pacers strangled the life out of the West Indies batsmen (Greenidge, Haynes, Richards and Lloyd to name but four) to set up a remarkable 43-run victory.

1987

Hosts India & Pakistan

Winners Australia

India joined forces with Pakistan (a significant triumph in itself) to stage the tournament's fourth edition. And, despite plenty of initial scepticism, this one turned out to be the best yet in terms of spectator numbers and closely fought cricket.

The biggest drawback was the scale of the operation. There was always going to be plenty of travel but by picking 21 venues in the two countries the joint management committee saddled most teams with at least one nightmarish journey.

Still, most of the games were worth the effort in getting there. And, having failed to win a World Cup in their country, England really should have lifted the trophy after stunning India with a brilliant semi-final victory in Bombay.

Gooch, having decided to sweep the home spinners at every opportunity, scored a terrific century before Eddie Hemmings' slow bowling earned four wickets in 34 balls to set up a 35-run win.

Now only Australia stood between Mike Gatting's team and a major triumph. 70,000 spectators saw the match turn decisively in Australia's favour when Gatting unwisely aimed a reverse sweep at Allan Border's first ball to be caught behind. Australia were clearly on the rise after a miserable few years.

1992

Hosts Australia & New Zealand

Winners Pakistan

All change, again. Well almost. Despite reaching the final for a third time, England once more failed to capture the main prize – beaten on this occasion by Imran Khan and his "cornered tigers".

Fifteen matches in 1975 and 1979 became 27 in 1983 and 1987. Now the number of contests increased to 39, and there were nine teams rather than eight. The reason? South Africa had just returned following their long spell of isolation. Add the introduction of coloured clothing and the fact some games were played under floodlights and this event had a whole new feel.

A new method for calculating targets after rain interruptions was controversial. In a semi-final against England, South Africa needed 22 off 13 balls when the weather intervened. On returning to the middle they were told they required 21 runs... from one ball.

Whereas Pakistan grew in strength, England probably peaked too soon. Even so, they had Pakistan in trouble during the early stages of the Melbourne final and still had a decent chance of success when set 250. Mushtaq Ahmed's spin and Wasim Akram's swing did for them, however – leaving beaten captain Graham Gooch to declare: "It's not the end of the world. But it's close to it."

1996

Hosts India, Pakistan & Sri Lanka

Winners Sri Lanka

The sixth World Cup went back to the sub-continent and, for the first time in the competition's history, it provided a home winner (although the final was in Pakistan and Sri Lanka were very much junior hosting partners). But unlike 1987, this was an event with more cons than pros.

Problems began before the tournament started with Australia and West Indies refusing to play in Colombo following a bomb blast. Both sides forfeited the points, not that it mattered so far as qualification was concerned. The idea of inviting 12 teams was sound but the decision to put them in two groups of six from which the top four would advance had no merit at all. Other than making money.

As a result, England were able to reach the quarter-finals through beating the Netherlands and the UAE. A lot of good it did them, mind you, with Sri Lanka lying in wait.

Whereas England's cricket looked horribly behind the times, Sri Lanka blazed a revolutionary trail – mainly thanks to the thrill-a-ball batting of openers Sanath Jayasuriya and Romesh Kaluwitharana. And when those two failed, Aravinda de Silva and Arjuna Ranatunga took charge.

Most people loved Sri Lanka's approach, but enough Indian supporters began throwing bottles in dismay at their side's looming defeat in Calcutta for the semi-final to be abandoned. Sri Lanka marched on, then brushed aside Australia to lift the trophy.

2003

Hosts South Africa, Zimbabwe & Kenya

Winners Australia

Now captained by Ricky Ponting, Australia did not just hang on to the trophy – they refused to let anyone get within touching distance. Played 11, won 11, and that despite the shock of having to send Shane Warne home following a failed drugs test.

The superiority of the Australians should have been the only real talking point. But it wasn't, of course, because the decision to give Zimbabwe and Kenya a share of the hosting rights meant that politics and security issues took centre stage.

New Zealand refused to play in Nairobi, where there had been recent terrorist atrocities. As for England, they became embroiled in a deeply damaging saga over whether it was right to play in Zimbabwe. They did not travel; points were forfeited.

In the end, it was left to two Zimbabwe players, Andy Flower and Henry Olonga, to make the one statement that carried real weight. Both wore black armbands during their game against Namibia "mourning the death of democracy" in a country brutally ruled by Robert Mugabe.

The two best teams reached the final – and the best of the lot won by a distance. Australia, led by Ricky Ponting's brilliant unbeaten century, cruised to a 125-run victory over India.

2007

Hosts West Indies

Winners Australia

It was fitting, perhaps, that the final should end in farce with match officials forcing Australia and Sri Lanka back on to the field in near darkness when everyone else inside Kensington Oval, Barbados, knew that, under the rules of the competition, the holders had already retained their trophy.

In fairness, the two sides deserved better – especially Australia, who again won 11 out of 11 and were even more commanding than they had been four years earlier. But so much of the tournament was a mess that few could feel sorry for the organisers when the final went wrong.

A World Cup in the Caribbean should have been a carnival of cricket. Instead, too many of the people who could have made it a magical affair were kept away by the high cost of tickets. And those who did manage to find the necessary dollars were prevented from doing things like drinking their own rum and blowing their conch shells.

Several events beyond the control of the organisers cast an even darker shadow. By far the worst was the death of Pakistan's coach, Bob Woolmer, in his hotel room. The former England batsman succumbed to natural causes but Jamaican police initially announced he had been strangled.

Only Sri Lanka seemed to be on the same planet as Australia but they bent the knee once Adam Gilchrist graced the final with a terrific century.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments