Astronomers discover most eccentric young star system

Looking for fossils of planet formation, scientists were surprised at the strange and complex shape of a nearby star system

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Astronomers have discovered the most eccentric, off-kilter belt of comets surrounding a nearby star to date, a surprising observation for scientists looking for a stellar sibling to our own Solar system.

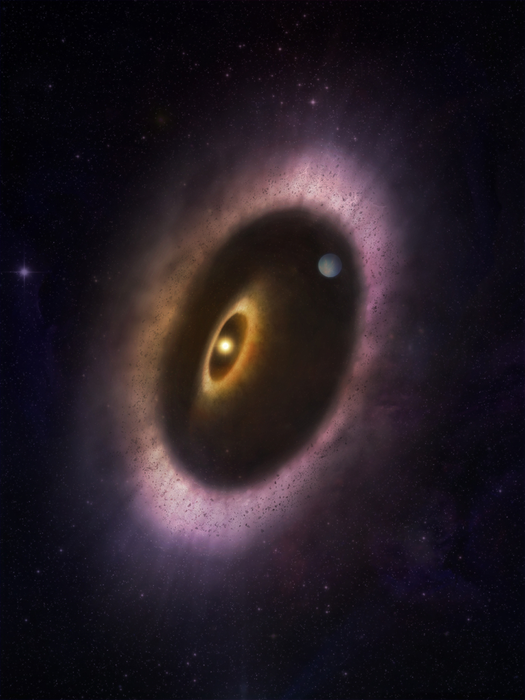

In a presentation at the 240th meeting of the American Astronomical Society in Pasadena, California on Tuesday, researchers described new radio telescope observations of the star HD 53143. A relatively young star at about a billion years old, and located around 60 light years away in the Carina constellation, HD 53143 turned out to be surrounded by a much more complicated and eccentric — meaning elliptical rather than circular — disk of comets than earlier Hubble Space Telescope observations suggested.

“Until now, scientists had never seen a debris disk with such a complicated structure. In addition to being an ellipse with a star at one focus, it also likely has a second inner disk that is misaligned or tilted relative to the outer disk,” assistant professor of astrophysics and astronomy at Colorado University, Boulder and lead author of the study Meredith MacGregor said in a statement. “In order to produce this structure, there must be a planet or planets in the system that are gravitationally perturbing the material in the disk.”

Astrophysical Journal Letters will also publish the findings in an upcoming edition.

The Hubble first observed HD 53143 in 2006 using a coronagraph, a device that blocks out a star in an observation to allow better viewing of whatever orbits the star. The coronagraph allowed Hubble to note the debris disk around the star — a ring of comets and dust at the star system’s periphery — but not the location of HD 53143 relative to the disk.

Rather than using visible light, or even infrared astronomy, the new paper observed HD 53143 using the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array, or ALMA, in Northern Chile, making the first millimeter radio wavelength observations of the star system. What Dr MacGregor and her colleagues found was that rather than a fairly circular ring of comets with HD 53143 at the center, the ring was highly eccentric, with the star located at one end of the ellipse. It's a finding that suggests exoplanets could be influencing the shape of the debris disk around the star.

“In general, we don’t expect disks to be very eccentric unless something, like a planet, is sculpting them and forcing them to be eccentric,” Dr MacGregor said in a statement. “Without that force, orbits tend to circularize, like what we see in our own Solar System.”

Our Solar System has its own planets however, and so planets alone are not sufficient to generate an eccentric debris disk. Our Solar system’s debris disk is the Kuiper belt, the ring of comets and planetesimals beyond the orbit of Neptune, and which Nasa’s New Horizons mission has been exploring since its 2015 flyby of Pluto.

The Kuiper belt and the debris disks of other star systems are of interest to scientists because they are remnants, time capsules of the early days of solar systems and can help scientists better understand how planets, including Earth, form and evolve over time.

“We can’t study the formation of Earth and the Solar System directly, but we can study other systems that appear similar to but younger than our own,” Dr MacaGregor said in a statement. “Debris disks are the fossil record of planet formation, and this new result is confirmation that there is much more to be learned from these systems and that knowledge may provide a glimpse into the complicated dynamics of young star systems similar to our own Solar System.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments