What can US trigger-happy cops learn from Britain's gunless police?

American police kill the same number of people with guns in a day that UK officers do in a year. Griff Witte, an American Washington Post reporter working in London, reports

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.To join the few and the proud who police Britain’s streets with a gun, first you have to walk the beat unarmed for years.

Then there is the rigorous selection process — an unforgiving complement of fitness tests, psychological appraisals and marksmanship exams. Finally, there is the training, which involves endless drilling on even the most routine scenarios.

“They rehearse those situations like a SEAL team trying to get into Osama bin Laden’s compound,” Cambridge University criminologist Lawrence Sherman said.

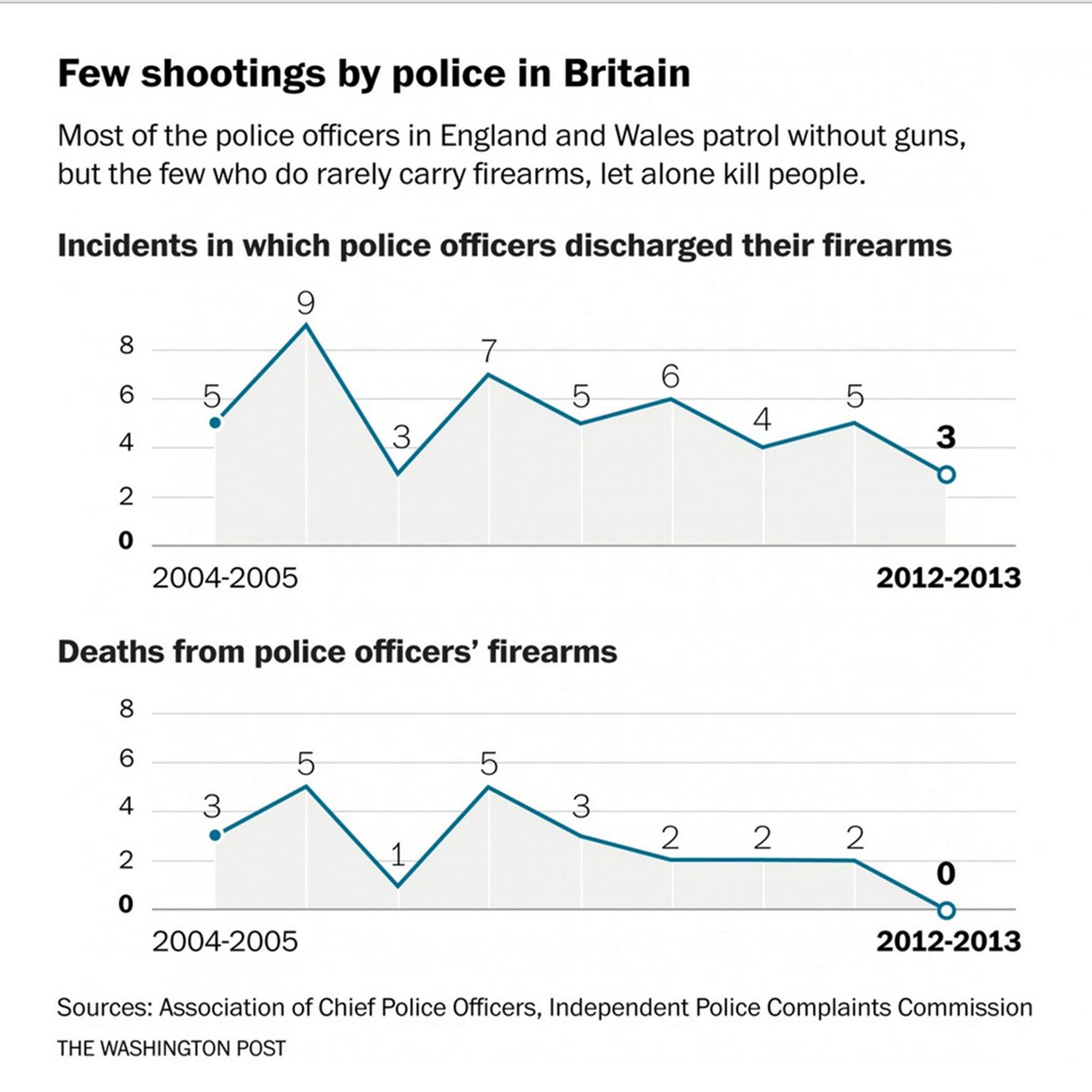

Yet, in a country where the vast majority of police officers patrol with batons and pepper spray, the elite cadre of British cops who are entrusted with guns almost never use them. Police in Britain have fatally shot two people in the past three years.

That’s less than the average number of people shot and killed by police every day in the United States over the first five months of 2015, according to a Washington Post analysis.

As the United States reckons with that toll — and with the constant drip of videos showing the questionable use of force by officers — lightly armed Britain might seem an unorthodox place to look for solutions. But experts say the way British bobbies are trained, commanded and vigorously scrutinized may offer US police forces a useful blueprint for bringing down the rate of deadly violence and defusing some of the burning tension felt in cities from coast to coast.

Of course, British and US police are patrolling different societies. The United States has some of the world’s loosest gun laws and some of the highest rates of gun ownership.

Britain is the opposite, with handguns and assault rifles effectively banned.

That inherently changes the way police officers do their jobs.

Phil Palmer was a British police officer for 15 years and was stabbed twice in the line of duty.

“But in all my time, I never expected to have to deal with anyone with a firearm,” he said.

During a year in the United States teaching and working with New York City police officers, he quickly realised that they had a very different expectation.

“They were very professional. But every time they got out of their car to talk to someone, their hand would hover over the gun,” said Palmer, now the co-director of the Institute of Criminal Justice Research at Britain’s University of Southampton. “Police in America are more aggressive, and I think that’s because they have to be.”

But there are also enough similarities that the British model carries special relevance. Like the United States, Britain is large, urbanized, democratic and diverse. Police have to reckon with gang violence, organized crime and Islamist extremists, all amid persistent allegations that they unfairly target minority communities.

That puts Britain in a different class than the handful of other nations that largely forgo firearms when policing, including New Zealand, Iceland, Ireland and Norway.

Few here would argue that the United States should adopt Britain’s nearly firearms-free approach. But as increasingly horrified British officers and commanders have watched videos of American police officers firing on civilians, they say they hope that some of their strategies and practices can be translated across the Atlantic.

Sir Peter Fahy, chief of the Greater Manchester Police, commands 6,700 officers — just 209 of whom are armed. Those authorized to carry guns, he said, face extremely tight protocols governing when they can be deployed and under what circumstances they can fire. Shooting at moving vehicles, at people brandishing knives and at suspects fleeing a scene are all strictly forbidden except under extreme circumstances.

“It’s very controlled,” he said. “There’s a huge emphasis on human rights, a huge emphasis on proportionality, a huge emphasis on considering every other option.”

All officers, he said, are taught to back away from any situation that might otherwise escalate and to not feel that they have to “win” every confrontation.

“I constantly remind our officers that their best weapon is their mouth,” he said. “Your first consideration is, ‘Can you talk this through? Can you buy yourself time?’ ”

That mantra helps explain why, across England and Wales over the past decade, there has been an average of only five incidents a year in which police have opened fire.

So, too, does the stringent screening process. Officers must serve for years before they can apply to carry a gun, and the selection of those deemed worthy is intensely competitive.

When Mark Williams applied to be a firearms officer in 1995, he was among a group of 16 who started the grueling regimen of physical and psychological trials. Three made it.

Williams was among them, but that wasn’t the end of the testing. He and his fellow firearms officers faced regular drills challenging them to find creative ways out of confrontations and spent long nights at the shooting range to upgrade their marksmanship.

“If you fired the kind of rounds we did, you’d be bankrupt,” said Williams, who is now chief executive of the Police Firearms Officers Association. “We can put a lot of effort into the ones who are armed, because there aren’t that many.”

Some aspects of British policing are more easily transferrable. Sherman, the Cambridge criminologist, recently told a White House task force that the United States should create a national college of policing, that states should set up police inspectors general to provide oversight and that local police forces should merge to achieve a minimum standard of 100 officers per department. All are steps, he said, that have worked in Britain.

Of course, police shootings here can still arouse intense debate. One of the most prominent came in 2005, when a Brazilian electrician, Jean Charles de Menezes, was mistakenly identified as a would-be suicide bomber and shot nine times in the head by elite officers in a Tube station in London.

Prosecutors chose not to charge anyone with his killing, a decision his family is challenging this week at the European Court of Human Rights.

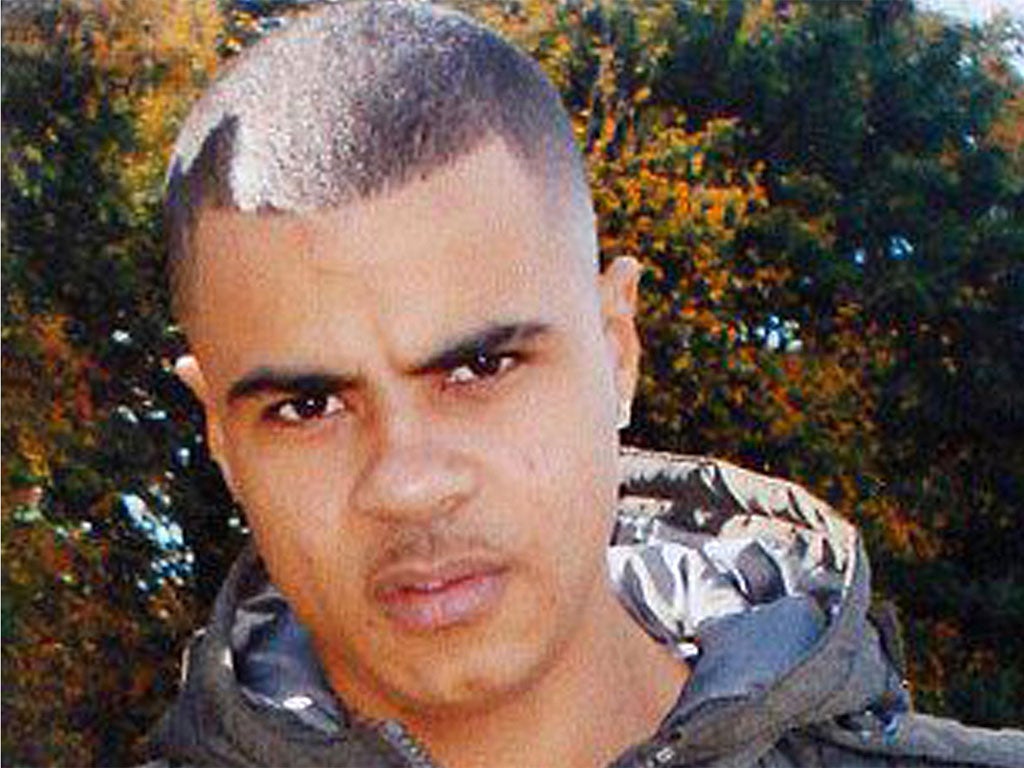

In 2011, police shot dead a 29-year-old black man, Mark Duggan, prompting several nights of riots across London. An inquest later ruled the killing had been lawful because police had ample reason to believe that Duggan was armed. But rights groups say the killing, and others like it, raise questions about police practices that echo concerns in the United States.

“They may well be fewer here, but they raise similar issues,” said Deborah Coles, co-director of Inquest, an advocacy group.

Still, there is little doubt that Britain has a more uniform and transparent process for reviewing such cases.

Every police killing here is subject to an independent inquiry, and even nonfatal shootings are meticulously tracked and evaluated.

Sir Denis O’Connor, a former police chief who later served as a royally appointed independent overseer of British police work, said cops here take seriously the idea of “policing by consent.” They see themselves as working for the public, he said, rather than for the state itself.

They also know that someone is always looking over their shoulder.

“The cops here tend to fear getting it wrong and being criticized by a judge,” he said. “Cops in the U.S. fear getting shot. Those are two very different worlds.”

Copyright: Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments