How to win the election: Political speeches are no longer delivered but 'framed' to ensure you hear the core message

Platitudes apart, don’t expect politicians to talk plainly in the run-up to the election. Diplomat-turned-communications expert Charles Crawford reveals why they prefer 'framing' their rivals (and exposes the Dead Cat Denial)

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Looking over various lists of Great British Speeches, you spot something interesting. Almost none has been delivered during an election campaign.

One that sometimes makes the cut is Neil Kinnock's "I Warn You" speech two days before the 1983 General Election, when it was clear that Labour was going to lose big.

Labour supporters gush that this unambiguously attention-catching oration was one of the finest ever made in British politics: "If Margaret Thatcher is re-elected as Prime Minister on Thursday, I warn you. I warn you that you will have pain – when healing and relief depend upon payment. I warn you that you will have poverty – when pensions slip and benefits are whittled away by a government that won't pay in an economy that can't pay... I warn you not to be ordinary. I warn you not to be young. I warn you not to fall ill. I warn you not to get old."

Well, this scores strongly on thudding rhetoric. But it scores even more strongly on nonsense. British voters have a keen ear for noisy cant. They know that Labour, Conservative and now coalition governments alike do not – and cannot – bring in apocalyptic changes. For the most part they boss us around and tweak things. Frantic Kinnockite warnings that the End is Nigh make no sense, so anyone proclaiming that comes across as losing the plot (and indeed the election).

Another reason why election speeches are rarely memorable is that they have to do several largely incompatible jobs simultaneously and end up being a mish-mash. Galvanise supporters by emphasising the speaker's positives. Demolish opponents by pouncing on gaffes and emphasising the opponents' negatives. Woo the undecided by sounding reasonable, competent and principled. Convey information. And create just the right tone. The tone must work for the occasion and its immediate audience on the day and complement the wider campaign policy themes. Tone is the hardest to get right, but has real power when it works.

A core part of getting the right tone for political campaigns is a technique known in psychology jargon as "framing". People listen to the logic of speeches, but they also respond subliminally to the way issues are presented. The motif of top US speechwriter Frank Luntz's mighty book on public speaking, Words That Work, is spot on: "It's not what you say – it's what people hear." What basic word or words does a speaker want voters to "hear" from a speech and from the campaign as a whole? US far-left activist Saul Alinsky featured this idea in his infamous Rules for Radicals: "Pick the target, freeze it, personalise it, polarise it."

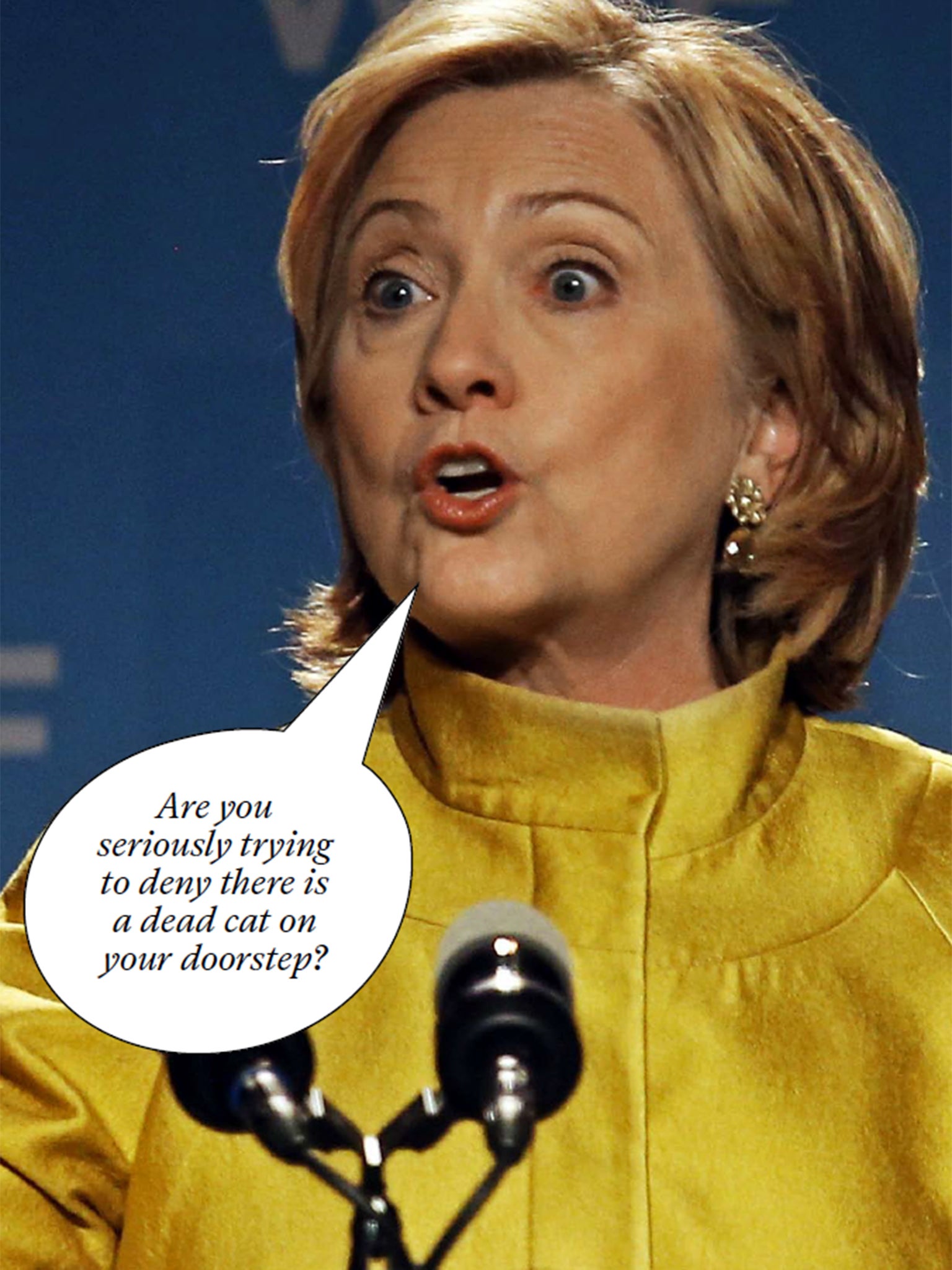

A classic framing ploy is the Dead Cat Denial. You untruthfully accuse your opponent of having a dead cat on the front doorstep (or some other seemingly unpleasant fact). When your opponent exclaims crossly that this is utterly untrue, you slyly reply: "Ah, now you're denying that you have a dead cat on your doorstep?"

The ensuing angry denials from your opponent create a general mood that this person is always banging on about dead cats. After all, if there isn't a dead cat or other dead animal there at the house somewhere, why is he or she getting so emotional about it? Perhaps too emotional in general to be trusted? You tip-toe away, seed of doubt sown. Mission accomplished: a sneaky reputational frame-up.

In his 2008 election campaign Barack Obama took framing to a giddy new height. He led on "Hope and Change". He not only sold that bland but positive slogan as a dynamic policy mandate. He sold himself as epitomising hope and change. If John McCain had an election slogan at all, it sank without trace. Worse, by virtue of his misfortune in not being Barack Obama, McCain was open to attack as opposing hope and change themselves, and what can be more odious than that? Watch what happens if Hillary Clinton gets the Democratic nomination next time. Any mere male who dares disagree with her ipso facto will be "framed" as a sexist reactionary.

In UK parliamentary politics it is difficult (and unwise) to make an election all about any leader's personality, even if this time Ed Miliband presents a vivid target. There are instead two main rhetorical framing themes: "It's time for a change!" and "Steady as she goes!" They touch something deep in each of us, namely our attitude to risk. Parties currently in opposition of course press the case for change. The party or parties in government emphasise continuity, unfinished business, keeping a straight course. The Scottish independence referendum turned on exactly this change-versus-continuity contrast. So will any eventual EU exit referendum in the UK.

To deliver these themes the political parties have two main options: crush their opponents' arguments by facts and/or logic; or steal their rivals' best trousers and wear them as their own. Tony Blair won successive elections for so-called "New" Labour precisely by espousing a number of core Conservative policies: "You like tough leadership and more privatisation, but you want them delivered by people who care!" This time round, the Conservatives are distancing themselves from any threadbare Labour trousers, hammering at the apparent inconsistency of Labour's economic policies: "Those Brownites made us sick – now they're moaning about our medicine, even though everything is far healthier today!"

When you know what our parties are up to with these annoying framing tricks in speeches and their Today programme soundbites, you hear nothing else. Tories led by David Cameron are "posh" and don't "care"! Lib-Dems are sell-outs! Labour are "wreckers" or "stupid", led by the "weird" Ed Miliband. Ukip are "racists", "nutters", "xenophobes". In Scotland, both Labour and the Conservatives opposed independence so, according to the SNP, they're "against Scotland". They in turn frame the SNP as "dishonest".

The election and its speeches thus become a battle of competing framings. Labour is now having some success in framing the key election issue as the NHS: despite the horrors of Mid-Staffordshire and other NHS disasters on the long Labour watch, they are presenting themselves as uniquely "caring" (and "not posh"). Are the Conservatives victims of their own success on the economic policy front? Maybe there are now enough feel-good economy numbers to persuade voters they can afford to give other issues priority.

Back in real life, no UK political party knows what to do about the fact that a sprawling, administration-heavy NHS is doomed to decline as new technology opens up completely different ways of linking people to medical procedures and healthy living. Instead of offering voters a frank explanation of the issues, they retreat into empty slogans and senseless, cherry-picked statistics.

This next election is unusually complicated, as the row over TV debates shows. Our voting system wisely makes it hard for smaller parties to make meaningful breakthroughs, but voters here, as elsewhere in Europe, are clearly restless with the status quo. This means Conservative and Labour alike have to fight a rhetorical war on several fronts, firing heavy shots at each other while keeping enough ammunition in reserve to snipe efficiently at the pesky Ukippers, Greens, SNP and hapless Lib-Dems.

Ukip and the Greens by contrast have a free hand. They have not been in power so can't be blamed for anything. And because they are unlikely to win many seats even if they get great lumps of votes, they can be as belligerent, funny, populist and even irresponsible as they like. In Scotland, Labour may be washed away by the SNP in the ripples of the independence referendum, a blow to its nationwide majority hopes. The Lib-Dems are in the grim position of being squeezed from all sides, but not having a coherent thematic response.

A messy situation. So, in their speeches, the Conservatives will frame the basic choice in their "target voter space" in the simplest terms: "Every vote for Ukip is a vote for that nutty wrecker Ed Miliband! If you want lots more EU, that's the way to get it!" Labour has a trickier task (as anything it says on the economy will be dismissed with derision): "Every vote for the Greens/Ukip/SNP is a vote for posh uncaring Cameron: we are the only credible competent national option who loves the NHS!" It will suit both parties to ignore the Lib-Dems, framing them as irrelevant if not already deceased.

That said, all good election speeches have a strong local feel. I recently watched David Cameron at a rural Conservative gathering, confidently swiping at Labour and defending the Conservative record. But the biggest cheer came when he mentioned government plans to improve a busy constituency road. That shows one basic public speaking principle that politicians forget at their peril: any every speech should respect where the audiences are in their lives. So party manifestoes and election speeches will not say much about Europe, the Ukraine, Islamic jihad, global trade talks and other pressing international themes. Too foreign. Too complicated. Voters hear "boring".

Something specific to look out for in election speeches? Our leaders want to show themselves driving forward significant improvements, but they want to avoid blame when things go wrong or promised policies aren't implemented.

How, then, to draft speeches that convey leadership and purpose, while avoiding responsibility for failure? We find the answer in the musty, needy speeches.

I first noticed this phenomenon in Foreign Secretary David Miliband's speech in Warsaw in 2009. It was stuffed with these phrases. He said that we "needed": a compelling positive case for the European Union; bold strokes; to deepen cooperation and incentivise reform; more solidarity between member states; to prepare better for energy shortfalls; and to make G3 cooperation work.

The EU "must" (he also said) adapt once again to the changing geopolitical context we face; set itself a goal of creating a single, low-carbon energy market; and speak with a strong voice to engage the main global powers.

This is high-order junk speechwriting and faux leadership, based on depersonalised verb forms. It is all about what everyone other than the speaker "must" or "need" do. And once you start listening for musty, needy exhortations, you find them all over the place.

Take the number of "must"s in President Obama's feeble TV speech about Israel and the Middle East from March 2013: "Assad must go so that Syria's future can begin. Iran must not get a nuclear weapon. America will do what we must to prevent a nuclear-armed Iran. The Palestinian people's right to self-determination must also be recognised; and Arab states must adapt to a world that has changed."

The fusillade of musty requirements hints at some visionary purpose while side-stepping personal or political responsibility for what actually happens.

However, while we voters might despise our elected leaders' slippery language, how might we respond if they started being honest, telling us that the sheer complexity of modern life is reducing towards zero their capacity to achieve good new outcomes? Answers come there none.

My own favourite election speech? One in a long-lost David Austin "Hom Sap" cartoon in Private Eye. As I recall it, the Roman leader berates the crowd who respond accordingly:

"The masses are stupid!"

"Boo!"

"The masses are lazy!"

"Boo!"

"The masses can be bribed!"

"Ah, now you're talking…"

Charles Crawford's new ebook 'Speechwriting for Leaders' is available on Amazon

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments