General Election 2015 explained: Broadcasting

Our daily miscellany of electoral facts, figures and folklore continues with a selection of essential and not-so-essential information about who rules the airwaves during a British general election campaign

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.No.2 Broadcasting

Election night coverage

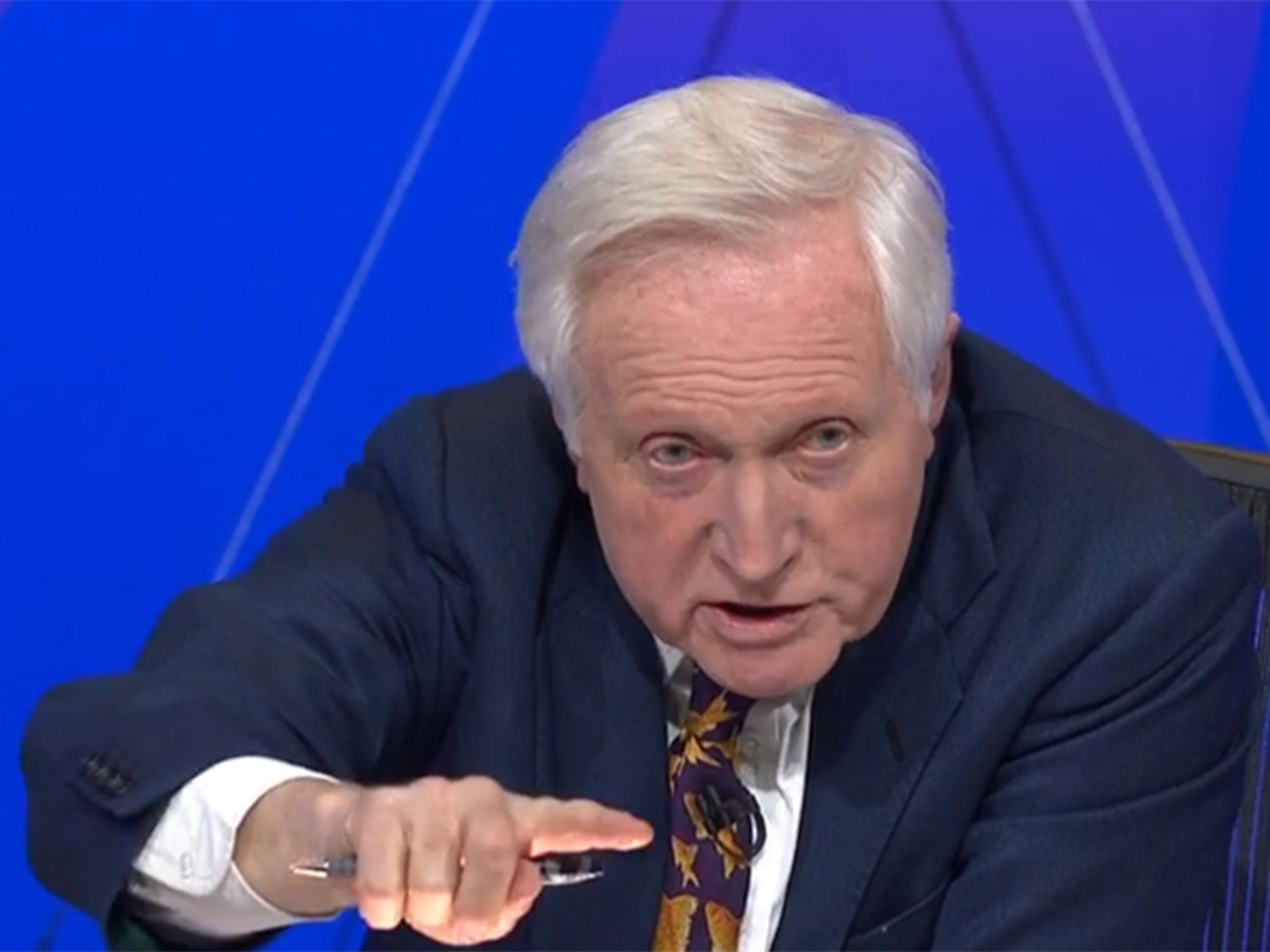

On the night of 7 May, David Dimbleby (supported by Nick Robinson, Jeremy Vine, Emily Maitlis and Andrew Neil) will anchor the BBC’s coverage of his ninth and last general election, from 10pm-7am. Huw Edwards will then take over, continuing to host coverage until 10pm.

Sky News is adopting a less studio-based approach, with Kay Burley, Jeremy Thompson and Anna Botting leading its coverage from locations around the UK.

Tom Bradby will lead ITV’s coverage, from 10pm to 6am, supported by Julie Etchingham in a “bespoke virtual studio” Channel 4’s coverage will be anchored by Jeremy Paxman.

It is possible, however, that the unprecedented volume of election night coverage available online and on social media – as well as radio – will result in fewer people considering it essential to spend election night glued to a television screen.

A brief history

The first election-night television broadcast in the UK was the BBC’s 1950 Election Results (including a black, white and grey electoral map). The first televised Party Election Broadcasts went out in 1951.

In 1955, Richard Dimbleby hosted a more ambitious Election Results programme. Constituencies rushed to get their results out, and 357 (out of 630) declared on the night. But concerns about the Representation of the People Act (1948) meant coverage was sober, with little commentary.

The arrival of ITN (launched in 1955) and the spread of television ownership spurred the BBC into a more user-friend ly app roach for the 1959 election. Around 13 million vie wers watched the BBC’s election night coverage that year.

Between 10pm on 7 May and 1am on 8 May 2010, an average of 8.202 million vie wers were watching election programming across BBC1, ITV1, Channel 4, Sky News, BBC News Channel, BBC HD and ITV1 HD. BBC1 took 30.7 pe r cent of that audience. Between 10.45pm and 11pm, its audience hit a peak of 5.759 million.

Broadcasting rules

Under electoral legislation, television and radio broadcasters have to follow a code of practice in their coverage of candidates during election periods. Ofcom is responsible for the code regulating independent broadcasters; the BBC and S4C have to draw up (and observe) their own. In both cases, the guiding principles are that, in the words of the Electoral Commission, broadcasters should “achieve an appropriate balance… Broadcasters are not required to give exactly the same amount of coverage to each candidate, but are required to have regard to the relative electoral strength of the candidates and their parties.”

The BBC’s guidelines add that, during a campaign, particular programmes or programme strands are expected to achieve balance over “an appropriate period, normally a week” rather than in every single bulletin.

BBC guidelines also forbid the commissioning of opinion polls during the election period and restrict other forms of quantifying support for parties, such as online surveys and text votes or reporting polls that others have commissioned. A range of other activities, from seeking interviews with party leaders to covering political subjects on programmes that do not usually deal with such matters, are permissible only with specific clearance by the Chief Adviser, Politics, Ric Bailey.

TV debates

The first televised UK general election debates between party leaders took place in 2010, 50 years after US presidential candidates first took part in such an exercise. The three th ree -way confront ati ons were broadcast on successive Thursdays on ITV, BSkyB and the BBC and resulted in a surge of support for the Liberal Democrats.

The nearest thing to an all-party leade rs’ confrontation that we will see in the current campaign was the seven -way deb ate on ITV on 2 April. This drew an average audience of seven million vie wers – a 31 per cent share of the total audience.

The BBC will show a five-way deb ate between opp ositi on party leaders this Thursday (16 April), and David Cameron, Ed Miliband and Nick Clegg will be guests on the BBC’s Question Time (presented by David Dimbleby) on 30 April.

The Battle for Number 10, Jeremy Paxman’s interrogation of David Cameron and Ed Miliband on Thursday 26 March, was watched by 2.6 million people on Channel 4 and 322,000 on Sky News; a further 255,000 saw its simulcast on the BBC News channel.

Debates (and not-quite-debates) take place on Thursdays to avoid clashes with Champions League football. Sadly, in 2015 as in 2010, the last British clubs exited the competition long before the election campaign began.

Party election broadcasts

Party election broadcasts (PEBs) should be distinguished from party political broadcasts (PPBs). The former appear only during election campaigns.

The first PEBs were delivered on radio by the leaders of the three main parties during the 1924 gene ral electi on; the first non-election PPBs, also on radio, were given in 1926.

The first televised PEB, in 1951, was a shambolic affaIR. Lord Samuel, the 81-year-old leader of the Liberals in the Lords, delivered what was supposed to be a 15-minute address but turned out rather longer. He read it without looking up from his script, and was cut off in mid-sentence after inadvertently giving a pre-arranged signal to indicate that he had finished.

Under Section 333 of the Communications Act 2003, Ofcom must ensure that licensed public television services and national radio services include PEBs for registered parties on the following basis: “major parties” should be offered a series of “two or more” PEBs. Other registered parties qualify for a PEB in a general election if they are contesting one-sixth or more of the seats.

Parties which qualify for a PEB in England, Scotland and Wales also get slots on Channel 4 and on Five. The BBC and S4C are also required to carry PEBs but are not regulated by Ofcom. Sky carries PEBs as well, but is not obliged to do so.

“Major parties” has traditionally been taken to mean Conservative, Labour, Liberal Democrats; and, in their respective regions, SNP, Plaid Cymru, the Democratic Unionist Party, Sinn Fein, the SDLP and the Ulster Unionist Party. In March, however, Ofcom announced that Ukip had been added to the big three.

PEBs on television on behalf of the “major parties” must be broadcast bet ween 6pm and 10.30pm. Parties must choose between three possible lengths of broadcast:

2 minutes 40 seconds

3 minutes 40 seconds

4 minutes 40 seconds

According to Ipsos-MORI, 70 per cent of the electorate saw at least one party election broadcast during the 2010 campaign.

The Dimbleby Factor

Heredity plays no formal part in election broadcasting. However, it may sometimes appear to do so. The late Richard Dimbleby anchored the BBC’s election night coverage in 1950, 1955 and 1959.

His son David Dimbleby took on a similar role in 1979 – and has continued to perform it for every general election since, as well as chairing one of the televised leaders’ debates for 2010. In addition, since 1997, David’s brother Jonathan Dimbleby has anchored election night coverage for ITN.

David Dimbleby (who in 2013 acquired a scorpion tattoo on his shoulder) also traditionally commentates on the State Opening of Parliament.

The swingometer

Created by Peter Milne in 1955, and subsequently refined by Bob McKenzie, the Swingometer was a device (originally cardboard) used by broadcasters to show graphically the impact of different de gree s of swing on party representation in Parliament.

From 1992 to 2005 it was enthusiastically operated by Peter Snow and became a familiar feature of the BBC’s election coverage.

Its success prompted ITV to try various rival devices, such as the KDF9 in 1964 and the VTF30 (based on a knitting-pattern machine) in 1974; but they never captured the nation’s imagination in the same way.

Snow’s retirement, the rise of computer graphics and the decline of two-party politics have all contributed to a decline in the Swingometer’s significance. On election night, Jeremy Vine will use a four-sided digital version, modelled on Big Ben, in an attempt to reflect the new realities.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments