Jack Reece: Police officer who caught Patrick Magee, the man who bombed the Grand Hotel in Brighton

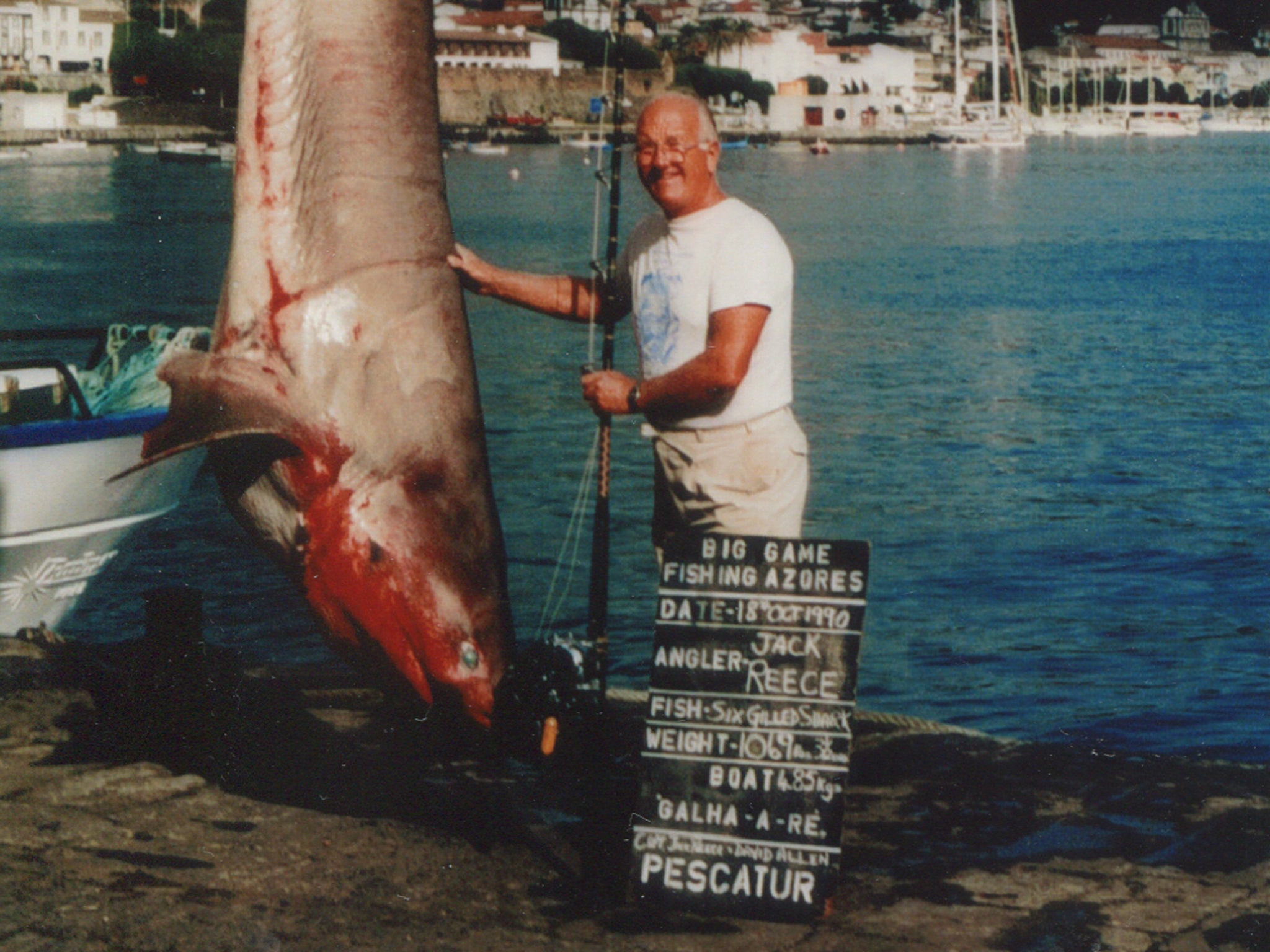

A keen fisherman, Reece’s biggest catch in the non-policing world was a six-gilled shark

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The seasoned eye of Detective Chief Superintendent Jack Reece scanned the Brighton seafront. As a sea fisherman, he knew the tides. Those potted shrubs along the beach might contain vital evidence. “Get these tubs in before the waves reach them,” he ordered. “Anything there would be irrevocably lost.”

In fact the evidence that Reece, head of Sussex CID, wanted lay on a hotel booking card. It was to take him 20 months to get his man – the man who had tried to assassinate the Prime Minister, Margaret Thatcher, taking five lives and injuring 31 in the attempt.

Behind Reece on that fateful Friday morning of 12 October 1984 towered the pale, ornate façade of the Grand Hotel, split by an ugly black gash where a bomb had gone off in the middle of the night. “It appeared as if a huge gaping lift shaft had opened up with all the debris and evidence sinking to the bottom,” Reece recalled.Many ministers had been inside, attending the Conservative Party conference. “I’ll never forget finding the bodies, and talking to the relatives. I don’t know how they cope after something like this,” he reflected years later.

For the burly 6ft Yorkshireman known as “big Jack”, the £1m investigation, which put him on an IRA death list, was to test his leadership, keeping up staff morale in the long hunt – and, at its end, his steadiness under questioning in court. Reece identified the IRA bomber, Patrick Magee, from fingerprints on the booking card of “Roy Walsh”, the name he had used when he stayed at the Grand Hotel from 15-18 September. Magee had planted the bomb, with a long-term timer, wrapped in plastic to deceive sniffer dogs, under a bath in Room 629.

Reece travelled to Glasgow for Magee’s arrest in a flat there in June 1985, after Magee, thinking himself unsuspected of the Brighton murders, returned to the mainland to plan further attacks. Magee’s defence team at the Central Criminal Court drew from Reece an exclamation – “Preposterous!” – when in cross-examination before Mr Justice Boreham in 1986 defence counsel said: “I put it to you that you planted these fingerprints and palm prints.” Magee and four others were found guilty and jailed.

There would be a further shock for Reece when Magee was released under the Good Friday Agreement of April 1998. “We worked our butts off to get that result”, Reece observed. “Here he is out in 14 years... I think it makes a laughing stock of justice.” When Magee returned to Brighton in 2004 to meet a victim’s relative and take part in a discussion, Reece remained sceptical of his motives, remarking: “What on earth is he going to pontificate about in Brighton, when he hasn’t repented?”

Reece had earlier led inquiries that in 1975 caught the attempted kidnapper of a viscountess, Lady Devonport, briefly seized from her bedroom before a police car arrived, causing the miscreant to flee. And he had taken part in Operation Countryman, which between 1978-82 shed light on alleged corrupt police practices in London, though prosecutions failed.

Reece also questioned, at military barracks in Chichester, the Argentine “Blond Angel of Death”, Lt Commander Alfredo Astiz, who was brought to Britain as a prisoner of war in 1982 during the Falklands conflict. France and Sweden wanted Astiz over the disappearance in Argentina in 1978 of two French nuns, said to have been tortured, and in 1977 of a young Swedish woman.

Britain, concerned to observe the letter of the Geneva Convention, which allowed Astiz as a POW to say nothing, considered it impossible to extradite him. He was swiftly repatriated, and would be jailed for life for murder in Argentina in 2011.

Reece had lived through the trauma of violent death and sudden loss at the age of eight. His father, John Reece, a miner, was killed in an accident with machinery underground at Silverwood Colliery near Doncaster, South Yorkshire, in 1938. Reece thereafter vowed to do what he knew his father had wanted for him: that he become a soldier in a Guards regiment, or a police officer.

Reece did his National Service from 1947-49 as a trooper in the Royal Horse Guards (now part of the Blues & Royals), including a posting to Germany, before joining Hastings Borough Police Force, later part of Sussex Police, in 1951. The family moved after the accident to Hastings in East Sussex, where Reece’s mother’s sister lived. Elsie Reece, who went on to marry a former Scots Guardsman, Harry Ellison, in 1941, opened a guest house at St Leonards on Sea, and Reece and his only sibling, his brother Peter, waited at table.

The boys went sailing and fishing, and Reece, always fearless, would collect gulls’ eggs from the resort’s bomb-damaged pier. Peter also joined Sussex police, becoming a superintendent. Reece married a local girl, Daphne Hyland, in 1953. They had no children. Reece’s wife and brother survive him.

In retirement Reece became Chairman of the National Federation of Sea Anglers. In 1996 a letter he signed as NFSA chairman in protest at the Sports Council’s then exclusion of angling from the top 22 sports, was read out in the House of Lords. Until March this year he was President of East Hastings Sea Angling Association. He collected 6,000 books on angling, many of which he presented to the Hastings club, and on the walls of his home in Hastings displayed many models of fish, and sometimes the real thing.

The similarity between detective work and angling was not lost on Reece. “You get the right bait, you catch the fish; the bigger the bait the bigger the fish,” he once told friends. He was awarded the Queen’s Police Medal in 1986, the year he retired.

Reece’s biggest fish caught in the non-policing world was a six-gilled shark recorded by Fishing Digest as weighing 485kg, or 1,069lb 3oz, a European record, off the Azores on 18 October 1990.

John Frederick Reece, police officer: born Thrybergh, south Yorkshire 20 April 1929; QPM 1986; married 1953 Daphne Mary Hyland; died Hastings, East Sussex 2 November 2015.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments