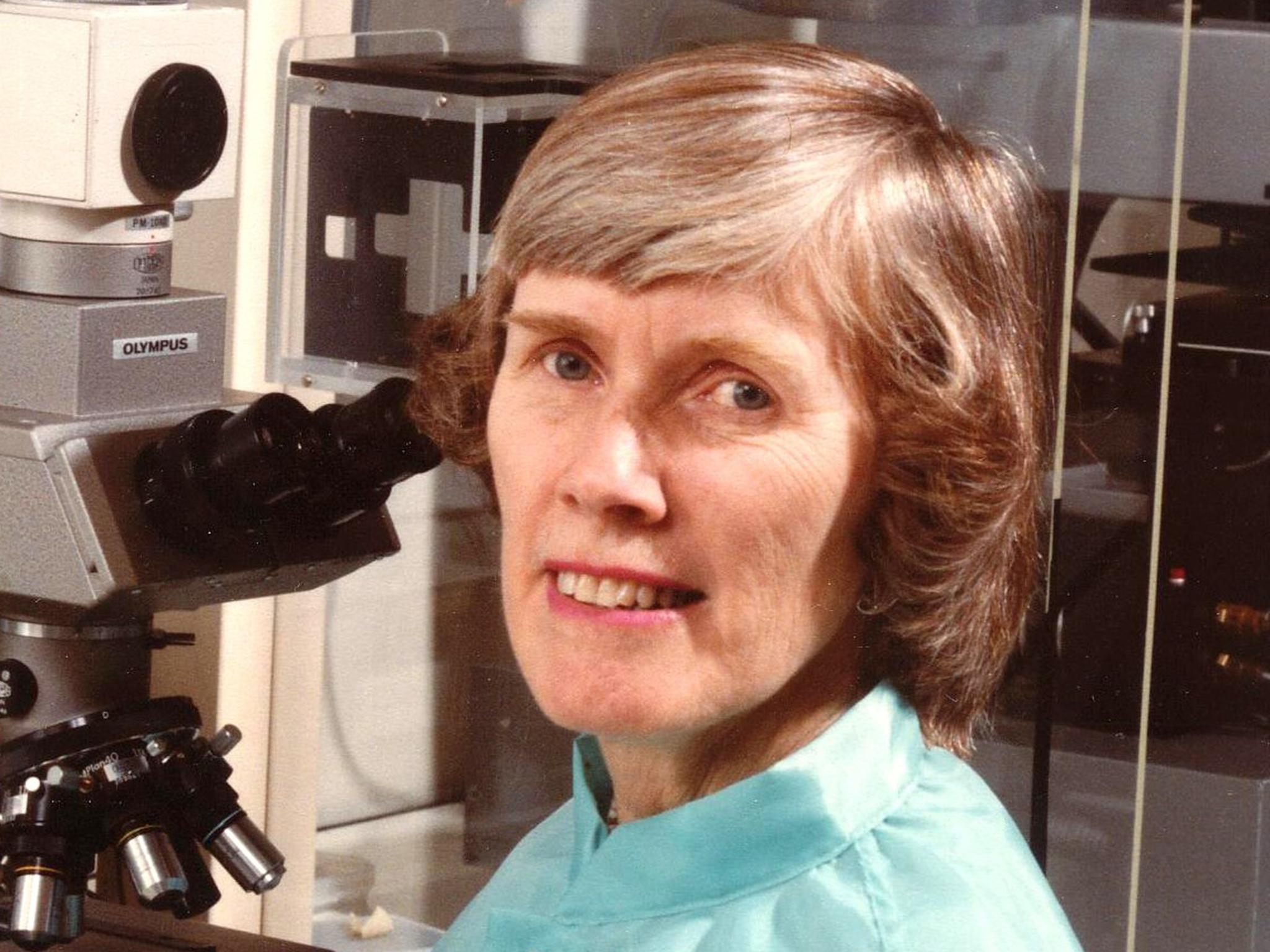

Frances L Lloyd: American scientist who played a key role in developing an international voltage standard

She worked on crucial stepping stones on the road to achieving a programmable quantum voltage standard with virtually zero uncertainty that non-experts could use

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Frances L Lloyd, who has died aged 94, conducted groundbreaking research in science and technology and was the fabricator of the key element in a device used around the world for measuring one of the fundamental quantities in modern life: the volt.

A vast effort has been made to create exact, precise and unchanging units of measurement for all the quantities that support every aspect of our lives. The volt, basic to all of the electrical and electronic devices surrounding us, is one such quantity.

Lloyd’s great contribution was in the development of a precise and unchanging standard for its magnitude. Such a standard makes it possible for a volt in one laboratory, one country or one computer, to be exactly the same as any other.

Working at the National Institute of Standards and Technology’s (NIST) laboratories in Boulder, Colorado, from 1977 to 1989, she was a key member of a team that developed what is sometimes called the “reference volt”. It was part of a modern system of standards that, with progress in science, enabled laboratories to replace physical objects or chemical reactions as the fundamental quantities of measurement.

(The reference volt depended on the relationship between the volt and constants of nature that are regarded as immutable. Through a phenomenon called the Josephson effect, microwave radiation beamed onto a superconducting device called a Josephson junction can produce a voltage output)

Microwaves of precisely known frequencies could be beamed onto intricate, identical and perfectly formed microelectronic chips to produce precise, identical voltages.

A group of scientists at the NIST labs in Boulder designed a Josephson device that used superconducting microchips similar to the semiconducting chips used in many of today’s electronic devices.

Lloyd started at the NIST lab in 1977. It was just the right time, according to Clark A Hamilton, who was a member of the superconducting electronics group that developed the reference volt equipment.

“A lot of people made contributions to the design of the equipment,” Hamilton added, but Lloyd “was the one to take that design and turn it into an integrated circuit chip.” The chip had 20,000 Josephson devices on it, he said, “and every one had to be perfect.”

Nobody else, he said, “had been able to do it at that level.”

Her skill with integrated circuit layout and fabrication was something that she had learned “from scratch” after joining the lab, according to Hamilton. The chips that he helped design “and that Frances made” are used in the standards laboratories of 70 countries, he said.

The Josephson-effect device has been credited with revolutionising the measurement of high voltages.

In 1989, Lloyd shared the US Commerce Department’s Gold Medal for contributions to voltage standards.

Frances Lytle Lummis was born in Honolulu in the early 1920s. She accompanied her father on his assignments as a US army officer, spent part of her youth in the Philippines and completed high school in Spartanburg, South Carolina.

She was a Duke University studying physics when she took leave during Second World War to help design aircraft propellers in a special programme, the Curtiss-Wright Cadettes, that recruited women in science to aid in the war effort.

Lloyd received a bachelor’s degree from Duke in 1946 and a master’s degree in physics from the University of Virginia in 1948. She then moved to the Washington area to work at the Naval Ordnance Laboratory.

Her marriage, to Richard Lloyd, ended in divorce. Her son, a urologist at the University of Colorado and the Veterans Affairs hospital in Denver, is her only immediate survivor. He lives in Denver.

Throughout her career, her son said, Lloyd was “well aware that people thought women were maybe a little less capable.” Not interested in conflict or drama, he said, she was “not there to prove anything. She just wanted to do physics.”

After a while, he added, “people would see that she was okay.”

Frances L Lloyd, scientist, born 4 September 1923, died 23 March 2018

© Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments