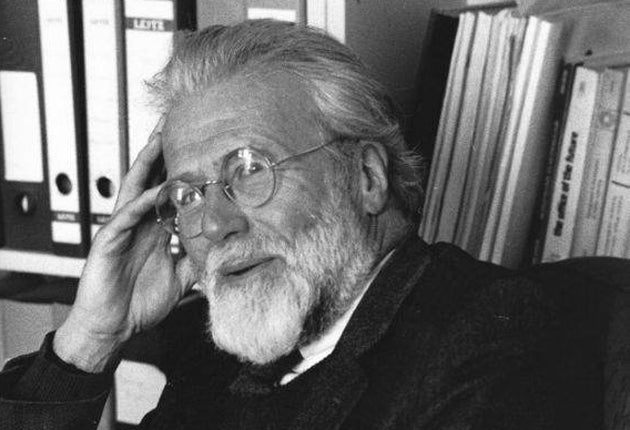

Alan Milward: Economic historian celebrated for his analyses of the post-war European project

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Alan Milward was an influential historian of European affairs whose work and opinions, both distinguished and controversial, challenged both those in favour of the European project and those opposed to it.As an economic historian he was always prepared to immerse himself in the driest statistical minutiae. But he also relished challenging existing orthodoxies, for example on the Marshall Aid plan for rebuilding post-war Europe.

He was, in short, both a meticulous analyst and a cheerful debunker. His friend, the Harvard professor Charles S Maier, who is writing a book entitled Alan S Milward and a century of European change, spoke of "his ferocious archive-based specificity, lucid intelligence, and remorseless questioning of accepted pieties."

An example was his view of the Marshall Plan, under which the US pumped millions into Europe in an operation credited as the key to the reconstruction of the ravaged continent. Maier recalled that he and Milward, while not wishing to reduce the plan to insignificance, "sought to remove the mythology and reverence that surrounded it." They did not believe it was ungenerous, but felt it should be examined "soberly and without sentimentality".

Milward's attributes were described by the author Martin Westlake, who spoke of him as "brilliantly counter-intuitive", recalling that he first met him "when he was a brilliant professor with a twinkling eye and I was a penniless student." Westlake summed him up: "He was a master of archival material but he brought his material to life with his wit and command of language. He was an incisive speaker at any conference, wearing his great learning with equally great modesty." The economic historian Christopher Smout added, "His histories of the Second World War profoundly shaped our awareness, his insight into the forces that shaped contemporary Europe upturning many a cosy apple-cart."

Alan Steele Milward was a grammar school boy born in Stoke-on-Trent in 1935, the only child of a post office worker. The family was not well off, especially when his father was absent during the war. He took his degree, a first in history, at University College, London, followed by a doctorate at the London School of Economics. He went on to lecture in Britain and overseas. At one point he had a spell at the School of Oriental and African Studies teaching Indian archaeology: he explained that he had an early interest in applying the methodology of economic history to archaeology.

A holiday in Norway and Finland stimulated an interest in Scandinavia. He also had the huge asset of a gift for languages, becoming fluent in Norwegian, German, Italian and French, a range which proved invaluable as he delved into European history.

Much of his very substantial early output consisted of books on the Second World War, dealing with Germany as well as France and Norway. In one work he argued that only in 1942, after it became clear to Hitler that he could not quickly achieve the conquest of much of the world, did Germany devote all its economic energy to the Nazi war machine.

Milward later concentrated his attention on the post-war period, his views on the Marshall plan generating much controversy. A colleague remembers "heated discussions arising from his zest for taking on economists who met his broad-brush contentions with incredulity."

He believed that the evolution of today's EU was shaped not by grandiose goals of fashioning a federalised Europe but by the more prosaic and practical national interests of its members. His theme was the continuing vitality of national politics and national communities. He mocked as "European saints" figures such as Jean Monnet and Robert Schuman, who put forward visions of an idealised unity, insisting instead that national calculations and interests prevailed over the international, and that domestic political advantage trumped the international.

He had little time for what he saw as shallow thinkers, proclaiming with exasperation that "it would be wonderful if a new historical understanding could put an end to the hollow clanging of cliches hurled around the media by politicians and journalists."

Over the course of his life his output was prodigious, as was the number of colleges where he taught and indeed the number of former students who maintained a life-long admiration for him. His workplaces included Stanford, UMIST, LSE, St John's College, Oxford and, twice, Florence. A member of innumerable boards and committees, he was elected a fellow of the British Academy in 1987.

In 1993 he accepted an invitation from the Cabinet Office to write the official history of the accession of the UK to the European Community, and relations between the country and the Community up to the mid-1980s. He delivered the first volume but not the second, as illness brought to an end the work of a figure who combined academic rigour with a fresh eye and a sense of inquisitive mischief.

Alan Steele Milward, economic historian: born 19 January 1935; married 1963 Claudine Lemaître (one daughter; divorced 1994), 1998 Frances Lynch (one daughter); one other daughter; died 28 September 2010.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments