The use of sonic ‘anti-loitering’ devices is breaching teenagers’ human rights

Here’s what can be done

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.How would you feel if your right to freedom of movement was infringed because other people your age were involved in criminal activity? You would be outraged, and rightly so. Yet, this is the reality facing teenagers and young people as Scottish railway network ScotRail introduces the Mosquito anti-loitering device at two of their stations.

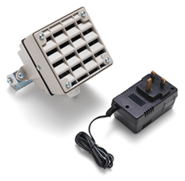

In an effort to move young people on, the Mosquito emits an unrelenting high-frequency sound which affects those under the age of 25, who have the capacity to hear high-pitched sounds in a way that older people, whose hearing is gradually declining, do not.

This move is in response to recent criminal activity committed at Hamilton and Helensburgh stations by groups of youths. However, the use of such devices targets all young people, regardless of their behaviour.

The device deliberately discriminates, exploiting biological vulnerabilities which young people cannot do anything about. According to the inventors, this is a “safe” sound which relies upon the irritation it causes as a way of getting rid of youngsters when they are “loitering”, and therein lies its aim.

Compound Security, the company which developed the device 12 years ago, maintained in an interview (listen in at 6:50) with BBC Radio Scotland that its target market is not domestic homeowners, but it is possible for anyone to go online and purchase one of these devices from as little as £345.

Problem kids

The company markets the device by referring to “problems with kids and teens” who are “damaging property, hanging around in rowdy groups, littering, smoking and drinking, playing music…” The language used by Compound Security, such as describing the device as having the “teeth to bite back at these kids” arguably attempts to demonise young people, and suggests that only a hostile approach to them “hanging about” – surely a benign act – can prevent such behaviour.

But the anti-social problems this device seeks to prevent are not unique to those under 25. There are plenty of adults who are guilty of such behaviour. When criminal activity is involved, the police should be called. Devices such as the Mosquito encourage people to take the law into their own hands “without confrontation”, according to Compound, while inadvertently infringing the human rights of all those under 25.

ScotRail maintains that the devices are having a positive effect which has led to a reduction in incidents at these two stations. But this does little to ease the disquiet of the Scottish Commissioner for Children and young people themselves, such as the Chair of the Scottish Youth Parliament, Amy Lee Fraioli, who believe that the device constitutes indiscriminate targeting of young people.

Put simply, these devices are breaching the rights of our young people. We all have human rights, regardless of race, sex or age. These include the right to a private life, free movement and peaceful assembly under the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR). While it would be unthinkable to have practices that hinder the exercise of such rights by black people or women, for example, the same sense of outrage doesn’t appear to apply to those under 25.

Children’s rights

As well as being protected by wider human rights conventions, such as the ECHR, those under 18 also have additional, special protections under the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC).

The deployment of the Mosquito infringes a number of rights enshrined in the UNCRC, including: the principle of non-discrimination (article 2); the principle that the best interests of the child must be a primary consideration in all decisions affecting them (article 3); the right to express views and influence decision making in all matters affecting them (article 12); the right to freedom of assembly and association (article 15); the right to protection from violence, abuse and injury (article 19); and the right to play, leisure and recreation (article 31).

In 2010, the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe found that the use of the acoustic devices to disperse children and young people is a disproportionate interference with their rights under article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights, which includes the right to respect for physical integrity. Their use may also interfere with article 11 of ECHR which guarantees the right to freedom of peaceful assembly. The use of acoustic pain may also be a breach of their rights under article 3 of ECHR to be free from degrading treatment.

The Scottish Commissioner for Children strongly condemns the use of mosquito devices. Backed by calls (see paragraph 37) from the United Nations itself, the Commissioner argues that this type of device suggests that children and young people are unwanted in society.

The way forward

There needs to be greater work done to bridge the gap between adulthood and childhood and to challenge the negative stereotypes that are perpetuated about teenagers. Deploying devices such as the Mosquito isolates an entire generation of under 25s who know that they are perceived to be a nuisance. This cannot be positive, and only widens the gulf between young people and adults in society.

With 2018 designated the Year of Young People in Scotland, this would be the perfect opportunity for concerted efforts to actually engage with young people. Of course criminal activity is not acceptable in any situation, but anti-social behaviour and so-called loitering by youths suggests that young people have nowhere to go, which is the real problem here. Only with proper dialogue can we begin to address their issues and concerns.

Let them tell us, in their own way, why they are “loitering”, what they think would help reduce anti-social behaviour and ultimately, how we can all work together to promote a well-integrated society. A social media campaign could start the ball rolling, asking the questions and encouraging young people to participate in finding the answers.

As wise old Albus Dumbledore proclaims in Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Askaban: “A child’s voice, however honest and true, is meaningless to those who’ve forgotten how to listen.” It is time to open our ears to something that we can all hear – if we choose to.

Tracy Kirk is a PhD student in law – child and adolescent rights at Northumbria University, Newcastle. This article was originally published on The Conversation (www.theconversation.com)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments