How early Arctic explorers survived starvation, scurvy and months of boredom

Almost 500 years ago, whaling expeditions to Svalbard forced a band of polar explorers to get creative to survive in the harshest winter on the planet. Mick O'Hare tells their story

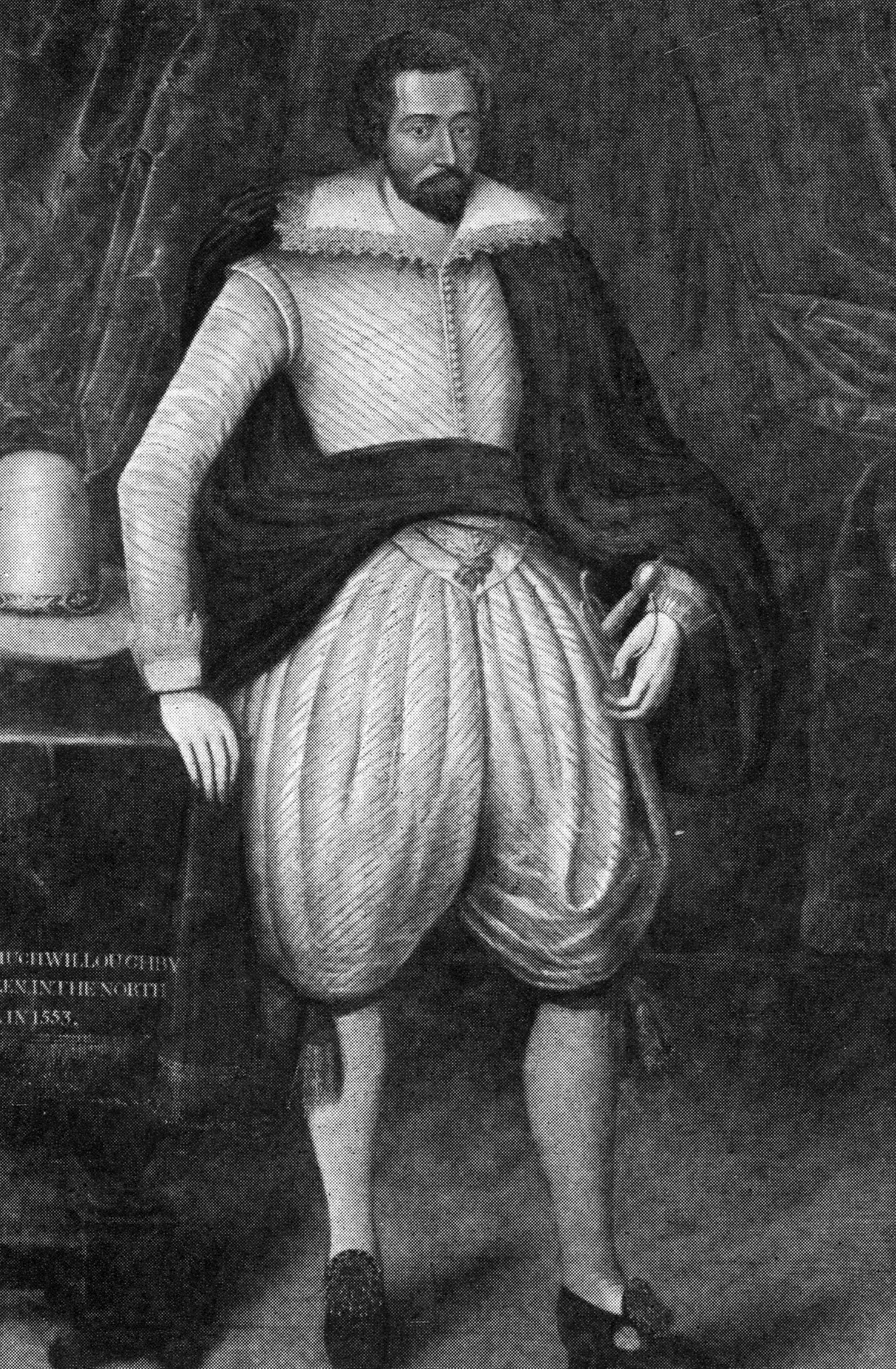

In 1553 English explorer Hugh Willoughby attempted to live through an Arctic winter. He and his crew of 62 were the first non-native humans to try. It was not out of choice. Willoughby had been the leader of an expedition of three ships attempting to find a northeastern route from Europe to the far east and the trading opportunities they hoped to secure there. Two of the ships, including the one captained by Willoughby, never returned, although their journals describe what befell them.

Separated from the third ship and using ambiguous maps and unreliable instruments, they became trapped in a bay off the Kola Peninsula of far-north Russia as the sea froze around them. Their equipment was rudimentary, their clothing inadequate. Their bodies were found by fishermen the following spring. Some had frozen to death ridden with scurvy, others were apparently poisoned by carbon monoxide from stoves as they attempted to insulate the ship from the ravaging cold outside.

Where Willoughby failed, Willem Barentsz – after whom the northern sea between Russia and Norway is named – succeeded (just). The Dutch navigator also had no intention of spending the winter above the Arctic Circle. Yet 43 years after Willoughby, he too became stuck in the ice off the coast of the Russian island of Novaya Zemlya while searching for a northeastern route to the east. Five crew members died but 12 survived by spending time both aboard the ship and on land, building a wooden lodge for shelter. They were resourceful and fortunate.

They also learnt much, most of it disagreeable. They were the first explorers to discover that in such freezing conditions human skin would burn before the heat of a fire could be felt. They began sharing bunks to sleep and taking warmed cannonballs to bed with them. Water and, possibly more troubling, beer and wine casks burst and Gerrit de Veer, the party’s carpenter who kept a log, noted that fixing wooden vessels and building shelters became almost impossible because the nails would freeze to your fingers or lips before they could be hammered in. Entries in log books frequently described the weather as a “white hell” or “the worst storm yet” but although Barentsz himself died on the homeward journey, they were the first non-native Arctic dwellers to survive a winter with no sun.

Both Willoughby and Barentsz were inadvertent over-winterers and there would be others, but possibly motivated by both the success of Barentsz – whose experiences provided vital lessons for those wanting to survive in such extreme conditions – and an eye on commercial opportunities for those prepared to run the huge risk, others began to consider spending the long months of Arctic winter in the far north. The Svalbard island archipelago to the north of Norway had long been regarded as prime whaling territory. English seafarer Jonas Pool’s expedition to Svalbard in 1612 described “ploughing through whales” so plentiful were they. Anyone prepared to spend the winter there would have a head start on more cautious whalers who waited until the spring before setting off for the Arctic.

Those considering the possibility may also have been inspired by the story of eight English deer hunters unintentionally left behind at Bellsund on Svalbard’s largest island Spitsbergen in 1630 when their ship departed without them. Stricken with scurvy, malnutrition and frostbite, they somehow survived without specialist clothing and shelter. Perhaps whalers who arrived fully prepared could do the same. Could the benefits of living at the very fringes of human capability outweigh the obvious risks? Certainly there were people prepared to try – Svalbard’s fjords were deep, perfect for whaling ships, and close to waters teeming with whales, seals and walruses. And demand for whale products – from oil to soap, paint and candles to corset supports – was growing throughout Europe. Blubber was big business. For anyone who could start working earlier in the season there would be substantial rewards. But the journals of those who eventually opted to risk their lives and their sanity enduring the harsh winter for the most part speak only of frigid misery, privation, dread and peril.

British and Dutch companies were to the fore, bringing with them Basque whalers who had honed their prowess over centuries working the Bay of Biscay and as far afield as the Canadian coast. “Spitsbergen was one of the most accessible places in the Arctic and a site of whaling since the 17th century when companies began to set up stations around the coastline,” says Michael Bravo, historian at the Scott Polar Research Institute in Cambridge. The stations were in use in summer only but in 1633 seven whalers from the Dutch Noordsche Compagnie volunteered to stay at Smeerenburg (Dutch for “Blubbertown”) over the winter, to protect their properties from raids as well as get that all-important head start.

Smeerenburg was on Amsterdam Island just off the northwest coast of Spitsbergen, and was a place of fable, a mythical Arctic Shangri-La. Many who had never visited and never would believed it to be a heaving metropolis full of whale processing stations, bawdy lodging houses, gambling dens, taverns and brothels, but that was far from the truth. In reality it had a summer population of just over 200, boiling blubber in iron and copper kettles and processing whale carcasses in what was a drab settlement of small plants, storehouses and dwellings tucked between desolate mountains, much like other whaling stations dotted about the Svalbard archipelago. Even summer life was a struggle – the workers brought coffins with them knowing that dangerous work or scurvy would claim some of their number. Founded in 1619 it would be abandoned by 1663 after the once multitudinous whales around Spitsbergen had been hunted to oblivion.

Another seven whalers chose to stay on the island of Jan Mayan, but while the Smeerenburg group survived, the one on Jan Mayan did not, and nor did a second Smeerenburg group the following year. Conditions described by both survivors and those who succumbed were horrendous. Minus 20C was common throughout January, February and March with minus 40C or below not unknown. The chill factor of the incessant wauling winds made it seem colder still. And as De Veer in the Barentsz party noted, it could start snowing as early as August.

Furnaces had to burn continuously so huge supplies of wood (on islands with few trees near the coast) and coal were needed, meaning the air was thick with choking, fuliginous residue but, although damaging to lungs, that was survivable. What wasn’t was lack of water. Butts placed next to the furnaces still froze solid – the fires could not even melt the permafrost on which they stood. One journal entry noted that “you either burnt the stocking on your feet right through the flesh to the bone, or you had frostbite and lost your toes that way. There was no state of an in-between. It was a terrible choice.” Amputations were commonplace as fingers, toes and then feet and hands succumbed to frostbite. “My companion once had a nose,” wrote one man. “Now the wind blows into the front of his bitten face.” The whalers attempted to trap Arctic foxes for fur with little success.

Even if the men could survive the freezing conditions, their diet, or indeed lack of it, would likely hasten their demise. It’s probable that scurvy killed some whalers before they froze. Arctic archaeologist Tora Hultgreen, director of the Svalbard Museum, says the whalers would have arrived in Svalbard for the summer season after a winter in their own countries without fresh vegetables and fruit. By the time they volunteered to overwinter in the Arctic they would have gone a year without vitamin C. “Their uniform diet of salt meat or fish and dried peas was always likely to prove fatal,” says Hultgreen. “And the irony is whale meat contains vitamin C but nobody chose to eat it.” Not that the cause of scurvy was known in the 1600s. The whalers tried any number of quack cures such as smearing tobacco juice and ash onto their bleeding gums or rubbing bear fat into sore joints, obviously to no avail.

Yet it’s possible that the first Smeerenburg group of Dutch whalers under the leadership of Jacob Segersz van der Brugge, who survived the winter of 1633-34, got lucky. They collected a plant to eat, Cochlearia officinalis, which contained vitamin C – in fact it’s now known as scurvygrass – and it’s likely this, rather than favourable meteorology that saw them survive. They were doubly lucky, they scattered it in an outhouse which freeze-dried it, rather than letting it rot. They also killed reindeer for fresh meat while the other overwinterers were either unsuccessful or more inept hunters. Fresh meat contains small amounts of vitamin C and it’s significant to note that the eight English hunters and the Barentsz party all managed to catch animals for food. Maybe it was just enough to see them through.

The Novaya Zemlya effect

In January 1597 Gerrit de Veer, the carpenter on Willem Barentsz’s mission, noted that he had seen the sun appear over the horizon even though the party was enduring the long polar winter night. He was the first person to witness a mirage now known as the Novaya Zemlya effect. The mirage relies on light refracting through the differing thermal layers of the atmosphere and presenting a flattened image of the sun despite it still being below the horizon.

For those that failed the journals tell of painful, swollen joints “just to move a leg brought out bruising” and bleeding gums; “sometimes a man could lose five fingers of teeth awaking in the morn”. Internal bleeding, usually betrayed by bloody faeces, was the beginning of the end. Bones would crack and connective tissue fall away. “It would have been more solicitous to shoot the stricken,” says one journal entry. “But what man would have such a iniquitous heart?”

For the party that died on Jan Mayen island there was a further cruel twist. They had trapped a bear for meat but postmortems showed that they contracted trichinosis – a parasitic roundworm – from it, probably by inadequate cooking. Agonising infection of the muscle tissue and overwhelming fatigue meant they were unlikely to be able to venture far to set traps for other animals meaning scurvy would soon follow.

So insufferable cold and scurvy were the twin scourges facing both the parties that survived and those that succumbed but sitting astride those tortuous bedfellows was the subliminal torment of first boredom and then depression. “How often did we recount the same stories?” asked one. Van der Brugge wrote of the “continual repression of confinement and overcrowding” and the “lack of sun to lift the spirit”. Without strict patterns of sleeping, waking and eating, a human’s diurnal rhythm was easily broken by the endless polar night.

Interestingly Van der Brugge insisted on maintaining the daily routines his men would expect at European latitudes. He was well aware of the curse of idleness. There were regular activities and penalties – missing breakfast or a suspension of the brandy ration – for oversleeping. “If you could survive the cold and the ravages of scurvy, there was still the psychological hell to endure,” says Herbert Blankesteijn, a Dutch journalist who has written extensively on Arctic history. “Van der Brugge encouraged games, trips out in favourable weather and hunting parties. Despite limited space indoor activities were also an essential part of the day.” Jacob van Heemskerck of the Barentsz overwintering reported doing the same. His group, of course, survived.

There was more than boredom to counter though. Both the surviving groups at Bellsund and Smeerenburg spoke of hallucinations, some of them collective: “We all saw the devil’s fleet of ships out in the bay,” says one diary entry. “We would lay an extra place at the table for the devil because we knew he would be sharing supper with us.” “It was thrice ‘H’,” wrote another. “Homesickness, hunger, hopelessness”. The ice would creak, the misunderstood phenomenon of the northern lights would play across the bowl of the seemingly endlessly darkened sky before the blizzard would descend. For people who believed in a god to fear, why wouldn’t they expect the devil to soon be planting his foot on their doorstep?

But maybe religion played another role. Aside from regular prayer (most often “begging for survival”) and bible reading being an essential part of Van der Brugge’s strategy of ensuring the men maintained their diurnal rhythm, Louwrens Hacquebord, retired archaeologist, geographer and former head of the Arctic Centre of the University of Groningen in the Netherlands, has pointed out that there was a notable difference between the religiosity of those who survived overwintering and those who did not. “The English at Bellsund redoubled their prayers when under the greatest stress,” he says. “And the journals of the group who survived the first overwintering at Smeerenburg noted their pious observance of Sunday, Christmas and saints days.” In contrast the groups who failed to survive did not. Assuming no divine intervention, Hacquebord believes that religion provided daily routine and structure, and the celebrations offered both unity and a goal to be achieved. Perhaps psychology was as important as sanctity…

After the deaths of the second group of Smeerenburg whalers it would be a long while before more volunteers risked overwintering and by the mid-1660s the raison d’être was in any case removed. The ruthless exploitation of the whale population around Svalbard had made it impossible to locate any species within reach of the coast and whaling moved out into the open Arctic sea using boats that could process the carcasses without having to drag catches to shore. Since the decline of commercial whaling, bowhead whales have returned to the waters of Svalbard but it’s believed that perhaps as few as 8,000 exist.

In the meantime, trappers moved in when the whalers moved out. The first were Pomors from Novgorod who exploited Arctic foxes and polar bears for fur and walruses for meat, fat and tusks. They were used to brutal Arctic conditions and, unlike the Europeans, were capable of surviving winters in Svalbard. Crucially, they knew too how to avoid scurvy. They were followed by Norwegians, to whom the archipelago now belongs. They learnt their techniques from the Pomors, although many still died – their graves are dotted about the landscape of the archipelago as are the archaeological remains of various whaling stations. Eventually mining in the last century led to Svalbard gaining its first permanent communities and more recently Spitsbergen became home to the Svalbard Global Seed Vault, which preserves samples of seeds from all over the world to ensure their survival in the event of any future global catastrophe.

Some trappers and hunters overwinter in Svalbard today, away from the permanent settlements and mainly for recreation which would doubtless come as a surprise to the likes of Barentsz, Willoughby and Van der Brugge. Courageous, incompetent, unfortunate, foolhardy – these are all words that have been used to describe those early attempts to survive a winter in the Arctic. Perhaps pioneering, in its purest sense, might be a more apt and impartial description. Pioneering and very definitely gelid.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments