From Bristol to LA: The anti-gentrification posters sweeping through our cities

In Bristol last year, notices appeared with a slogan hitting back at hipster hotspots and playgrounds for the rich. Since then, areas like Peckham and Frome have taken the message on as their own

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

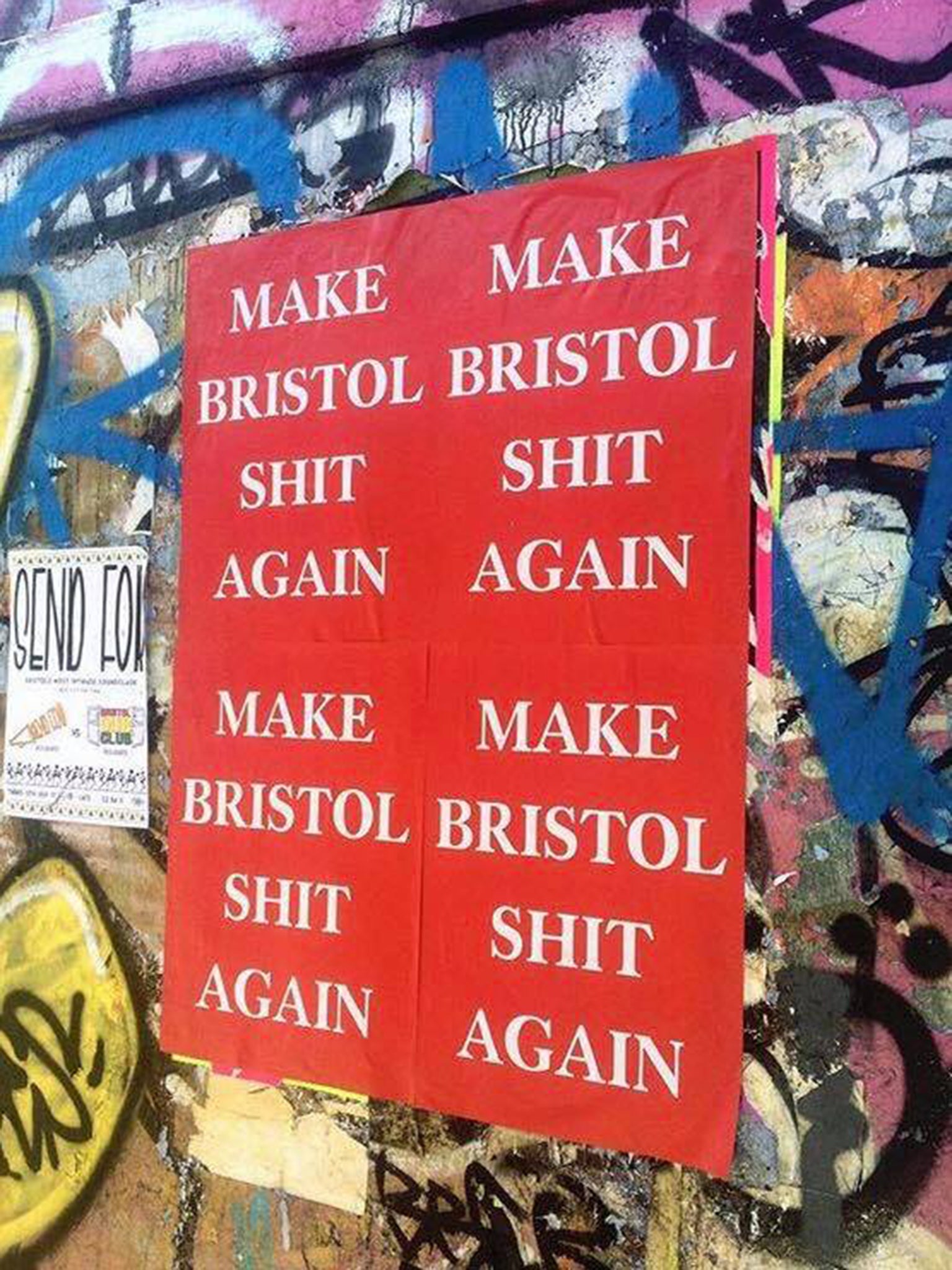

Your support makes all the difference.Last summer, stickers and posters began to appear on the walls of Bristol. In a gnomic parody of Trump’s “Make America Great Again“ they read “Make Bristol Shit Again”, and were plastered over the city’s gentrifying high-tide areas, such as Stokes Croft and St Pauls.

The city talked. Vice magazine did a piece about it, and MBSA went viral as both an exemplar of the city’s mordant humour and a plea against gentrification.

“My hometown is becoming an extension of London, and losing its crappy edge,” wrote Vice’s Angus Harrison in a bittersweet excoriation of Bristol’s new-found glossiness.

MBSA might have been a one-off valedictory howl, but in an act of synchronicity, other “Shit Again” activity arrived.

In Peckham, the southeast London district previously known for being the location of Only Fools and Horses and latterly for being a hipster hotspot, a “Make Peckham Shit Again” landed in March, as did a Twitter account called “Make Frome Shit Again” along with a few MFSA hashtags of the same vintage. (In an odd circularity, much of Only Fools and Horses, although set in Peckham, was actually filmed in Bristol.)

Then, this spring an international brigade of “Shit Again” warriors in Los Angeles in the form of “Make Venice Shit Again” (Venice the hippyish LA district, to be clear, not the Birmingham of Italy).

Such was its clout that Hollywood actor Josh Brolin sported a MVSA baseball cap, part of a local atmosphere so heightened that a recent LA Weekly story found cause to lament that in Venice, “You’ll sooner find a $200 (£150) wool poncho than a $12 pair of flip-flops.”

So the “Shit Again” tag somehow hit the mark, both as a lament to the new and deracinated world of overpriced and socially exclusive development, and as a great merchandise idea in its own right. So there’s a MBSA hat, T-shirt and even “laptop skins”, while MVSA baseball caps retail at $30 and MPSA baseball caps a snip at a tenner.

As Tumbleweed Parker puts it (not his real name) his Make Peckham Shit Again hats were a response to Trump’s MAGA cap as well as a way to protest the gentrification of Peckham, which has deep roots but has gathered pace in the last five years as a domino in what you might call the “de-shitting” of London.

“Before Trump I’d been thinking about doing some merchandise to kick back against all the happy-clappy local pride movements that seemed to spring up after the London riots in 2011,” says Parker.

“It’s delusional to think London’s the best place in the world when its homegrown youth are so desperate to burn it down, and Sadiq Khan’s idiotic marketing of London is used to sell it off to developers.”

Moreover, he adds, “people can’t afford to live in this so-called paradise”. So in its own way, the hats and T-shirts are a kind of Situationist protest or, as he puts it, “a barricade against the unhelpful narrative that Peckham is, was, or ever could be a great place for property speculators. I think it’s important that we say, it’s actually not that great.”

***

So is this ‘Shit Again’ activity really a hankering for the days of shuttered high streets without good coffee: a kind of “Fings Ain’t What They Used to Be” for disgruntled millennials? Possibly: the creator of Make Bristol Shit Again, Bristolstreetwear, bears the legend “Say no to sourdough” on its website, and certainly, there’s a sense of loss about gentrification’s march through the neighbourhoods: the sticky-carpet pubs turning into homes, the chain stores pushing out independents, and £3-a-cup flat whites and avocado-on-spelt ousting the chipped mug of tea and sausage sarnie.

The protestors are also needled by endless proclamations of arrival, such as Frome’s topping the charts as a good place to move, and Bristol winning The Sunday Times’ “best place to live in the UK” gong: the kind of boosterism that gives some locals the impression their towns are forgotten backwaters just itching to be discovered.

It’s rattled further by development that piggybacks on existing “bohemian” infrastructure, such as Stokes Croft in Bristol, where the loss of artist-occupied warehouses and office blocks like Hamilton House have sparked long battles.

Yet perhaps there’s something else afoot too: a nostalgie de la boue for the old townscape of sticky boozers and crap shops where people supposedly felt a sense of belonging.

The term “gentrification” was minted in 1964 by British sociologist Ruth Glass with reference to Islington, then attracting the middle classes into areas full of multi-occupied late Georgian and early Victorian houses, where they set about losing the net curtains and exposing the floorboards, hence the contemporary jibe, “stripped pine-eers”. Indeed, today’s neo-gentrifiers still like their decoration “raw”, although these days it’s more about bare bricks, old shops and and cocktails in jam jars. And there has long been a missionary-like flavour about the process, whereby gentrifiers comes into an unreconstructed urban district, “discover” it anew and turn it into a mirror of their own taste.

But the idea of what gentrification constitutes has shifted, says Loretta Lees, a professor of human geography at the University of Leicester and author of several books on the matter, including Planetary Gentrification. “I’ve noticed that anti-gentrification has become more performative in the last two to three years,” says Lees. “The traditional class aspect of it has given way to a more complicated scenario, full of internal conflict, where critics of gentrification are often gentrifiers themselves and where the discussion is more about consumerism more than class.”

The 2017 book Gentrifier by John Joe Schlichtman, Jason Patch and Marc Lamont Hill also works this theme with a look at how gentrification is now commonly used as a means to describe clothing choices, food and art, often centred around the cipher-like figure of the “hipster“ and part of a battle for the authentic soul of a place.

“Imagined realities and physical realities collide in gentrification,“ they wrote. This aspect became apparent in 2015, when a demonstration against a branch of the Cereal Cafe in London’s Brick Lane bought a sense of pantomime to the debate, while in 2016 Montreal’s local government introduced a by-law that no more than one in six businesses can be a restaurant: a move that has been seen as a way of moderating gentrification.

So the new symbols of gentrification – the cortados, chachka shops and themed restaurants – began to seemingly represent a force that was making Bristol want to be shit again, as well as rippling out anxiously to other corners of the country. It’s a phenomenon that Lees says has seen “gentrification move on from key world cities to rural areas, market towns and ‘edge cities’ – places on the margins of urban areas”. One of the key differences between the Ruth Glass era and now is that gentrification has been globalised and also exists in miniature.

The Twitter author of “Make Frome Shit Again” didn’t want to be outed: it’s a small town after all. But local conservationist and project manager Katy Duke is happy to discuss the way Frome has become a victim of its own success: a factor often seen as part of the gentrification process. “In common with many places people can’t afford the property in Frome any more,” she says. “But it also manifests in a tendency to look at local things like [luxury hotel] Babington House, coffee and gift shops as somehow causative.”

As for Frome becoming “shit again”, she says that the actual long-term locals want a post office, a good supermarket and a Peacocks: all things that might not be the grails of a “down from London” person’s eye.

There’s also a streak of self-deprecation that runs through a certain British mentality, as seen in Crap Towns, the 1990s hit, bringing the “declinism” of the 1980s up to date. Then, things could only get worse. And surely gentrification can sometimes be good? Lees draws a moral distinction between the “gentrification that displaces people, and the good regeneration that keeps people in place”, but struggles to think of a good example of the latter.

In 2015, research from the US magazine City Lab concluded that gentrifying neighbourhoods don’t actually lose low-income residents at a substantially lower rate than any other neighbourhood. Plus, it should be said, there’s nothing gentrifiers scorn more than other gentrifiers. It’s fun to have a pop.

Perhaps “shit again” means affordable housing and a regaining of convivial civic life, or perhaps it’s an aesthetic of urban decline. Whatever, a “shit again” cap is the perfect self-abnegating gift for an uncertain age. “It seems to be resonating with a lot of people who feel alienated by the discourse of positivity around urban redevelopment, which is most people I know,” says Parker. “Even the local estate agent ordered one. I hope he wears it when he hangs himself.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments