Independence and a currency union may not be compatible for Scotland

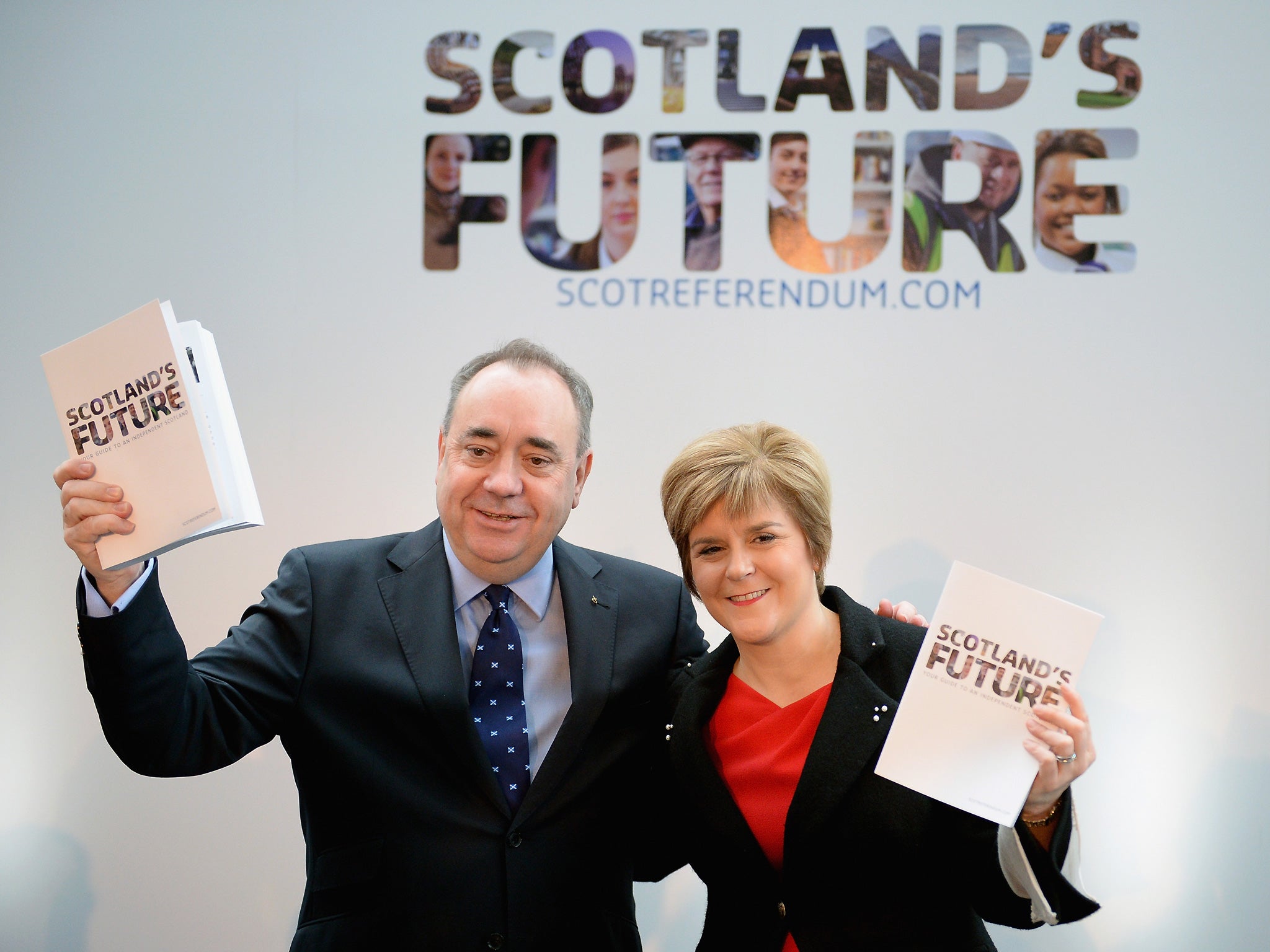

My week: Mr Salmond’s plan is to share the pound in a sterling zone with the rest of the UK, but this idea is not proving popular in the Treasury

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Other than what Usain Bolt may or may not have said about the Commonwealth Games taking place in Glasgow, the event has been a resounding success. And not only from a sporting perspective, but a political one too. Hosting a global gathering with such brio just a few weeks before Scotland’s independence vote can only strengthen the nationalist cause, even if most business leaders I talk to think – and hope – that a break-up of the Union will still be narrowly voted down.

Drowned out by the crowd’s cheers at Hampden Park, an important intervention in the debate over Scotland’s economic future went largely unnoticed south of the border. In a newspaper article this week, Sir Andrew Large, the former Bank of England deputy governor, and ex-Prudential chairman Sir Martin Jacomb argued that the Scottish First Minister Alex Salmond was deceiving the electorate over plans for a currency union in the event of a “yes” vote.

Their stance is that keeping the pound, “through a currency union like today”, is not compatible with political independence. If Scotland’s economy outperforms the rest of the UK, as the Scottish National Party believes it will, then all will be fine. But if it does not, Sir Andrew and Sir Martin point out that things can go awry because Scotland will not have the levers to regain competitiveness through currency devaluation. The eurozone might have worked better if its members had given up more of their independence; the economic woes of the Club Med countries over the last few years show what happened when they did not.

The duo suggest that Scotland could use the pound without formal agreement, as with Kosovo and the euro, or peg a Scottish pound to the UK pound, but they highlight the potential downsides of Scotland having no influence over interest rates and needing to build up its own multibillion-pound currency reserves. Mr Salmond’s plan is to share the pound in a sterling zone with the rest of the UK, but this idea is not proving popular in the Treasury.

Meanwhile, Royal Bank of Scotland warned again yesterday that a yes vote could hit the group’s credit rating and prospects. In March, Mark Carney, the Bank of England’s Governor, suggested that independence might prompt RBS to move its headquarters to England.

It is unavoidable that this referendum will be decided by hearts, not minds. But how risky it is that the real economic negotiation can only happen after the 18 September vote.

Crises and scandals prove the City lacks a fear factor

It was two summers ago that Marcus Agius and Bob Diamond resigned, respectively, as chairman and chief executive of Barclays in the wake of the Libor-rigging scandal. Only this week, Lloyds Banking Group was hit with fines of £217m of its own for doing precisely the same thing. Not only is the clean-up of past misdemeanours painfully slow, but in revealing that Lloyds traders also manipulated the price of the bank’s own taxpayer bailout, it still has the capacity to plumb new depths.

In plotting a financial recovery, the Prudential Regulation Authority’s Andrew Bailey has concerns over the costs of misconduct holding lenders back. The trouble seems to be that fines and refunds are not holding banks back enough.

It is clear that the cultural change that has been promised by the City will only come to pass if it is underwritten by law. Fresh rules on bonus clawbacks are welcome as long as London is not competitively disadvantaged against New York or Singapore. However, reckless banking is a criminal charge that corporate lawyers insist is exceedingly hard to prove.

What the City lacks is a fear factor. As if any more evidence were needed of Britain’s patchy record in white-collar crime, the grovelling apology and payout of £4.5m to the Tchenguiz brothers shows how off-target the Serious Fraud Office is. Starved of funds, is there much prospect of it doing better?

Even the Financial Times opined that it is “absurd and destructive of public confidence” that senior bankers haven’t been held to account for their part in the financial crisis. Of course prosecutions will not be easy to bring. But that doesn’t mean the authorities shouldn’t have tried much harder.

A British technology star thinks big at Arm’s length

If Simon Segars feels the pressure of leading Britain’s top technology company, it didn’t show when I met the chief executive of Arm Holdings for a drink this week.

It’s been a year since he took the reins of the chip designer from his former colleague Warren East. Arm still looks unstoppable, despite rival Intel casting jealous looks at its dominance of the smartphone market. To demonstrate how the market has accelerated, of the 50 billion chips that Arm’s partners have shipped in the last two decades, a fifth of them were shipped in 2013 alone.

Now Mr Segars is concentrating on bringing the “Internet of Things” to life – and demonstrating the value of a chip-enabled spin dryer or fridge. Meanwhile, politicians bend his ear to ask how more Arms can be created in Britain.

Thinking big from the outset is crucial. However good Arm’s engineering might have been, it wouldn’t have taken off if its early bosses hadn’t got on a plane to sell it. Even now, Mr Segars is notionally running from California a company best associated here with the brainpower of Cambridge.

To keep that clear, international perspective, it could be better for business if he doesn’t come back.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments