Hamish McRae: Ultra-cheap money is not sustainable, and we'd better prepare for the inevitable

Economic View: We have barely begun the march back to normal interest rates - another seven years of pull seems a reasonable outlook

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Should we fear higher interest rates, or welcome them? We are going to get them for sure, and the faster growth picks up, the sooner the higher rates will come. That is quite clear. But once you get into the specifics as to the timing, speed and nature of the increases, then the picture becomes much harder to discern. But since they are coming, we had better get used to the idea.

The first thing to remember is that a central bank has a high degree of control over short-term interest rates – in the UK set by the Bank of England – but progressively less influence the longer the term. So official rates have remained at 0.5 per cent since the banking crisis, but the 10-year yield has moved around a lot. It was above 4 per cent when the Coalition took over, fell to below 1.5 per cent last summer, rose to more than 2 per cent, dipped to 1.7 per cent a few weeks ago … and now is back up to 2.4 per cent. But if you are trying find a "normal" level for yields, you might choose something around 4.5 per cent, which would give a 2.5 per cent real return with inflation at 2 per cent.

Currently yields are still depressed by quantitative easing, and the Bank of England now holds more than one-third of the national debt. At some stage it will have to sell that debt back to proper savers, because all monetary experience shows that if you don't, you end up with more inflation. You can justify QE on the grounds that the banking system is so damaged that to maintain a reasonable flow of lending you have to offset that damage in some other way. But there are costs to artificially low interest rates, and eventually these outweigh the benefits.

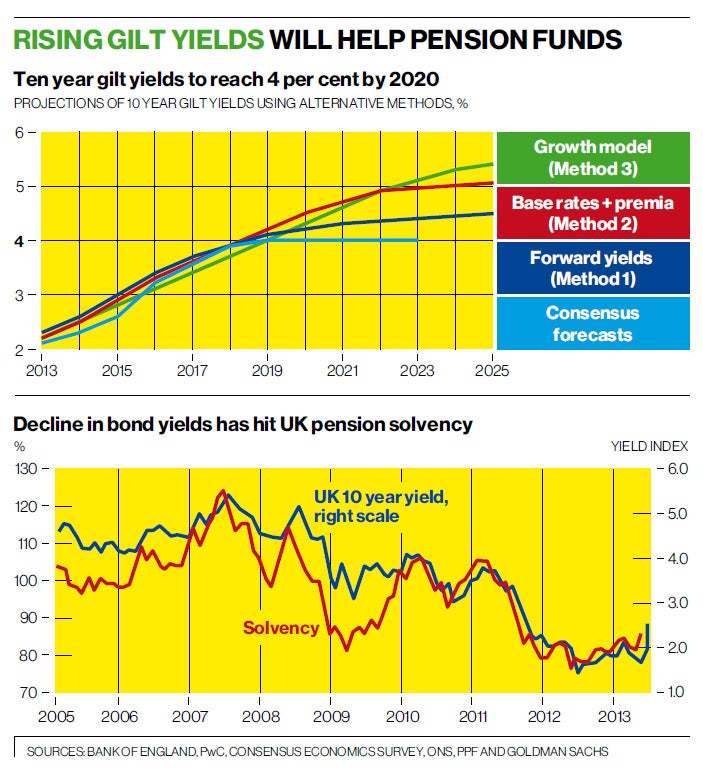

There is a new study out today from PwC that looks at the likely path of bond yields in rather more depth. You can see some projections for 10-year gilt yields in the top graph. The bottom one, from Consensus Forecasts, is what people in the markets expect if you ask them. The next one up is calculated by looking at forward yields, what investors in the market actually trade money at. The next one looks at what might happen to base rates and then adds a premium on top of that. Then the top one looks at what is expected to happen to nominal GDP (ie money GDP, not real GDP) and the relationship between that and gilt yields in the past.

The thing I find most interesting here is that up to around 2020 the different methods of calculation all have pretty much the same result. Beyond then they vary, but as a working assumption, the idea that long-term interest rates will be back to normal levels by then seems pretty sensible. So if that is right, what are the implications?

The first thing is that borrowers, including governments, will benefit from historically cheap funding for several years yet. There may be some disaster round the corner – look at poor old Portugal having to borrow at 8 per cent – and I find it hard to think through what the break-up of the eurozone might do to long-term rates more generally. But we have barely begun the march back to normal interest rates, and another seven years of pull seems a reasonable outlook. If that is right, it gives everyone several years to adjust.

It will take that. First we have to end QE – we almost certainly have in Britain, but the US Fed only begins to taper off its purchases of Treasury securities later this year. Then we have to start increasing base rates, say some time in 2015. And then after that, the official holdings of government securities, here and elsewhere, will have to be sold back to the public, with a start being made, I guess, around 2018. This will be "overfunding" the deficit, such as remains of that, and the lower the deficit, the easier it will be to sell down the backlog.

Will higher interest rates be a headwind to growth? It is a huge question, and we don't have much experience of it. We have the experience of high interest rates in the 1980s, when they were used to control inflation, and we have the return to normal ones in the 1950s, after the cheap money of the 1930s and 1940s was finally reversed. But while the 1930s in some ways resemble the present, mercifully the 1940s do not. What does seem clear is that very low interest rates have not boosted demand as much as was expected, so it may be that reversing that policy will not cut demand much. And there will be countervailing forces: it may even be that higher rates will increase demand.

One way in which that might happen is demonstrated in the bottom graph. Goldman Sachs has looked at the impact of higher yields on company pension funds, showing as you can see that the fall in gilt yields has damaged pension solvency. Lower yields have cut annuity rates and therefore had a mathematical impact on the size of the pension pot needed to fund any particular level of payout. The combination of higher gilt yields and decent equity returns is just what is needed to push pension funds back to solvency. Pension regulators are increasingly recognising that shifting back to equities is a prudent move for funds to make. Money needed to top up pension deficits is money not available for investment.

More generally, it may well be that availability of funds is more important than price. That might apply to individuals as well as companies. Would easier access to slightly more expensive mortgages boost or reduce demand for home loans? We don't know. But what we do know is that ultra-cheap money is not sustainable, so we had better get ready for the inevitable rise to come.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments