‘Everyone leaves a footprint’: How I used my rough upbringing to build a career tracking criminals

Quantexa founder Vishal Marria speaks to Andy Martin about the moment he realised big data was the key to catching money launderers, fraudsters and sex traffickers

Young Vishal Marria went to “the roughest school in south London”. He was surrounded by a lot of knife-wielding delinquents and criminals in the making. But he always turned up early at school. And he always did his homework. And he never got individual detention either. He still has the certificates at home to prove it. He’s got stacks of GCSEs and A-levels.

Amazingly, he managed to keep out of harm’s way. How? “It’s all a question of anticipating trouble before it hits you. You have to spot patterns of behaviour. I learned that early on.” Now, aged 37, as CEO and co-founder of Quantexa, he has made a career out of spotting patterns of behaviour – or misbehaviour – around the world.

His father came by boat from India in 1961 and landed in England with only one shilling in his pocket, but worked 20-hour days to acquire a number of cash-and-carry shops across London. “While other kids went home from school,” says Marria, “I went to the cash-and-carry.” He started work aged six or seven, stacking shelves and talking to customers.

He went on to take a first-class degree in Computer Science at Royal Holloway, part of the University of London, and a master’s with distinction. He joined BAE Systems and then became, at 28, the youngest ever director at Ernst and Young. It was when he working on “compliance” with the professional services firm (which effectively means “non-compliance”: if everyone complied in the first place you wouldn’t need compliance), that he had his big insight.

“I was consulting with banks like HSBC, Deutsche Bank and Morgan Stanley. What I realised is they were all trying to make decisions based on a small amount of data. You wouldn’t buy a house by looking through the letter box, would you?” Marria argues, quite reasonably, that if you’re buying a house you walk through the door and check out the kitchen and the bathroom and all the bedrooms. And then you check out the local crime rate and the schools too. It’s what he calls “internal context” and “external context”.

The same applies if you’re trying to track down the bad guys. Those who are not big on compliance. We are no longer, a la Sherlock Holmes, looking for the footprint in the flowerbed, not even fingerprints or DNA. Individuals are good at concealing their identities. But if nearly all crime is now a conspiracy, criminals can be exposed at the level of the network. Quantexa – founded 3 years and 7 months ago – offers to connect the dots to nail fraudsters, money launderers, and human traffickers. The name Quantexa, the founder explains, contains “quantitative analytics” and “exabyte” ie a quintillion bytes.

The major banks I was consulting with were all trying to make decisions based on a small amount of data. You wouldn’t buy a house by looking through the letter box, would you?

“It’s all about relationships”, says Marria, and gives a simple example. Suppose four people in a single vehicle are claiming for whiplash injuries from an insurance company. Which could amount to around £30,000. If you look only at the details of the individual claims, then it might well appear legitimate. Whiplash is practically impossible to disprove. It could be genuine. But when you see multiple claims coming from individuals whose names differ very slightly, but all using the same credit cards and the same bank accounts, then you can start to think in terms of a crash-for-cash scam. “You have to look at a lot of different signals – patterns show up in the data. If I look for one person I won’t see it. We’re looking for the gang.”

Vishal Marria bought his first property at the age of 18, but he still lives at the same house in south London that he grew up in. He makes tea with his father first thing in the morning (he has his tea English-style, his father has some more complicated Indian-style tea, involving spices and a lot of boiling, plus milk and sugar, and half-hour meditation), and he takes his daughter to school. Then he drives along the same road he used to walk to go to school, and comes to work and sets about investigating sex or drug trafficking, for example.

Marria is a crime fighter, working with insurance companies, banks and government, but it’s nothing like Hawaii Five-0 or Inspector Morse. The one thing that connects all the crimes he mentions is financial transactions. They all involve money changing hands.

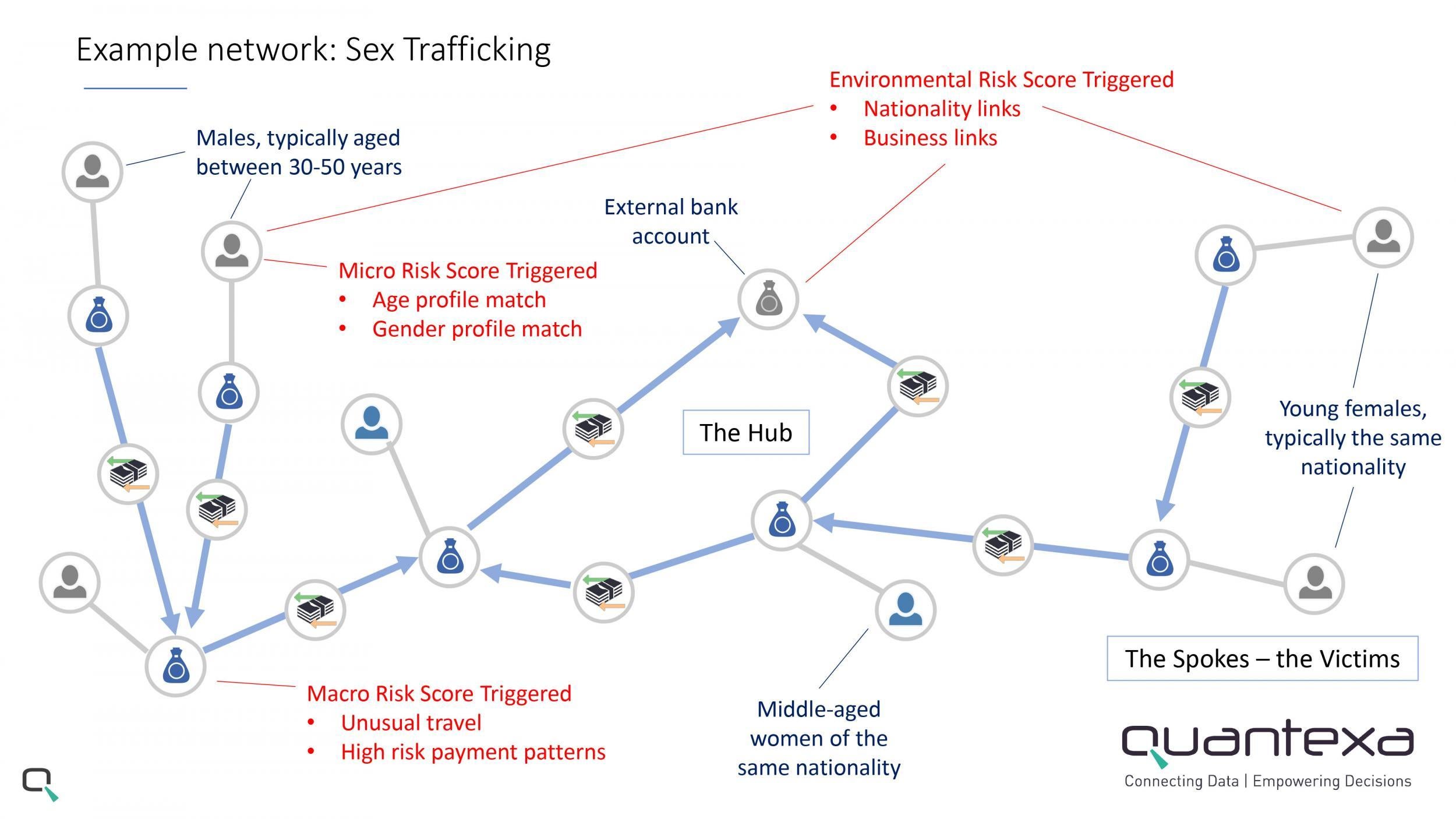

He gives me an example of the kind of data network involved in sex trafficking. There are a lot of micro alarm bells that can be set off: males associating, aged between 30 and 50 years; young females, typically of the same nationality. But a “macro risk score” is triggered by the connection with “unusual travel” and “high-risk payment patterns”. In effect, organised crime leaves discernible traces, like tracks in the snow, and his job is to establish the links. “Everyone leaves a footprint, from going to work to committing a crime.”

A whole bundle of data sets can be relevant, from names and telephone numbers to corporate registry data. But it’s not all about quantity of data, in the end. “You can have all the data in the world,” says Marria. “But there is a point beyond which you don’t need more information. You have enough. Your system can still pick out an event.” Which is when the AI sends a message: “Dear human, this is a case worth investigating.” Marria says that they don’t knock on the door in pursuing criminals, but they do provide the intelligence. “When you knock on the door to arrest someone you need to know who is in the house.”

At some point Marria realised that in capturing all this data about large populations, “we can identify good customers as well as the bad guys”. So Quantexa can pick out the compliers from the non-compliers. It awards certificates for the kids who play by the rules and do their homework as well as handing out detentions.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments