‘Every walk is about a different idea’: Richard Long on the art of seeing the world

The pioneering land artist speaks to William Cook about the many miles he has travelled – from Alaska to Lapland, the Andes to the Himalayas – and the joy it brings him

In an upstairs room at the Lisson Gallery in London, Richard Long is telling me about his new one-man show. He’s matter-of-fact, but if you’re not familiar with his artworks his words may need some explaining – for this is a man who virtually created his own art form.

Is he a sculptor? Is he a photographer? Is he a poet or a painter? He’s all these things, and more. He’s been making art for half a century, yet even after all these years his work still feels like something completely new. “I realised that art could be made by walking,” he says. “That brought time and distance into a work – and once I realised that, I had an amazing freedom to make work on an enormous scale.”

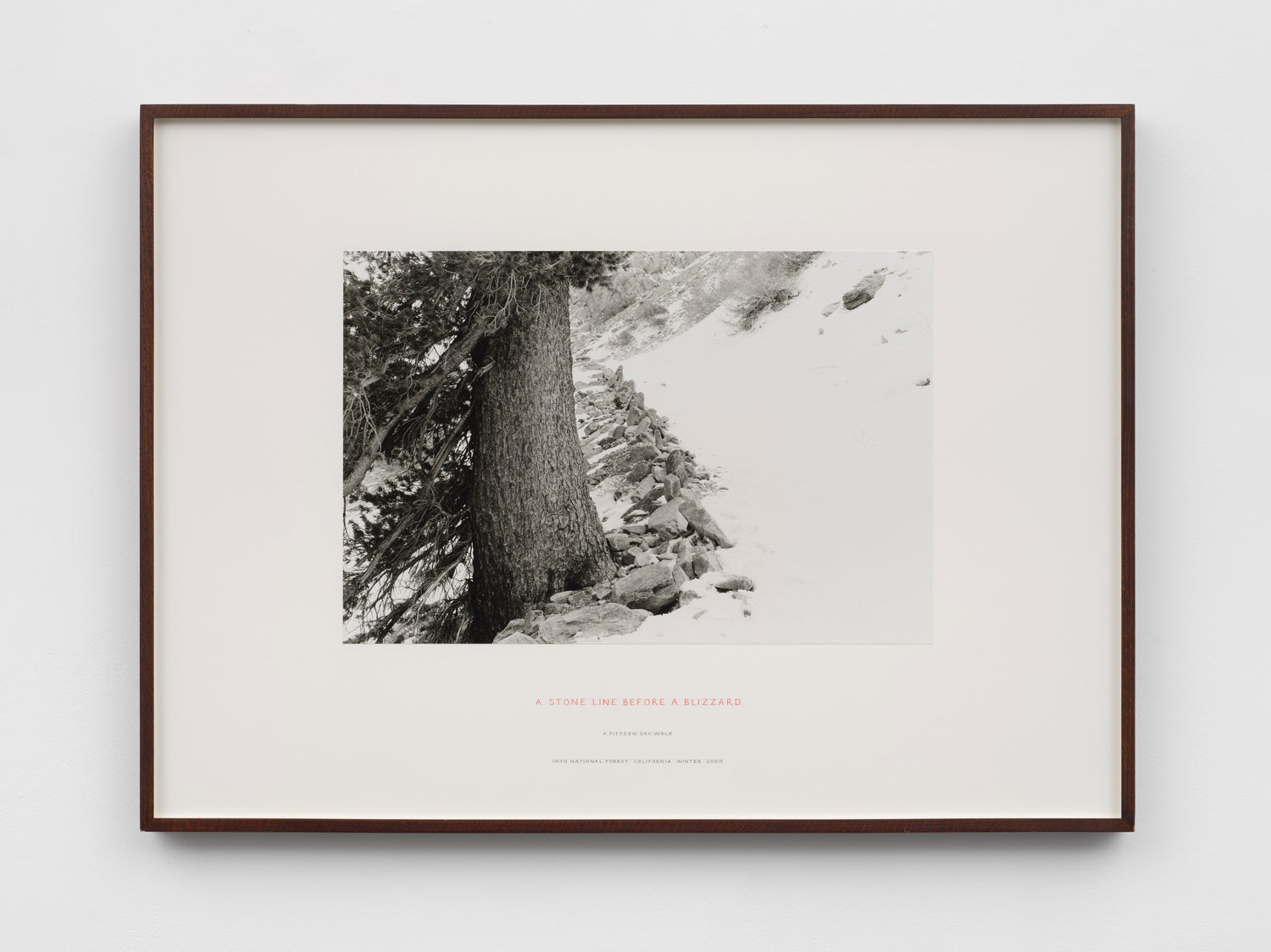

Most of Long’s artworks consist of short descriptions or photographs of solitary walks he’s undertaken – over long distances, in remote places, in Britain and around the world. Often, he makes simple sculptures in the landscape he travels through, from natural objects that he finds en route. A stone circle is his favourite motif. Yet these sculptures are incidental, rather than the central activity.

“I often say that if a work in the landscape takes more than about half an hour to make, there’s probably something wrong with it,” he told the curator Lucy Badrocke. “Quite often, I have the urge to make a sculpture and then the need to keep on walking takes over.” What makes walking so alluring? “It’s the best way to see the world,” he tells me. “It’s a different type of attention, a different scale.”

His pioneering work has won him widespread acclaim: the Turner Prize in 1989, a CBE in 2013 and a knighthood in 2018, but there’s nothing grandiose about him. As Nicholas Logsdail, the founder of the Lisson Gallery, observes: “He’s happiest when alone outdoors with a rucksack on his back.” Spending so long outside in isolated places has shaped his body and his temperament. Walking has kept him fit, of course. His voice is quiet yet forceful. He chooses his words with care.

Rather than reshaping the earth in his own image, he leaves a light footprint. The sculptures that he makes on his travels aren’t meant to be preserved for posterity. Their precise locations remain unclear, so they’re very rarely visited. They’re mostly very difficult – nigh on impossible – to find. Some of them are spectacular, but most of them are surprisingly subtle and discreet. Some may last for centuries, others may only last a few weeks.

Long doesn’t seem to mind much either way. For him, making these sculptures is all about being in the here and now, in a particular time and place. What happens to them afterwards is of no concern to him. They’re not monumental monoliths, like Stonehenge, erected to last for all eternity. They’re more like sandcastles, waiting to be washed away by the incoming tide. “A water drawing can dry in the sun in five minutes, but a stone on the roadside could last another thousand, two thousand, ten thousand years,” he explains. “The stones that I leave along the way, they don’t disappear. They exist in people’s minds because they know about it as my work.”

Usually, his photographs are the only evidence that these sculptures ever existed. Sometimes, he doesn’t even take a photo – he simply writes a short account of the walk he made. He’s an excellent photographer, and his descriptions of his journeys are poetic, but the description and the photograph are both secondary. “The world outside the studio was far more interesting for me,” he says. “Clouds or grass or rivers or rain, the whole territory of the landscape.” The main artwork is the walk itself.

Long also makes sculptures for permanent display in galleries and sculpture parks, and one of these sculptures, called Rhythm and Blues, is included in this show. They’re a lot like the sculptures he makes on his travels, typically stone circles, but even though they work well in isolation, to me they feel like relics of previous journeys or signposts of journeys yet to come.

Many of these journeys are truly epic in their size and scope. This show alone, comprising 20 artworks, encompasses journeys in Arizona, Argentina, Iceland and China. A lot of these treks entailed mammoth amounts of walking – hundreds of miles in total, often 20, 30, even 40 miles a day. “I can make many works on Dartmoor or Exmoor, but then I can make a work in the Antarctic,” he says. “Everything is usable. I feel very free to make work anywhere.”

Inevitably, at the age of 77, some of the marathons he used to do are no longer feasible. “I walk slower now,” he says. “Obviously, I’m not as fit as I was. I can’t believe some of the mileages I did when I was younger!” Yet these journeys, great or small, weren’t mere excursions or endurance tests. There was something else going on, something more profound and elemental. There’s an atavistic element – living the life of the nomad, the wanderer, closer to the way we used to live.

“Richard reminds us that life can be more straightforward than our modern existence,” says Nicholas Logsdail. “There is a little bit of all of us in Richard’s work.” There’s something intensely spiritual about his sculptures, something that evokes the timeless majesty of the landscape, the fragility of nature, the fleeting trajectory of human life. His work isn’t overtly religious, but it’s reminiscent of religious ritual – the retreat into the wilderness, the pilgrim on his lonely path.

But despite its potent mysticism, his work is never wilfully obtuse. “It’s also a celebration. It’s about beauty as well – about beauty of ideas and beauty of places, about the beauty of the planet.” Walking and camping are things he enjoys tremendously, and that enjoyment is infectious. He makes you want to put on your walking boots and follow in his footsteps. “A lot of my art is actually based on things that give me pleasure.”

Long’s journeys make connections with the rhythms and patterns of the natural world, connections that were familiar to our ancestors, but which have become far removed from the frantic bustle of our urban lives. There are numerous examples of his deep affinity with nature, but one artwork in this exhibition sums it up. It’s called Walking at the Speed of Spring, from Spring in Cornwall to Spring in Caithness. “A south to north walk of 1030 miles in 33 days,” reads his sparse description, “starting from the Lizard on April 2 to ending at Dunnet Head on May 4.”

That was 24 years ago, when Long was in his early fifties - over a month of constant walking, averaging over 30 miles a day, a phenomenal mileage for a middle-aged man. Yet even today, in his late seventies, he’s still racking up some impressive distances. Another artwork in this show, called Daffodils Along the Way, chronicles a nine-day walk he made this year, across England from west to east. This walk took him from shore to shore, across moors and dales, through Lancashire and Yorkshire, but his description doesn’t chart the route so much as the things he saw and heard: the dawn chorus, a full moon, a starry night sky…

![Long: ‘[My artwork is] about beauty of ideas and beauty of places, about the beauty of the planet’](https://static.independent.co.uk/2022/11/16/11/LONG700002_001.jpeg)

He also includes more humdrum stuff – a drystone wall, a missed turn – but there are two phrases that leap out at you, “Sometimes You Don’t Need to Go Far,” and “More Road Behind Me Than the Road Ahead.” Long has made art on every continent, including Antarctica, but the title of this exhibition, Drinking the Rivers of Dartmoor, references a more familiar landscape, a lot closer to his West Country roots. The title refers to a trek he made last year: “A six-day walk around some of the headwaters of my life.” Today, with a lot more road behind him than ahead, it feels like coming home.

“Since 1969, Dartmoor has been my studio – I’ve used Dartmoor in many ways,” he says. “I like the idea that I’m probably the first person to walk across Dartmoor in a straight line. It interests me to do something original like that. I’ve also made works about water on Dartmoor – I made a walk in a certain area where I use all the riverbeds as footpaths. Then another work was to walk around Dartmoor carrying a stone from one river to the next river, so it was a combination of the rivers and the stones.

“And then that got me thinking – all my life, all my walks, have taken me to places where, obviously, I can walk, but also where I can find water. So then I thought, ‘Well, I’ve been walking on Dartmoor all my professional life and drinking the water of Dartmoor.’ And then I had the idea to make a walk specifically focusing on that very idea – of drinking the rivers.” Hence the title of that work, Drinking the Rivers of Dartmoor, which became the title of this show.

They’re not monoliths, like Stonehenge, erected to last for all eternity. They’re more like sandcastles, waiting to be washed away by the incoming tide

He was born in Bristol in 1945, the eldest of three children. His father was a primary school teacher, his mother was a homemaker. It sounds like a happy childhood, playing on the Downs, and along the banks of the River Avon. “The Avon gorge, and the towpath, and the cliffs and the screes – that was my childhood playground,” he says. “My parents gave me a lot of freedom to roam around.” Buried in a deep, steep valley, the Avon is one of the world’s most tidal rivers, and the sudden shift from low tide to high tide is dramatic. Long’s childhood was comfortably suburban, but this river was a prelude for the rugged landscapes of his artistic life.

Long excelled at art from an early age – he only ever wanted to be an artist. “It was always my language, really – ever since I was a tiny little boy,” he says. “I was always the school artist, ever since my first infant school. I had my own easel when I was five years old.” His parents recognised his passion for art, and nurtured it. “They decided to redecorate our front room, and they took the wallpaper off, and instead of putting new wallpaper back on, they said, ‘You can make a big mural on the wall,’ which I did.”

At primary school, he had a “wonderful” headmistress, who spotted his talent and allowed him the liberty to develop it. While his classmates were singing hymns in assembly, he was left alone to paint. His secondary school was similarly supportive. “I used to be the boy who’d paint all the scenery for the school plays,” he recalls. “I had a very enlightened art master. In my last year, before I went to art school, they let me come in every day in the summer holidays and I painted a big 45-foot mural in the dining hall.”

In 1962 he went to West of England College of Art. In his second year, he won the painting prize. In his third year, they threw him out. “I think I was just too precocious,” he says. “I was doing very experimental, environmental work.” For a lot of youngsters, such an emphatic rejection would have been a huge blow, but this apparent setback didn’t shake Long’s self-belief in the slightest. “It was the luckiest break in my whole life!” He didn’t know anything about the art world, but that became a blessing. Right from the start, he always followed his own path. “I was extremely absorbed in my work.”

Long did a string of odd jobs, including working in a paper mill, applied to various art schools and won a place at St Martin’s School of Art, one of London’s most prestigious – and progressive – art schools. Here, the sculpture course was led by the innovative sculptor and teacher Frank Martin. He recruited top sculptors like Anthony Caro and Eduardo Paolozzi as teachers. Above all, he trusted his pupils to follow their instincts and find their own way through. “He had a fantastic nose for oddball students.” It was here that Long met Hamish Fulton, a fellow pupil who became a good friend and collaborator, sharing his passion for making art out of walking.

Long got his first big break while he was still at art school when his groundbreaking artwork, “A Line Made by Walking”, was bought by the Tate. The concept was extremely simple. Hitchhiking between London and his home in Bristol, Long stopped off in a nondescript field and walked back and forth in a straight line until his footsteps produced a path of flattened grass amid the upright grass around it. He took a photo of it and departed.

This field was nothing special. There was no reason to visit it, and even if you wanted to you’d be hard-pushed to find it. The line in the grass was nothing special, and by the time anyone saw the photo it would have long since vanished. “The fact that it then disappeared was neither here nor there.”

Long’s photo of the field was fairly perfunctory, yet this rudimentary image was revolutionary, creating an entirely new concept of what makes an artwork, the first page of a new chapter in the history of modern art. “I knew what I was doing was important. That was the time when people just made art for the glory, or for the love ideas. It was a time when we could reinvent the art world in completely new ways - making art in new ways. That’s what we were interested in – not selling it or making money.”

Long soon attracted the attention of leading gallerists, in Britain and abroad. His first exhibition was at Konrad Fischer’s influential gallery in Düsseldorf. “I went over on the boat,” he recalls, “and I came back with two hundred quid in my back pocket.” What a great feeling, to know that other people, strangers in another country, actually got it! “I knew it was a good work I’d made, a good exhibition, but it was a revelation to me that if you’re in the right place at the right time, then you’d meet people who’d also understand what I was doing and would buy it.” He used the money to go to Tanzania and climb Kilimanjaro, leaving a sculpture at the summit.

During a career of nearly 60 years, he’s trekked all across the planet, from Alaska to Lapland, from the Andes to the Himalayas. “Every walk is about a different idea.” In Iberia, he made a walk called from Crescent to Cross, walking across Spain and Portugal from the Great Mosque of Cordoba to the Cathedral at Santiago de Compostela, connecting two histories and two religions, a trek that took him 18 days. In South Africa, where the bones of the earliest humanoids were discovered, he made a series of walks called Making Footprints in the Cradle of Humankind, echoing mankind’s migration out of Africa. As the filmmaker Werner Herzog said, “The world reveals itself to those who walk.”

A lot of great artists have produced great art from a position of great unhappiness. Richard Long seems to me to be that rare and precious thing – a great artist who’s discovered how to live a happy life. Is that accurate, I ask him? Well, up to a point, he says. “I’m happy making my work, but sometimes I’ve had unhappiness in my private life,” he tells me. “Real life, or personal life, is very different from the life of making art.” He’s been married and divorced. He has grown-up children. “I’m just a normal regular guy.”

Yet I still can’t shake the thought of him striding alone across those empty landscapes. Unlike most of us, Richard Long found a way to live the life he wanted to live and make the art he wanted to make, and to me that seems heroic. “It’s the only thing I can do, and it gives me pleasure,” he says, modestly. “I like the idea of being original – doing things that other people haven’t done before.”

Richard Long: Drinking the Rivers of Dartmoor is at Lisson Gallery, London NW1 (www.lissongallery.com) until 23 January 2023

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments