Tarantino wants to stop making movies – but that’s just self-wrecking vanity

The filmmaker says he’s going to quit after one more film ‘because I know film history and from here on in, directors do not get better’. But is that really true? Geoffrey Macnab investigates

Quentin Tarantino hasn’t yet reached 60 but is already looking to pension himself off. The director who began his career with such ear-razing chutzpah in his debut feature Reservoir Dogs (1992) will make one more movie, his 10th, and then call it a day.

“You’re too young to quit. You’re at the top of your game,” chat show host Bill Maher protested to Tarantino last week, but the director stuck to his guns. “That’s why I want to quit!” he exclaimed. “I know film history and, from here on in, directors do not get better.” He has already been working for 30 years (“that’s a really long career”), he explained, claiming he has “given it everything I have”.

But is there any truth in what Tarantino said? Is it downhill all the way after you hit 60?

This year’s Cannes Film Festival (regarded as the showcase for the best in world cinema and starting next week) would imply otherwise. You’ll find several directors far older than Tarantino in the festival’s main competition.

Paul Verhoeven is still going strong at the age of 82 with his new lesbian nun movie, Benedetta, finally ready to be shown. He isn’t letting such mild inconveniences as hip surgery hold him back and has already moved on to new projects, such as a TV adaptation of Guy de Maupassant’s Bel-Ami.

The festival opens with Annette, the latest feature from Leos Carax, once considered the young poète maudit of French cinema but now a greying figure in his sixties. Also competing for the Palme D’Or is Italian maestro Nanni Moretti, 68 in August; the Hungarian auteur Ildiko Enyedi, 65; Catherine Corsini, likewise 65; Jacques Audiard, 69; Bruno Dumont, a mere 63, and Sean Penn, the Fast Times at Ridgemont High star who has now reached the grand old age of 60. Judging their efforts is a jury headed by Spike Lee, who is 64. Todd Haynes, who presents his documentary The Velvet Underground out of competition, is also in his sixties while Oliver Stone, premiering his new CIA-bashing, conspiracy theory documentary, JFK Revisited: Through the Looking Glass, is 74. In other words, the entire festival is like a tea party for the old folks.

When Portuguese master Manoel de Oliveira unveiled his quaintly titled feature Eccentricities of a Blonde Haired Girl at the Berlin Film Festival in 2009, he was over 100 years old but still delighted the critics with his impish humour and offbeat storytelling style.

As she grew older, the great French director Agnes Varda became almost as well known for her love of cats as for her love of cinema. Nonetheless, Varda’s autobiographical 2008 documentary The Beaches of Agnes, made as she hit 80, was one of her wittiest, most tender and remarkable films.

Jean-Luc Godard, one of the directors Tarantino most admires, certainly didn’t give up at 60. His provocative, playful essay films like Goodbye to Language (2014) and The Image Book (2018), made when he was well into his eighties, were still turning up in Cannes more than 60 years after the premiere of his legendary debut feature, Breathless (1960).

Festivals like Cannes and Venice are barometers for art house cinema but what about the box office? Do movies from older directors set the tills ringing? Do studios still need them, do they still feed them, when they’re 64? Cinema bosses around the world certainly hope so. They’re banking on James Cameron, now in his mid-sixties, to pull the business out of its post-Covid slump with his Avatar movies when they are finally released.

Look at the Box Office Mojo list of the top adjusted grossing movies of all time and you’ll find The Ten Commandments (1956) nestling in at number six. Its director Cecil B DeMille was in his mid-seventies when he made it but that didn’t affect his ability to part the Red Sea in the slightest. Hitchcock had turned 60 when he made Psycho (1960), one of his boldest, queasiest, most voyeuristic, violent and profitable films.

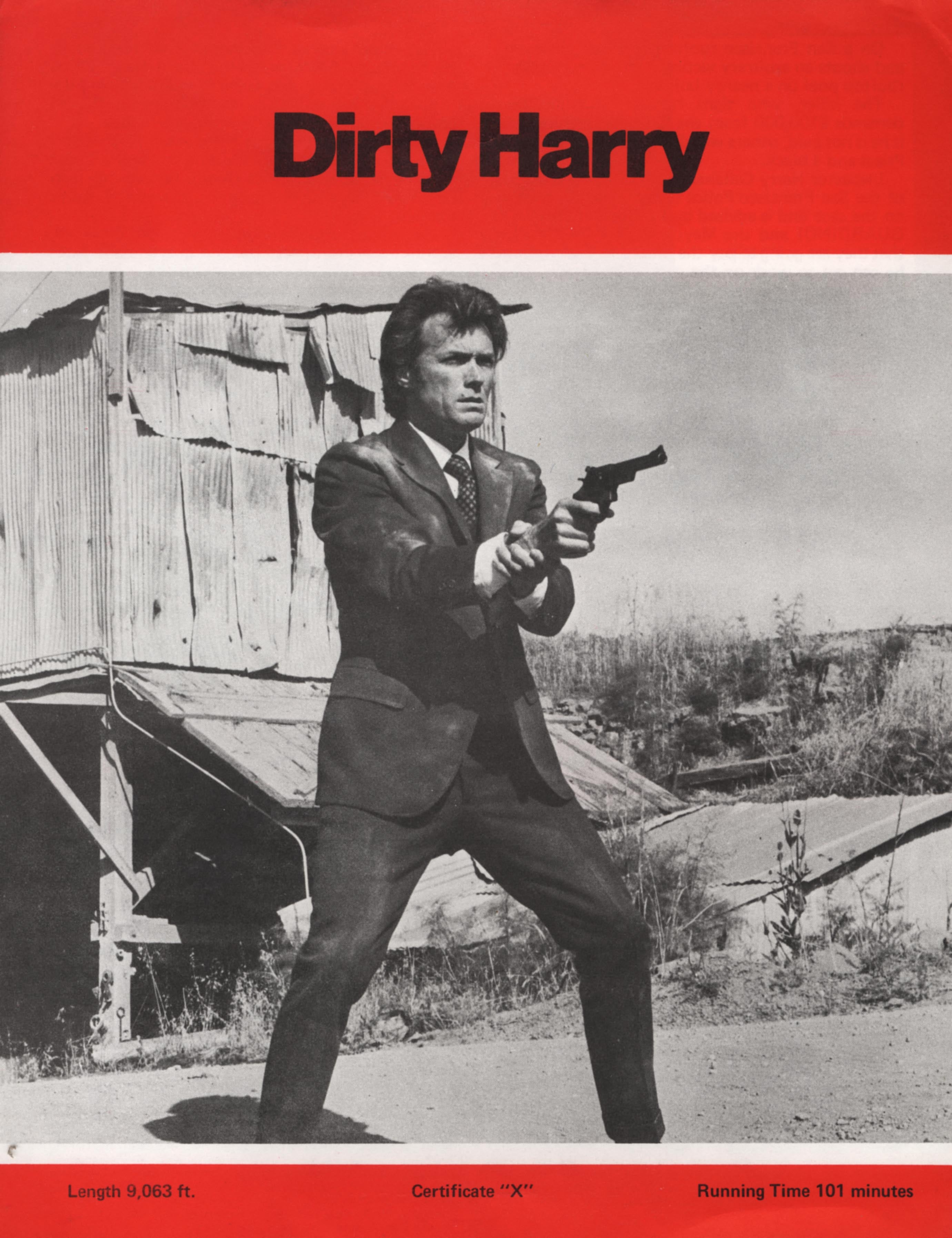

Tarantino cites Don Siegel as an example of a filmmaker who went on for far too long and tarnished his reputation but that comparison doesn’t really hold. Siegel, born in 1912, was already well into his sixties when he directed Clint Eastwood in Escape from Alcatraz (1979), a film Tarantino likes. He may have ended his career with misfires like Rough Cut and Jinxed! but if he had followed Tarantino’s example, he would have quit around Dirty Harry time (1971), thereby depriving audiences of the intriguing movies he went on to make later in the Seventies, among them Charley Varrick and The Shootist.

Received wisdom has it that filmmakers get worse, not better, over time. They pour all their creative ingenuity into their first few movies and then they’re either left with nothing new to say or no energy with which to say it.

Every generation has its share of once-acclaimed filmmakers who’ve grown older and lost their appeal. Backers won’t go near them. They end up on the margins of the industry and endure all the humiliations, small and large, that come with their diminishing status. Nonetheless, most try to keep on working as a matter of principle and professional pride.

One poignant example is the great English director Michael Powell in the years after he made his serial killer film Peeping Tom (1960), which the critics had reviled. It became harder and harder for Powell to get work in the UK. He turned instead to TV. He travelled to Australia to make a very strange and eccentric comedy, They’re a Weird Mob (1966), which Aussie audiences liked but everyone else ignored. Back in Britain, he directed a film for the Children’s Film Foundation, The Boy Who Turned Yellow (1972). These were very minor footnotes in his career compared to the great movies like The Red Shoes and A Matter of Life and Death that he and his collaborator Emerric Pressburger had made in the past. However, Powell refused to compromise or quit. “When everything I had created was collapsing around me, it never occurred to me that I was through,” he wrote in his autobiography. “Movies are my life. My life is movies. I am a director. I have always been a director.”

Retiring certainly wasn’t something that Billy Wilder contemplated either in the 1980s and 1990s when, daily, he’d go to his office on the studio lot and forlornly try to get another movie off the ground. He was a Hollywood legend who had fallen out of favour with the studio bosses. They wouldn’t give him the money to make his own films but would throw him the odd consultancy job instead. He was far too abrasive to be much good at that. “This picture is a big pile of shit. Perhaps I could tell you how to make it into a smaller pile but it will still be shit,” journalist Peter Bart remembers Wilder advising the United Artists (UA) bosses. Predictably, UA didn’t keep him on for long. Nonetheless, he didn’t consider giving up.

From Michael Haneke to Eric Rohmer, there are many examples of filmmakers who’ve made their richest, most resonant work in the latter part of their careers, at the very point where Tarantino would probably be calling for them to retire. Martin Scorsese and Paul Schrader may struggle to match the reckless adolescent intensity of earlier work like, say, Taxi Driver, but their films today still have an edge.

Tarantino should follow the examples set by Powell, Wilder and Scorsese. If the chance to carry on directing is there, he should surely take it. The worst that can happen is that his new films won’t be as good as those he made in his prime. He will still be admired for staying true to his vocation. He might even surprise himself by getting better with age. His decision to quit after only one more movie is the cinematic equivalent to holding up the white flag – a gesture of cowardice, defeatism and self-wrecking authorial vanity.

The Cannes Festival runs 6-17 July

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments