The Divine redemption of Hugh Grant: A look at 'the greatest PR save of all time' almost 20 years after he was arrested with a prostitute

When Benjamin Svetkey interviewed Hugh Grant 20 years ago, he had no idea that the actor would be arrested later that week – and that he’d still be writing Grant two decades on

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

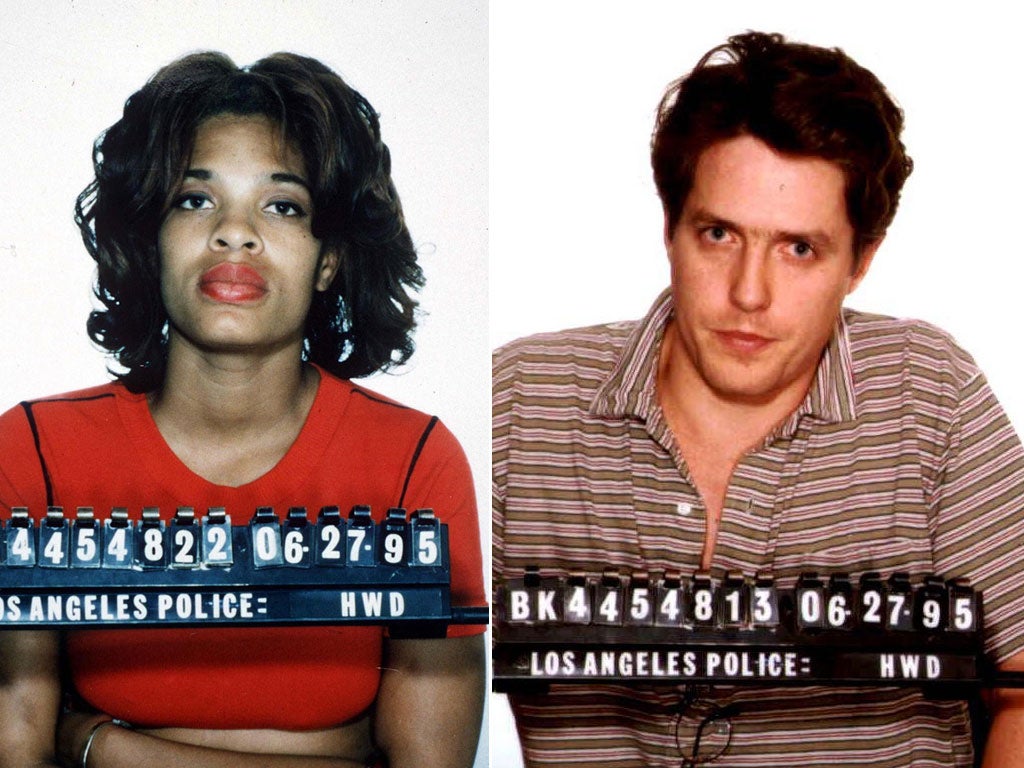

Your support makes all the difference.It has been nearly 20 years since Hugh Grant was arrested in Hollywood. His famous mug shot – the shrugged shoulders, the sheepish grin, the glasses tucked casually into the collar of his polo shirt – seems like a fading, distant memory. Today, most people might mistake Divine Brown for a flavour of Ben & Jerry’s ice cream.

But, for me, Grant’s bust was an unforgettable moment. You see, I was there on that summer day in 1995, witness to it all. Well, not all, but near enough. A few days before Los Angeles police arrested Grant off Sunset Boulevard with a hooker in his snow-white BMW convertible, I’d been a passenger in that car, in Divine Brown’s very seat, while Grant spent a lazy California afternoon driving me around Beverly Hills.

At the time, I was a young writer for Entertainment Weekly magazine. I’d been assigned a profile of Grant, who was in Los Angeles promoting his first big-budget American film, a hokey Chris Columbus parenthood romp called Nine Months with Julianne Moore. In those days, he was taking Hollywood by storm, thanks to his super-engaging turn in 1994’s Four Weddings and a Funeral, and my job was to give readers an close-up look at the Grant being heralded as the second coming of Cary. So I flew from New York to Hollywood to spend a couple of days interviewing him.

In a coincidence straight out of a hokey Chris Columbus comedy, I happened to check into the same Beverly Hills hotel where Grant was staying, and ended up in the room right next door to his suite. I discovered this first thing in the morning, when I opened my door and found the actor, in a hotel robe, collecting the wicker baskets of neatly wrapped overnight laundry in front of his entrance. “Don’t you just love the way they do the washing here,” he said, flashing that famous grin before ducking back inside.

When we met officially in the lobby a few hours later to start the interview, it took Grant a beat but he recognised me. “You’re in the room next to mine,” he said tentatively, shaking my hand slowly. “You can’t hear anything, can you?” I assured him I could not, which was true. Grant seemed relieved.

As was customary with celebrity profiles back in the Nineties, Grant and I had arranged an “activity” so that I’d have something more to write about than just the two of us chatting in a hotel room. Since Grant was being groomed as Hollywood’s newest leading man, I thought I’d show him around town. I picked up one of those cheesy Map of the Stars, and we set out in his BMW to find celebrity homes. As it turned out, the map was riddled with errors.

We saw a Japanese family leaving what was apparently Meg Ryan’s house. There was a parking lot where Pierce Brosnan was supposed to live. We could tell right away that we’d missed Madonna’s house by miles. “Does Madonna have a basketball hoop over her garage?” Grant asked rhetorically as we idled in front of who-knows-who’s driveway. “I think not.”

Interestingly, the one place Grant was genuinely keen on visiting – “the grail”, he called it – wasn’t on the map. He wanted to see the spot in Brentwood where, only a year earlier, Nicole Simpson had been slain. When we pulled up at the correct address, we were both surprised to see yellow police tape still blocking off the walkway to the house. “So, if I left my footprint on the other side of this tape, I’d be a suspect?” Grant pondered, dangling a trainer over the edge of the famous crime scene.

Being charming is part of a film star’s job description, but Grant gave it a bumbling, stumbling, floppy-haired spin that was irresistible. He was smart, funny, and endearingly self-deprecating (“I’d kill to shave my head – I’d love to do a Keanu Reeves”). Jolly English phrases – “easy peasy!” – sweetened his banter like verbal toffees. He didn’t reveal much about himself, but he was so entertaining that it didn’t matter.

“I frequently dream of having tea with the Queen,’’ he told me at one point during our car ride, apropos of nothing. “I dream about Lady Di, too – but that’s too kinky to get into here. I used to dream about Gorbachev before he lost power. I’d go into a panic because I was meeting him and I had nothing to wear. I’d ask my brother what to do, and he’d tell me to wear my dressing gown. I’d tell him I can’t – it’s too horrible. He’d tell me to wear his as well. So I’d meet Gorbachev wearing two dressing gowns. What would a psychologist make of that, do you suppose?”

It was impossible not to like the guy.

But then he got busted for picking up a hooker. I heard the news when my boss called me in New York the morning I got back from Los Angeles. As a journalist, I should have been thrilled. It was the sort of lucky break that reporters dream of. I found myself, in my own stumbling-bumbling way, at the centre of the biggest Hollywood prostitution story since, well, since Charlie Sheen’s name was leaked from Heidi Fleiss’s little black book the year before.

It’s hard to imagine now, in an era when celebrity sex tapes are practically live-streamed in real-time over the internet, but back then a film star getting caught with a hooker was a big deal. Newspapers and television networks on both sides of the Atlantic covered it as if it were the fall of the Berlin Wall. And I, as the last reporter to interview Grant before his big bust, was the closest thing there was to an eye- witness to history. “You’re the Bob Woodward of blow jobs!” one of my colleagues excitedly announced when I turned up at the magazine’s offices to write a very different sort of Hugh Grant story than I had intended.

Obviously, Grant had behaved reprehensibly. If I had been Liz Hurley, I’d have been furious. If I had been Chris Columbus, I’d have been furious. Grant had put his career and the careers of others in jeopardy for the dumbest of all possible reasons (“Well, at least it wasn’t an animal,” Columbus told me shortly after the arrest, looking on the bright side).

Still, I felt bad for Grant. I couldn’t help it – I liked the guy. And I pitied him for the media onslaught he was about to endure, and in which I was going to be a player. Even if his career survived –and at that point, I wasn’t at all convinced it would – I was sure he’d be living down the incident for the rest of his life.

Turned out, though, I was wrong. Grant went on his famous “apology tour”, begging forgiveness on late-night television. It ended up being one of the great PR saves of all time. I spoke to him on the phone a few hours before he made his career-rescuing mea culpa on The Tonight Show with Jay Leno. A follow-up phone conversation had always been a part of the arrangement for EW’s cover story, although I certainly wouldn’t have blamed Grant if he had reneged, given his situation.

But his publicity team must have calculated that it would do more good than harm to put him on the phone with me before he went on television, as a sort of warm-up act. “The suffering one goes through in these circumstances – you don’t mind it too much,” Grant said when I timidly asked how he was doing. “I almost feel as if I deserve a good whipping.”

A couple of hours later, he used nearly exactly the same words when talking to Jay Leno. In the end, Grant’s career was barely scuffed by the bust. Over the years since, he has appeared in a slew of decent movies (Notting Hill, Bridget Jones Diary, About a Boy, Love Actually) along with not-so-decent ones (Music and Lyrics, Did You Hear About the Morgans), always remaining very much a part of Hollywood’s A-list.

What seemed like such a huge, hair-on-fire deal at the time now barely rates a couple of hundred words in Grant’s Wikipedia entry, way down at the bottom of the scroll. Nobody cares about what he did in his white BMW in the summer of 1995. Indeed, today if the word scandal is used in the same sentence as Grant’s name, it’s more likely to be referring to the 2011 tabloid phone-hacking saga in which Grant was such a prominent victim (he’s been the public face of the Hacked Off campaign for media reform since 2011). In comparison with the privacy-invading crimes of Rupert Murdoch’s The News of the World, Grants’ run-in with the law looks like a parking ticket.

I haven’t talked to Grant since that last phone interview, but many years later he did speak to another EW writer, and confessed that he regretted making Nine Months. Not because of anything that happened on Sunset Boulevard, but because the studio that released the film was owned by Murdoch. “It would certainly stick in my craw to work for Fox,” he said. “I did make one film for them 16 years ago, but I was naive then. I didn’t even know who owned [the studio’].”

When pressed by EW’s sister magazine, People, on whether he feared being blacklisted by Fox because of his leading role in the Leveson Inquiry into the ethics of the British press, Grant was anything but fumbling or bumbling. “It couldn’t bother me less,” he said. “I don’t do much acting any more anyway, and not to work for 20th Century Fox is really the least of my worries.”

Grant was being modest about his acting. At 53, he’s still landing high-profile, if slightly greying parts, such as Leo G Caroll’s old role in Guy Ritchie’s upcoming Man from UNCLE adaptation. And he’s not the only one who ended up surviving the scandal without a scratch. Indeed, Divine Brown (also known as Estella Marie Thompson) became a millionaire with a mansion in Beverly Hills, thanks to media fees and endorsement deals tied to her dalliance with Grant. Elizabeth Hurley went on to become a film star in her own right (she and Grant broke up in 2000). Even Jay Leno came out ahead: Grant’s apology on his sofa sent The Tonight Show’s ratings into orbit, helping it beat Late Night with David Lettermen to become the No 1 talk show in America.

In fact, come to think of it, the only one who didn’t hit the jackpot since the arrest was me. Nearly 20 years later, here I am, still writing about Hugh Grant.

Benjamin Svetkey’s new novel ‘Leading Man’ (Phoenix, ebook £4.99, paperback £7.99) is available now