The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

Winter of 1989: The Velvet Revolution in pictures

35 years on, house librarian Tizane Navea-Rogers revisits the bloodless Velvet Revolution that changed the face of a nation

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.This week, 35 years ago, the Czech government buckled under the mounting pressure of its people. In mid-November, student protestors had ignited a revolutionary fervour on the cold streets of Prague that rapidly swelled into a nationwide movement. The president, Gustav Husak, resigned in December and appointed a new government led by non-Communists. After four long decades, Soviet-backed rule in Czechoslovakia was over.

Photographer Brian Harris was in Prague for The Independent, documenting the unfolding events on camera – the vast crowds surging through Wenceslas Square, the dramatic speeches, the student protesters and striking workers rallying support.

Revolution was already in the air that winter. Harris had just come from Berlin, where he photographed the dramatic fall of the Berlin Wall and the beginnings of a united Germany. Sensing “rumblings of discontent” to the south, he secured a visa and raced to Prague, arriving just in time to witness one of the first mass protests.

The atmosphere Harris encountered was “carnival like” and markedly peaceful. “There didn’t appear to be any threat or menace,” he later recalled. Wenceslas Square, the symbolic heart of Prague, witnessed thousands of demonstrators demanding reform, yet no blood was shed.

Edward Lucas, reporting on the ground for The Independent, described “the steady crumbling of the Communists’ hold” over the coming days. Action culminated in a two-hour general strike on 27 November and yet another mass protest in the “dank November chill”.

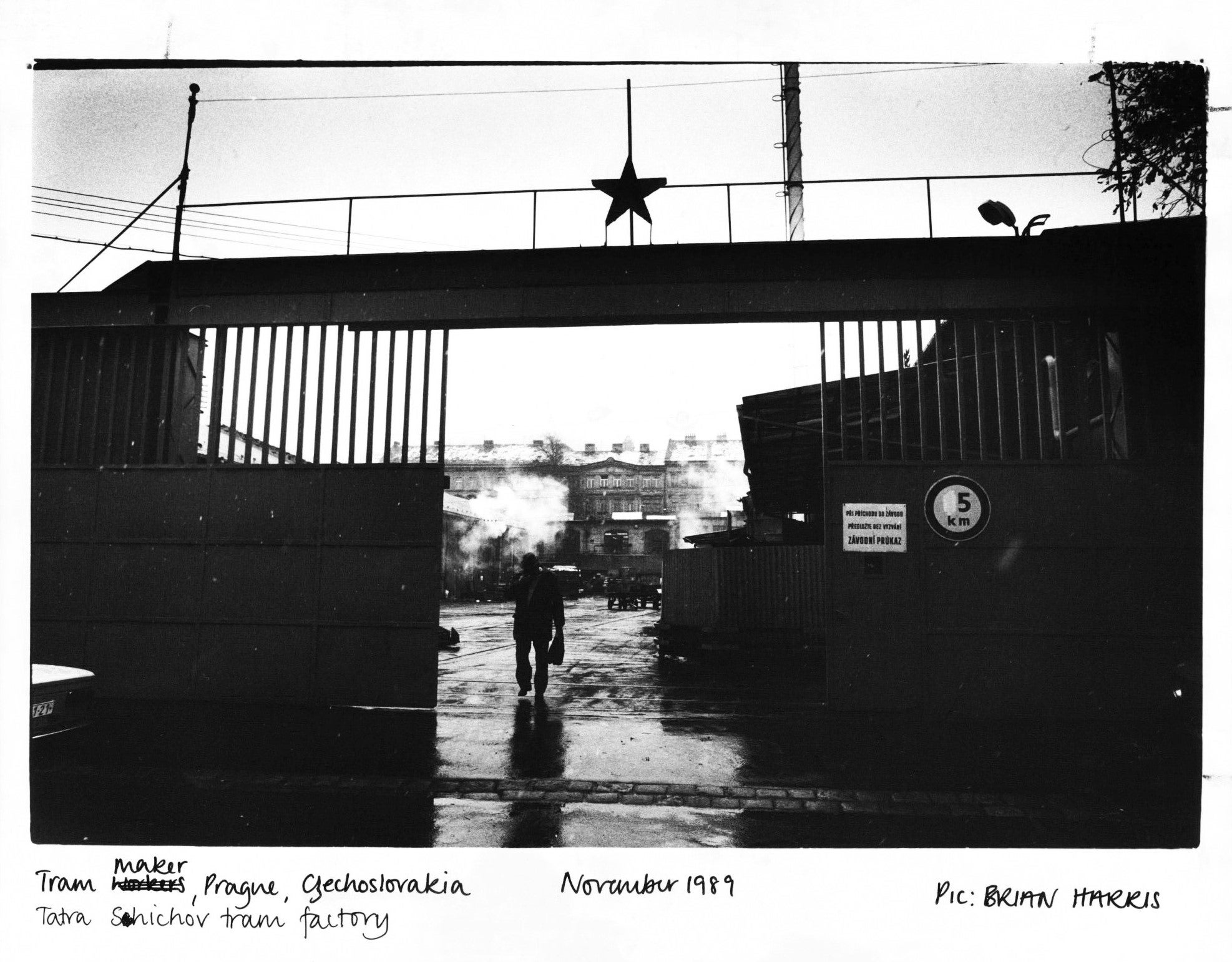

In one image taken by Harris, we see ribbons in the Czech colours (red, white and blue) being eagerly handed out to striking workers. Elsewhere, a worker is seen leaving a tram-making factory in Prague, a Communist star towering high above the gates. To Lucas, it felt as if the people of Czechoslovakia had been reawakened from a long two-decade “sleep”.

For those present, memories of the 1968 Prague Spring loomed large. The protests twenty years prior had been violently suppressed by Soviet tanks, leaving an estimated 108 Czechs and Slovaks dead and a puppet government in control.

Alexander Dubcek, the reformist leader of 1968, re-emerged from years of political obscurity in Slovakia and returned to Prague in November 1989. The crowds erupted in cheers when he appeared on a balcony above Wenceslas Square alongside dissident playwright Vaclav Havel. Here, Harris photographed keen supporters of the two men, motioning “V” signs from a nearby window.

While the nationwide movement was gaining momentum, many feared a violent crackdown. State media warned against the “anarchy” spread by “external and internal anti-socialist forces” and protesters were painfully aware that the regime could still flex its military grip. In one of his stirring speeches, Havel appealed to authorities to remember that the demonstrators were first and foremost “human beings and citizens of Czechoslovakia”.

On the streets of Prague, Brian Harris drew inspiration from the vivid imagery of Czech photographer Josef Koudelka in 1968. During the Prague Spring, officials had called a mass meeting urging people to show support for the regime. The public defied their government and refused to turn up. Koudelka shot the enduring image of an empty Wenceslas Square, his watch showing the mandated time when the square was supposed to be filled with “supporters” of the government. But instead, there was tumbleweeds and crickets.

Harris sought to juxtapose the empty Wenceslas Square of 1968 with a near-bursting one 20 years later. He later recounted: “My homage to Josef Koudelka and the people of Czechoslovakia was to replicate his image without the watch but with more than half a million of his fellow countrymen protesting as King Wenceslas looked out upon them as if he had come to life in their hour of need to raise his army of sleeping knights from the Blanik Hill.”

As the Czech regime finally fell after mounting unrest, Harris took his camera to the streets, capturing the celebratory scenes – from flags waving proudly from cars to quieter, more intimate scenes like a couple embracing in a secluded spot in Prague.

President Husak’s resignation eventually arrived in December and, weeks later, the playwright Vaclav Havel was elected president, ushering in a new chapter for the nation.

Harris’s imagery chronicles this seismic change driven by the collective will of ordinary people – workers, students, activists – all fighting for a future.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments