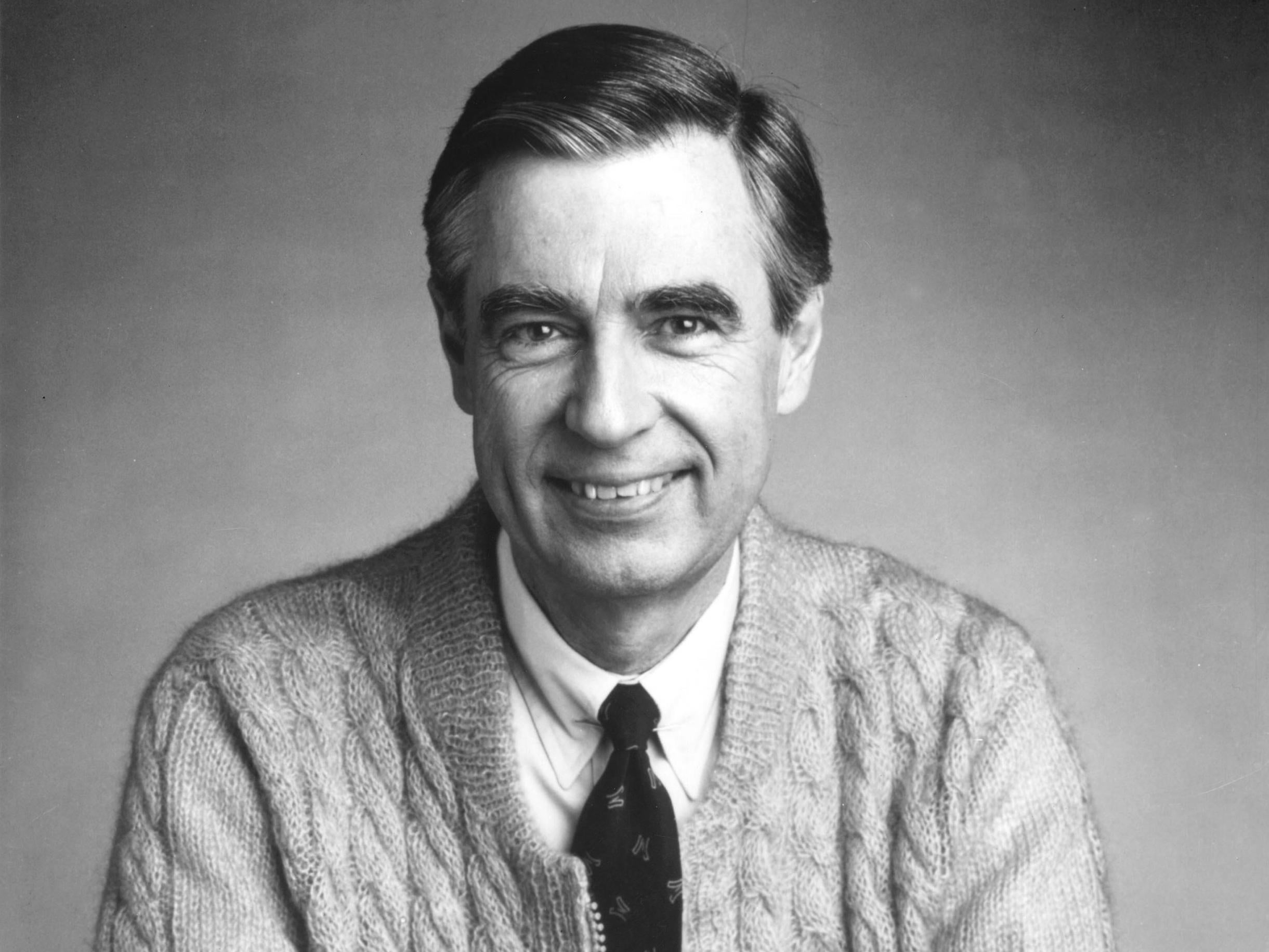

'Won't You Be My Neighbor?': How Mister Rogers used children's TV to tackle death, divorce and existential dread

Fifteen years after his death, Fred Rogers – the host of ‘Mister Rogers' Neighborhood’ and the subject of Morgan Neville's documentary – has found a new legion of fans, reports Alexandra Pollard

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.It’s 1968. Daniel Tiger – one of several puppet characters on children’s TV show Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood – is being shown how to blow up a balloon. “What if you blow all your air out?” he frets to Lady Aberlin, one of the neighbourhood’s human inhabitants. “But people aren’t like balloons, Daniel,” she replies. “When we blow air out, we get more back in.” She begins to blow it up again, breathing demonstrably as she goes. There’s a beat. “What does assassination mean?”

These are the kinds of topics – assumed by most people to be unspeakable to children – that Fred Rogers broached, again and again, on a TV show that valued honesty and compassion above all else. This particular episode, one of the earliest of the PBS show’s nearly 1,000-episode run, came after presidential candidate Bobby Kennedy was shot dead in a California hotel. News of his assassination and its grisly details were everywhere.

“I felt that I had to speak to the families of our country about grief,” said Rogers, an ordained minister who chose a more secular path when it came to offering emotional guidance to America’s children. “A plea not to leave the children isolated, and at the mercy of their own fantasies of loss and destruction.”

Though most of them were younger than 10, Rogers never condescended his viewers. “The adult instinct is to tell your kids not to worry about things,” 20 Feet from Stardom director Morgan Neville – whose new Fred Rogers documentary Won’t You Be My Neighbor? is out in select UK cinemas this week – told Deadline. “And what [Rogers] believes is children are way too smart to not know what’s going on. But if you can help them process things, those things won’t build up as fear, because he found fear to be the great toxic force in our universe. Because fear left untreated becomes hatred, resentment and bigotry.”

Fifteen years after his death, Fred Rogers is experiencing a resurgence in popularity – as people seek solace in his gentle, steadfast moral code. On YouTube, clips of Rogers’ show regularly amass millions of views, watched in large part by those who were either too young, or not alive, the first time around. Won’t You Be My Neighbor?, which explores Rogers’ life and legacy, has already become the highest-grossing biographical documentary of all time – it was released in the US in June, and has so far made $12.4m (£9.5m).

Next year, Tom Hanks will play Rogers in You Are My Friend, which is directed by Diary of a Teenage Girl’s Marielle Heller, and chronicles Rogers’ friendship with journalist Tom Junod.

Speaking of Rogers, Hanks said: “People would ask him questions like the great imponderables and the ironies of life, and one of the questions he was asked has always been, ‘What do we do in times of great struggle or great horror?’ And Mr Rogers said: ‘Look to the helpers. Yes, a horrible thing has happened, but you cannot give up hope, and if you need a source of hope, look to the helpers.’ It is possible to love thy neighbour with no exceptions. We can be good at that if we choose to be.”

Clearly, in a climate saturated by noise and anxiety – not to mention that toxic force, fear – Rogers is a tonic. Using his show’s puppet characters, or by speaking or singing directly to the camera, Rogers calmly guided his viewers through immensely complex issues such as divorce, death, anger, sadness – even existential crises. In one song, Rogers – singing as Daniel Tiger – admits, “Sometimes I wonder if I’m a mistake/ I’m not like anyone else I know/ When I’m asleep, or even awake/ Sometimes I get to dreaming that I’m just a fake.”

Nowadays, the closest we have to Mister Rogers is perhaps Blue Peter – but even that would never dare enter such difficult, melancholic territory. “If we, in public television, can only make it clear that feelings are mentionable, and manageable,” said Rogers in a 1969 address to congress, arguing to Senator John Pastore against Richard Nixon’s proposed $20m cut to funding of public television, “we would have done a great service for mental health.”

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

When he ended this address with a spoken rendition of “What Do You Do with the Mad that You Feel?”, a song about learning to acknowledge and control your anger, Rogers left the usually gruff Pastore teary-eyed. “I think that’s wonderful,” said Pastore. “I think it’s wonderful. Looks like you just earned the 20 million dollars.” On YouTube, the speech has been watched by 5.3 million people.

Politically, too, Rogers’ message was eerily prescient. In one early episode, uncovered in Neville’s film, imperious monarch King Friday XIII decided to build a wall around the neighbourhood, establishing a border guard. “King against change,” read the newspaper headlines – before balloons adorned with messages like “peaceful coexistence” prompted a change of heart.

As society becomes increasingly fearful and inward-looking – the result of which is the likes of Donald Trump and Brexit – Rogers’ words are needed more than ever. “We live in a world in which we need to share responsibility,” he once said. “It’s easy to say, ‘It’s not my child, not my community, not my world, not my problem.’ Then there are those who see the need and respond. I consider those people my heroes.”

“I can’t think how he would feel about the things that have set us back so far,” says Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood producer Margy Whitmer in Won’t You Be My Neighbor?. “I wonder if he wouldn’t have set down his tiger, and just stayed home.”

But according to Junlei Li, the co-director of children’s education group The Fred Rogers Centre, that’s not what we should be considering. “It’s not a question that you can answer,” he says. “The most important question, is what are you going to do?”

Won’t You Be My Neighbor? arrives in UK cinemas on Friday 9 November

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments