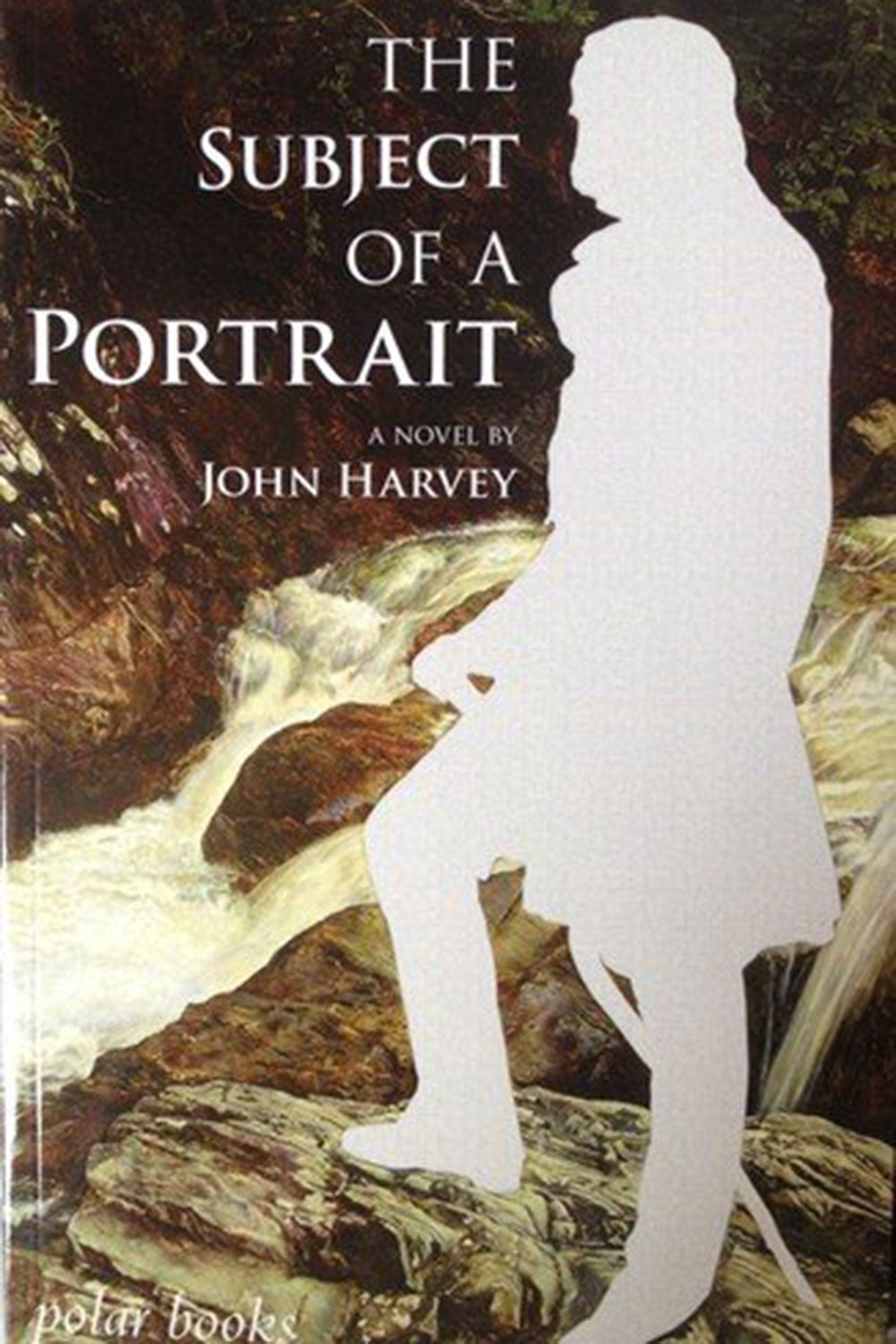

The Subject of a Portrait by John Harvey, book review: A discerning and sumptuous study

Captivating story of a love triangle peopled with sympathetic characters

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.John Ruskin, Victorian Britain’s pre-eminent art critic, could make or break the reputations of academicians. His protégé was John Everett Millais, the celebrated Pre-Raphaelite artist and one of the founding members of the Brotherhood. In the summer of 1853 the two men travelled to Scotland with the purpose that Millais would paint Ruskin’s defining portrait.

Accompanying them was Millais’s brother William, and Ruskin’s wife of five years, Euphemia (Effie). By the time the party returned to London, Millais and Effie had fallen in love, and, in a scandal that rocked both the art world and polite society, the Ruskins’ marriage was annulled on the grounds that it had never been consummated, after which Effie and Millais became man and wife.

The details of precisely what happened in the Scottish Highlands have been the topic of much speculation over the years, resulting in a flurry of dramatisations (the most recent of which is the film Effie Gray), as those captivated by the story have attempted to fill this void.

John Harvey uses this metaphor to great effect in his new novel, The Subject of a Portrait. Although Harvey tells the story from the perspectives of all three involved – as based on Millais’ work from the period, and what details of the affair have made the historical record – it’s the figure of Ruskin around whom the book is focused. After Millais chooses the background against which he intends to paint his subject, he begins with the details of the setting, leaving the man a mere “outline”, a blank “shape” to be filled in at a later date. The novel works in a similar fashion: Ruskin’s silhouette is slowly filled in with every turn of the page.

The portrait Harvey paints of the great critic is gloriously riddled with the contradictions that make him so intriguing a subject. On the one hand, there’s his strange upbringing, “patted and petted and coddled and cooed over” by his doting mother, kept as a child long out of infancy, the consequences of which are his lifelong attraction to childish innocence and his tendency to retreat into baby talk. But on the other there’s the respected public figure who wields his patronage with a fist of iron, believing Millais’ art is his alone “to command”.

It’s a rare feat to be able to turn such familiar fodder into so captivating a story peopled with such sympathetic characters. Harvey’s novel might not break new ground, but it’s a discerning and rather sumptuous study of one of history’s most infamous love triangles.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments