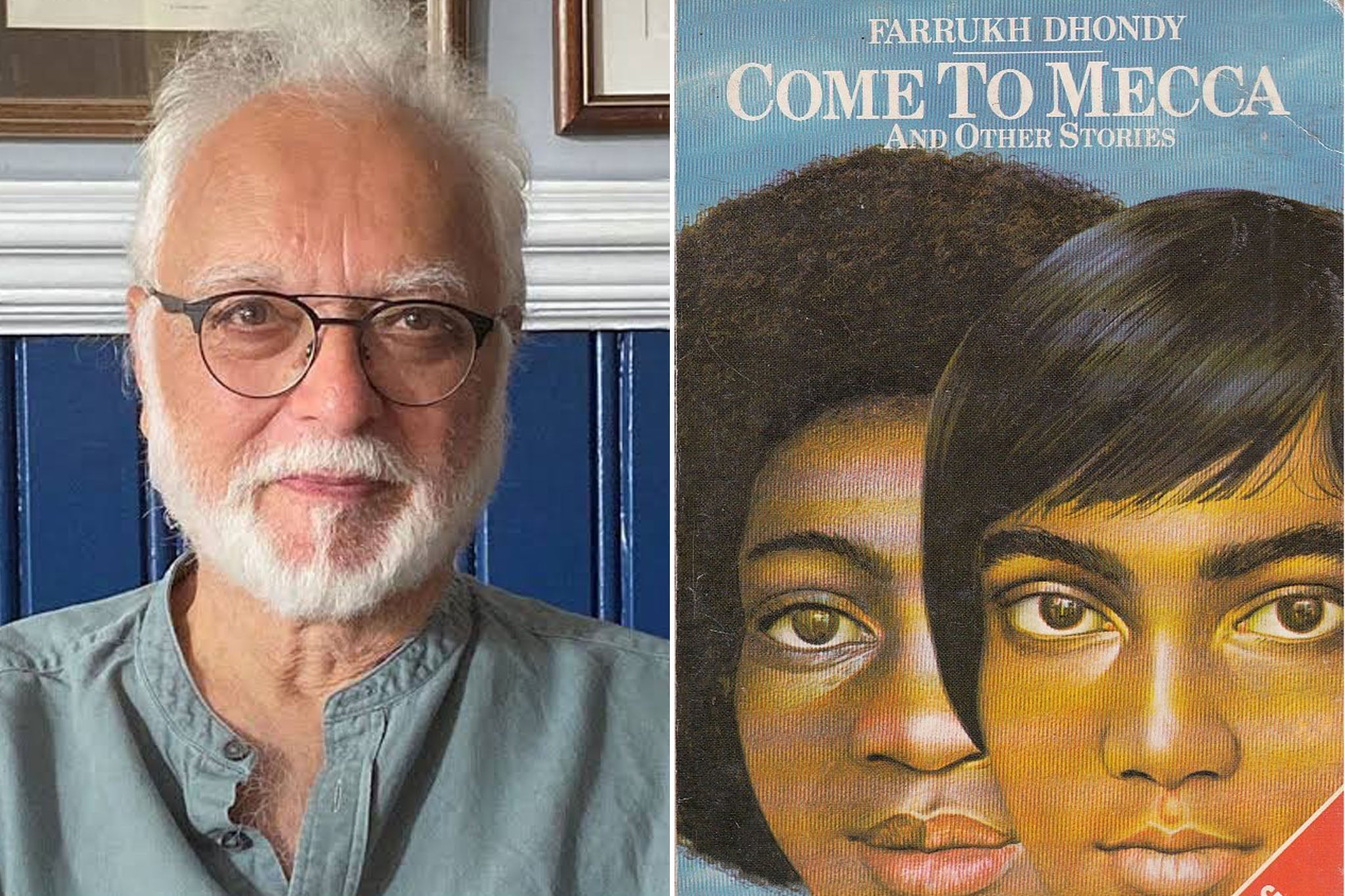

Book of a lifetime: Come to Mecca by Farrukh Dhondy

Natasha Soobramanien reminisces on the short stories that opened her eyes to racial identity and inspired her to become a novelist

The population of Norwich in the early Eighties was not ethnically diverse. So when my family – Mauritian in origin – moved to the city, to what was then a white working-class area, we were objects of some suspicion. Perhaps a kinder word would have been “curiosity”. Certainly, it never got worse than name-calling – the ubiquitous “Paki” shouted across the street. This didn’t bother me.

I was a 10-year-old snob who read too much and craved friendship only with rich girls or those from intellectual, bohemian families. My parents, worried about racially motivated bullying, scraped together the cash to send me to a fee-paying school. If I was exotic to the girls at this school, then so too were they to me. The two who would become my best friends were from the kinds of families I longed to infiltrate – Rachel’s was eccentric and feral in the way of impoverished, titled families, while Annabel’s was solidly bourgeois, a species of rural Sloane. What affirmed their exclusiveness was their hair – both girls were dazzlingly blonde.

At the age of 10, the extent of my racial awareness lay solely in physical differences. That all changed the day I came across, in the classroom, a copy of Farrukh Dhondy’s Come to Mecca. This collection of short stories for young adults published in 1978 was by a writer of Indian origin who taught in an inner-London comprehensive. Dhondy had drawn on his experience of immigrant communities for his savagely comic and angry stories of young first- and second-generation Britons exploring their conflicted sense of racial identity. It blew my mind.

The stories showed me there were many ways to be brown or Black or otherwise “other”; that this otherness went beyond skin colour and had more to do with what language you spoke at home, what food you ate, where your parents had come from. In other words, your story. But if there were many stories about this – where was mine? Soon after asking myself this question, I began – at home, and for myself – to write.

Years later, when I came back to Norwich to study creative writing, I met the man who had originally commissioned Dhondy’s first collection, East End at Your Feet. I learnt that the book’s acknowledgement of sexual relations between Black and white teenagers so horrified the National Front and The Daily Telegraph that both had run a campaign against it. I hope Come to Mecca continues to be read today in schools of all kinds and – where they still exist – libraries.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments