Barbara Hepworth: a brief look into the artist's life as three shows open at The Hepworth Wakefield

Wakefield has stolen a march on Tate Britain’s upcoming Barbara Hepworth retrospective with three shows showing her to be more daring than her male peers

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

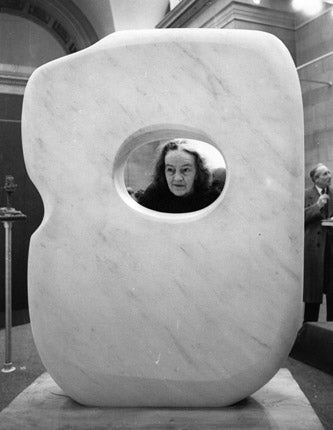

Your support makes all the difference.This could be called the summer of Barbara Hepworth but the question one needs to ask is whether she is worthy of all the attention. Recently a fellow critic dismissed her as merely provincial. The Hepworth Wakefield pre-empts the upcoming Tate Britain’s retrospective with three shows – Hepworth in Yorkshire, A Greater Freedom: Hepworth 1965-75 and Plasters: Casts and Copies – placed alongside its holdings of the Hepworth Family Gift.

Regarding works from the last decade of Hepworth’s life, this tightly curated show focuses on a period where Hepworth was experimenting with new materials. This was a prolific period for Hepworth; largely released from the duties of a young family, she made nearly as many works in the 1960s as she did in the period between 1925 and 1960, according to Alan Bowness (the director of the Tate from 1980–1988 and also her son-in-law).

Here elegant large screen prints in delicate colours surround the sculptural works, some in marble others in bronze. These were materials now financially available to the artist after her recognition from representing Great Britain at the Venice Biennale of 1950, winning the Grand Prix at the Sao Paolo Biennale of 1959, and a commission to create the large Single Form for the United Nations in New York in the early 1960s. Marble clearly was a material that she enjoyed exploring later in life, and carving was a skill that she had learnt in Italy years before.

Hepworth in Yorkshire chronicles Hepworth’s early years growing up in Wakefield; she was born there in 1903. Her father was an engineer and became county surveyor. The young artist often travelled with him around the county, and claimed that the landscape deeply influenced her work. She attended Leeds School of Art with Henry Moore as a fellow student before moving to the Royal College of Art, where he again was a fellow student. There are photographs of a stylish young woman about to travel to Europe, where she married fellow artist John Skeaping, who had won the Prix de Sculpture at the British Academy in Rome (she was a runner-up).

The star of this small show is an early plaster relief, Jill and Peggy (1918), that she made of her cousins. Hepworth’s uncle was a GP and provided her with plaster that he used as casts for broken bones, a material in a different form that she continued to use with great panache through her career.

Hepworth returned from Europe a married woman but met the artist Ben Nicholson while on holiday in Norfolk. She soon divorced Skeaping and lived and worked with Nicholson in Hampstead in London. In 1935 Piet Mondrian arrived in London and the couple helped him to find accommodation near them. Nicholson and Hepworth travelled extensively and in 1935 met both Brancusi and Arp at their studios. In 1940 Hepworth married Nicholson after his divorce from his first wife was finalised. In 1949 she bought Trewyn Studio in St Ives, where she lived permanently until her death in 1975.

In 1965 Hepworth had her first exhibition at the Tate Gallery in London, a show that was largely self-curated, and which was met with mixed reviews. By 1968 her retrospective exhibition opened in the Rietveld Pavilion at the Kröller-Müller Museum in the Netherlands. She was made a Dame and appointed a Trustee of the Tate Gallery (until 1972), its first female trustee.

This biography is important in the light of all the shows that are now obviously trying to reposition Hepworth into a more international perspective. Dismissing her as merely provincial is obviously wrong. In this period both pre- and post-Second World War there was continental migration that makes a global reading much closer to the mark. It is clear looking at Hepworth’s work that Arp, Brancusi and in particular Naum Gabo, the Russian Constructivist artist who worked with them both in London and St Ives, all had an influence.

Here in Hepworth’s carved marble forms of a work such as Child and Mother (1972) one can see the sinuous shapes of Arp, and in Idol (1971), a polished bronze, an appreciation of Brancusi’s work Flight is apparent. Gabo’s often stringed tension is also to be found in the study of Winged Figure. But it would be reductionist to think that Hepworth is merely a magpie of others’ techniques.

What is beautifully apparent here in these shows, seen alongside the rich Hepworth Family Gift, is that this was a woman who was not afraid to experiment, given the means, time and space to do so. There are large muscular plasters that she vigorously carved into near the smaller more polished marble works. There are glorious accents of colour that might well be called daring if performed by a male artist’s hands.

In Plasters: Casts and Copies, contemporary artists working in the material powerfully carry on the tradition. A serried row of heads by Thomas Schutte impress and Daniel Silver’s mash-up works of classicism and modernism stand their own. Rebecca Warren has never looked so right with her two clumsy-appearing crude figures and a small colourful work, The Clown by Kurt Schwitters, is worth the trip to Wakefield alone.

There are also some questionable choices. Placing the later, obviously carefully selected, Hepworth works on what seem anachronistic plinths of breeze-blocks you could be excused for confusion. Having listened to Tate Britain director Penelope Curtis’s lecture before the opening I realise this is an attempt to recreate the show at the Rietveld Pavilion, where the works were placed on this material in an attempt to make them seem “modern”. It’s a choice that might well have seemed correct then but, with the advent of sculptors such as Anthony Caro taking the work off the plinth, now seems a strangely unsuccessful solution, and out of the context of the architectural Rietveld pavilion it just seems wrong.

While the Tate show of Hepworth was met with critical indifference, Henry Moore’s retrospective at the Tate of 1968, curated by the late great curator David Sylvester, was largely acknowledged as being the moment that confirmed him among the top international sculptors of his time.

Sylvester was a good friend and he would often play a game with me. Naming an artist, Hepworth for example, he would say: “Major-minor, major-major or minor-minor?” This is a good moment to consider Hepworth in the light of Sylvester’s show of Moore. The answer to me is major-major.

It would be so easy for a woman working in such a rich artistic mixture of the time to be totally eclipsed by her artistic peers. There is an undoubted feminine elegance in the work, but there is also a rigour, a knowledge of the surroundings that is exciting to see, mixed with a recognisable sculptural language. One would never mistake her powerful, muscular, often totem-like geometric forms for those of Moore but their perforations allow another view for the spectator that I personally can attest to. As a mother raising young children on a street with a Hepworth – outside Churchill College in Cambridge – I would visit them with children in pram or pushchair every day to say peekaboo – a game that they and I would never tire of.

Hepworth in Yorkshire until September 2015; A Greater Freedom: Hepworth 1965-75 and Plasters: Casts and Copies until April 2016 at Hepworth Wakefield

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments