Labour is resurgent – and prepared for power

Editorial: New Labour took most of a decade to rebuild the browbeaten party. With these election results, Keir Starmer has shown, with his steady and ruthless determination to become electable again, he has done the same within a single parliamentary term

So acclimatised is the nation to Labour’s electoral dominance that it takes some effort to recall a time when the party seemed doomed to be in the wilderness for a generation. It is not so distant.

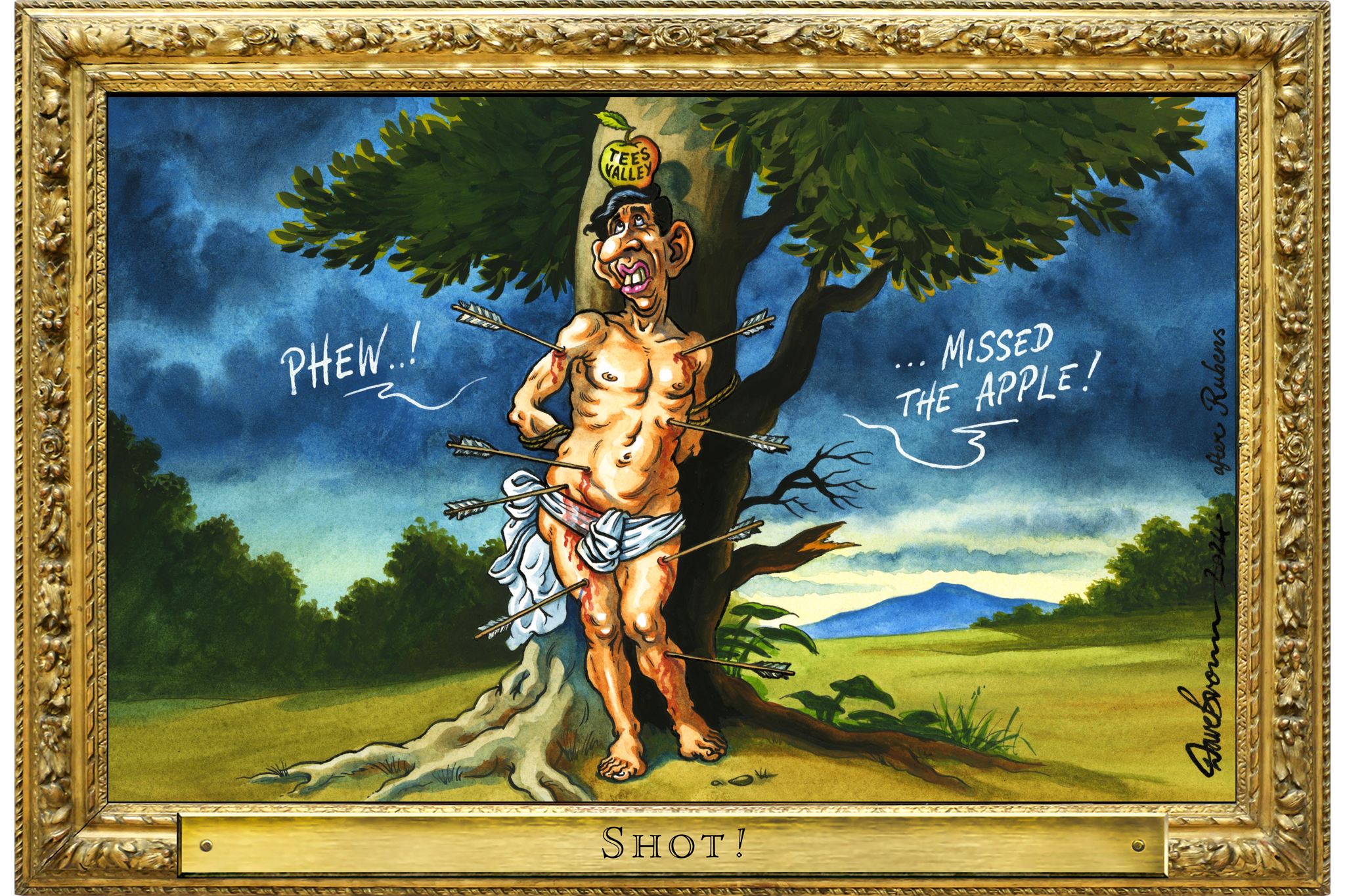

Only three years ago, almost to the day – Thursday 6 May 2021 – the Conservatives took the Labour heartland seat of a Hartlepool on a 16 per cent swing. It was highly unusual for an opposition party to lose a safe seat to the governing party, and it was such a dispiriting outcome for Sir Keir Starmer, then fairly new to the role of Labour leader, that he thought about quitting.

It was just as well for him that he persevered. Now, his party has regained control of Hartlepool Council, and enjoyed almost unalloyed success across the land. The Labour win at the Blackpool South by-election came with a 26 per cent swing, which is just as “seismic”, as Sir Keir says, as the other ones over the past year.

In parliamentary terms, all the indications are that Sir Keir’s “changed Labour Party” will surpass the landslide victories won by Tony Blair in 1997 and 2001. Whereas New Labour took most of a decade to rebuild the organisation, the present leader has done so within the span of a parliamentary term.

It is not exactly a miracle; but it was certainly improbable and, to a large degree, the product of Sir Keir’s steady and ruthless determination to make his party electable again. He had, as the cliche goes, a mountain to climb. The party’s showing under Jeremy Corbyn at the 2019 general election was the worst since before the Second World War. There was much talk about a historic realignment of domestic politics as a result of Brexit, and Boris Johnson was supposedly making plans to take his administration, widely assumed to be invincible, into the 2030s.

Now, thanks in no small part to the Labour leader’s relentless pursuit of him, Mr Johnson is no longer even an MP, and the coalition of red wall and blue wall voters he assembled for the “get Brexit done” election has been unravelled by Labour. The Brexit effect which propelled Mr Johnson to power and secured his historic victories has been reversed: in these elections, Labour has made its most spectacular progress in areas which registered the highest Leave support in the 2016 referendum. From Scotland to Essex, and from Hampshire to Mr Sunak’s backyard in North Yorkshire, Labour is resurgent.

Of course, Sir Keir has been fortunate in his opponents. Mr Johnson’s behaviour during Partygate, and subsequently being found to have lied to the House of Commons, didn’t help his chances of survival, even had Sir Keir not been so diligent about exposing him. The contribution of Liz Truss to the success of the Labour Party remains historic; and Rishi Sunak, as one Conservative commentator puts it, is a nice and decent man who, it turns out, isn’t all that good at politics.

Even now, Mr Sunak seems incapable of giving his party something compelling to sell on the doorstep, and is fixated on his Rwanda plan – to zero electoral advantage. The Conservatives may plead that the pandemic, and then the energy crisis, destabilised everything; but their job was to manage these vicissitudes better than they did.

The scale of the Labour leader’s electoral achievements cannot be disputed, even discounting some leakage to the Greens and ex-Labour independents over policy towards the war in Gaza. He has cleansed much of his party of its endemic antisemitism, marginalised Mr Corbyn and his allies, formed a solid and cohesive team, and dragged policy towards the centre ground. He and his formidable shadow chancellor, Rachel Reeves, are taking the challenges of governing ahead of them seriously, and are right to keep their ambitions and their language realistic.

The voters have had quite enough of impossible promises and “cakeism”. Though many would yearn for a much more enthusiastic attitude towards revising or even reversing Brexit, sadly the country is in no state to withstand another civil war about Europe.

Sir Keir Starmer is in as strong a position as any leader of the opposition preparing for power. It was never inevitable that the national mood for change would manifest itself in such a strong showing for Labour rather than, say, one of the smaller opposition groups, though the Tory defections to Reform UK have added momentum to the Labour effort and scale to its future Commons majority.

In any case, Sir Keir is entitled to taste success and celebrate his landmark victories. It is difficult to see who else in the Labour Party could have replicated what he has accomplished – but he also understands better than most that the hard work is only just beginning.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments