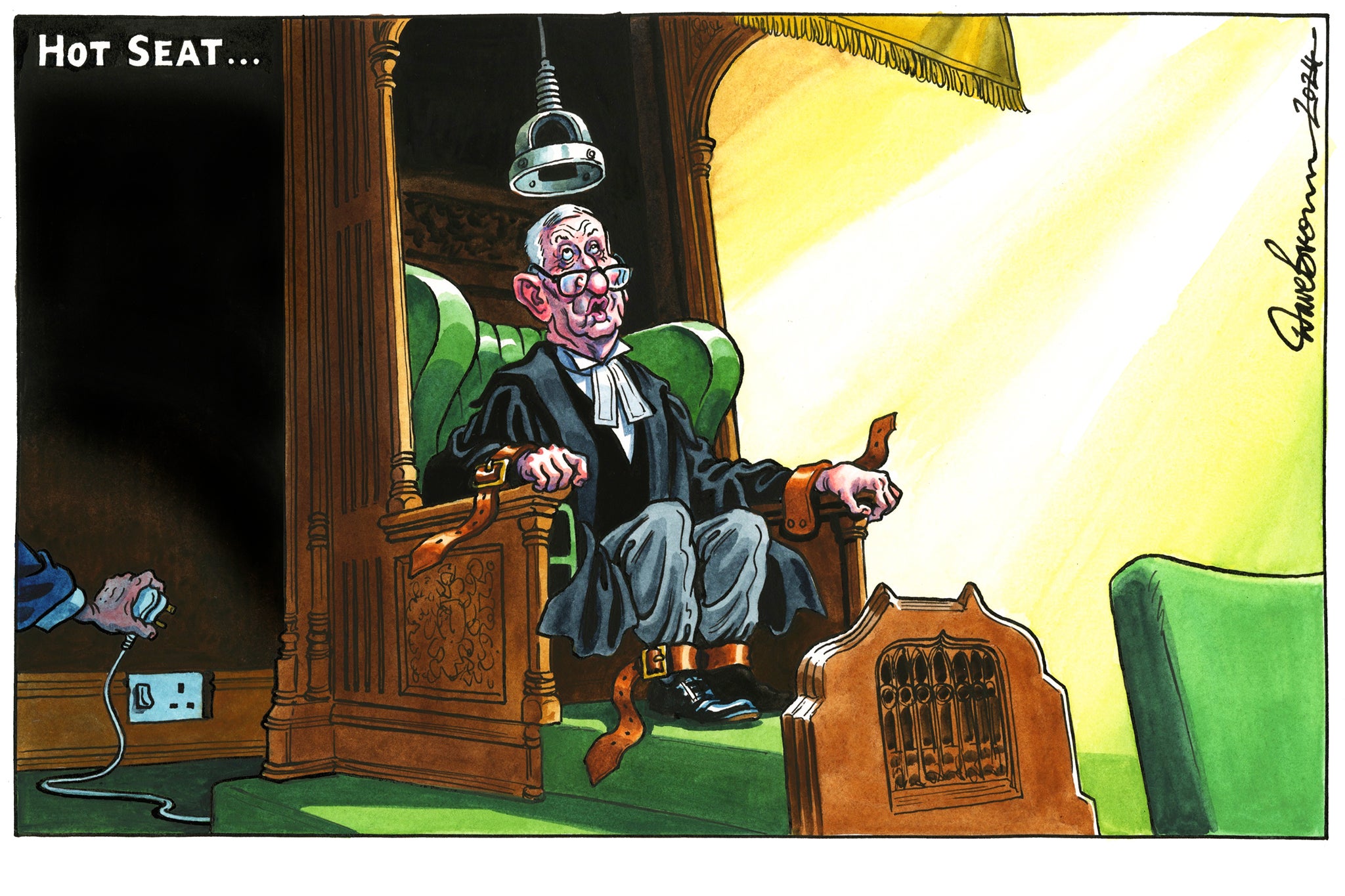

The Lindsay Hoyle fiasco highlights the need for reform in the House of Commons

Editorial: Not since Brexit has it been so clear that the traditional procedures of the House are inadequate when it comes to resolving certain issues

If the Wednesday night fiasco in parliament was a shameful sight, then the Thursday hangover has been scarcely more edifying. The public, with better things to do than study Erskine May and weigh the merits of standing order 31 of the House of Commons, have witnessed how what was supposed to be a debate on the situation in Gaza – which people do care about – plunge into a procedural quagmire.

By accident, a Labour Party amendment on Gaza – that probably shouldn’t have been accepted, let alone proposed for a vote, and would never ordinarily have been passed – became the formally adopted and unanimous view of the British House of Commons on the Middle East conflict. Absurd. This was not our parliamentarians’ finest hour.

The descent of what ought to have been a serious but low-key debate on an SNP motion, with appropriate time given to a minority party, was a disgrace. It was in fact painfully reminiscent of the worst days of the parliamentary Brexit permacrisis before the 2019 general election. As Geoffrey Cox MP, then attorney general, told the chamber at that time of chaos, any voter observing their proceedings would protest in dismay or despair: “What are you playing at? What are you doing? You are not children in the playground, you are legislators.”

As it happens, it was not legislation that was before the House, but the point remains. Members of parliament as a cadre did not do what their constituents expect them to do – or, at least, would like to be able to expect them to do. The UK may or may not have as much influence in the Middle East as it would wish, but matters of life and death were being discussed, and it looked very much like that context was not being treated with proper respect.

It is regrettable that the aftermath of the chaos has become a blamefest. The SNP blame the speaker for them being deprived of their parliamentary rights.

The Conservatives blame Labour, and Sir Keir Starmer personally, for bullying the Commons speaker and placing him in an invidious position. Labour blames the SNP for making political mischief and blames the Conservatives for removing themselves from proceedings and thus wrecking Sir Lindsay Hoyle’s plan to allow the views of three parties to be discussed in sequence.

The Liberal Democrats wonder why, if one opposition party (Labour) is allowed to try to amend the motion of another opposition party (SNP), they were prevented from doing the same. Plaid Cymru ask if smaller parties have any rights left, if their business can be hijacked by Labour when it suits Labour.

Extraordinarily, the clerk of the Commons published a letter to the speaker warning him about the risks he was running by trying to take a novel path. Sir Lindsay pressed on, but his plan collapsed.

Sir Lindsay made a mistake – and, as it turns out a grievous one. It was motivated by good and less good instincts. The leader of the opposition lobbied him, with all his usual persuasiveness, to allow Labour to put its own policy forward for debate. That was against the rules and most precedent; but on such an emotive issue there was a case, in the spirit of fairness to all parties that the speaker embodied, to allow that on this occasion.

Sir Lindsay also admitted that the safety of MPs was a factor in his calculations; if Labour MPs were forced into a position where enemies could claim they refused to vote for a ceasefire, then for some that could lead to the threat of violence – or worse.

An emotional man, still haunted by the assassinations of David Amess and Jo Cox, Sir Lindsay was swayed. It was an error of judgement. The safety of MPs is a matter for the speaker, but he cannot do everything. That is principally for the police and the security services, as he well understands. He left himself looking as if he was doing Labour a favour, even if he was not.

It has damaged his reputation, and he has to regain the confidence of the House. It is hardly ideal that a significant number of MPs have been calling for him to quit, and for the leader of the third-largest party in the Commons, Stephen Flynn of the SNP, to express no confidence. But it seems that his previously fine record, his sincere apology and his offer to run the Gaza debate again, will be sufficient for him to stay in post – and the Conservatives, taking their cue from the leader of the House, Penny Mordaunt, seem now to be switching their ire from him to the leader of the opposition.

It would certainly be undesirable for the House to eject its third speaker in a row. Sir Lindsay has not behaved anywhere near as extraordinarily as his immediate predecessors, John Bercow and Michael Martin. He will survive.

What became clear during the Brexit debates, and has become apparent again, is that some of the Commons’ traditional procedures involving motions and successive amendments aren’t necessarily well-suited to resolving some issues.

New techniques could be experimented with, as they were a few years ago, such as the “indicative votes” on Brexit options (albeit where all three were rejected by the House). Parliament is full of scholars and experts and has cross-party procedure committees that could suggest better ways of doing business.

It is telling, and a little ironic, that the process of motions and amendments that had been traditionally used to select a new speaker was abandoned a few years ago when it became impractical, in favour of a more straightforward ballot.

Having been through the fire, Sir Lindsay should make sure that modernised, innovative and reformed procedures will help parliament avoid too many more repetitions of the recent shenanigans. It’s not what the public, as taxpayers, are paying for.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments