Stargazing in May: V is for Virgo

Surveys with large telescopes reveal at least 2,000 galaxies in the Virgo cluster, along with an immense amount of dark matter whose gravity glues the cluster together, writes Nigel Henbest

The ancient Romans celebrated this time of year with the Floralia, a weeklong festival in honour of Flora, the goddess of springtime, flowers and fertility. We still have an echo of these rites of spring in our May Day traditions, with its pagan maypole andthe May Queen, dressed in white and decorated with blossom.

And the sky has its own May Queen this month, in the shape of the constellation Virgo. In ancient Babylon, this star pattern was identified as a furrow in a field, symbolising a fruitful harvest. The Greeks, on the other hand, saw these stars as their goddess of justice, Astraea, who was wise and virtuous. She lived on Earth during the Golden Age of the world, but as humans became greedy and deceitful she ascended to the heavens. Her scales of justice lie at her feet, as the constellation Libra.

Virgo is the second largest constellation in the sky, after neighbouring Hydra (the Water Snake). Its chief glory is the bright star Spica, whose name – meaning ‘ear of corn’ – harks back to the Babylonian tradition.

Spica is the 16th brightest star in the night sky. It’s a hot, blue-white star over 20,000 times brighter than the Sun, boasting a temperature of 25,000°C. Spica has a companion, which circles it more closely than Mercury orbits the Sun. Even the most powerful backyard telescope won’t show these stars separately, but an analysis of Spica’s light shows that the close companions inflict a mighty gravitational toll on each other, stretching each star out into an egg shape.

The other major stars of Virgo form a Y-shape, reaching upwards from Spica towards Leo (the Lion). The star at the junction of the Y is named Porrima, after a Roman goddess of prophecy. Grab a telescope, and you’ll see Porrima is a glorious double star: a pair of pure white stars, each a little brighter and hotter than the Sun, orbiting one another every 169 years.

At the top-left of the Y is Vindemiatrix – ‘the grape-harvester’ – a star about the same temperature as our Sun but 80 times brighter and 12 times wider. Scan the region to the right of Vindemiatrix with a telescope on a dark night, and you’ll find dozens of fuzzy blobs: the brightest members of the Virgo cluster. Each of these galaxies is more luminous than our Milky Way, but they are seriously dimmed by their immense distance of 54 million light years from us.

Surveys with large telescopes reveal at least 2,000 galaxies in the Virgo cluster, along with an immense amount of dark matter whose gravity glues the cluster together. Its gravitational pull is so intense that the Virgo cluster even affects the motion of the Milky Way through space.

The undoubted queen of the Virgo cluster is a galaxy catalogued as M87. It boasts a central black hole over six billion times heavier than the Sun – the first black hole to be imaged, in 2019.

A couple of other “firsts” for Virgo, though not objects you can easily see for yourself. The first quasar, 3C 273, was discovered in Virgo in 1963. Astronomers now know that this puzzling source of intense radiation is an incandescent disc of gas swirling around a massive black hole.

And in 1992, radio astronomers discovered the first known planets outside the Solar System in Virgo. Surprisingly, they don’t orbit an ordinary star, but are circling the remains of a star that has died – a collapsed neutron star (or pulsar) – now known as Lich after an old English word for corpse.

What’s Up

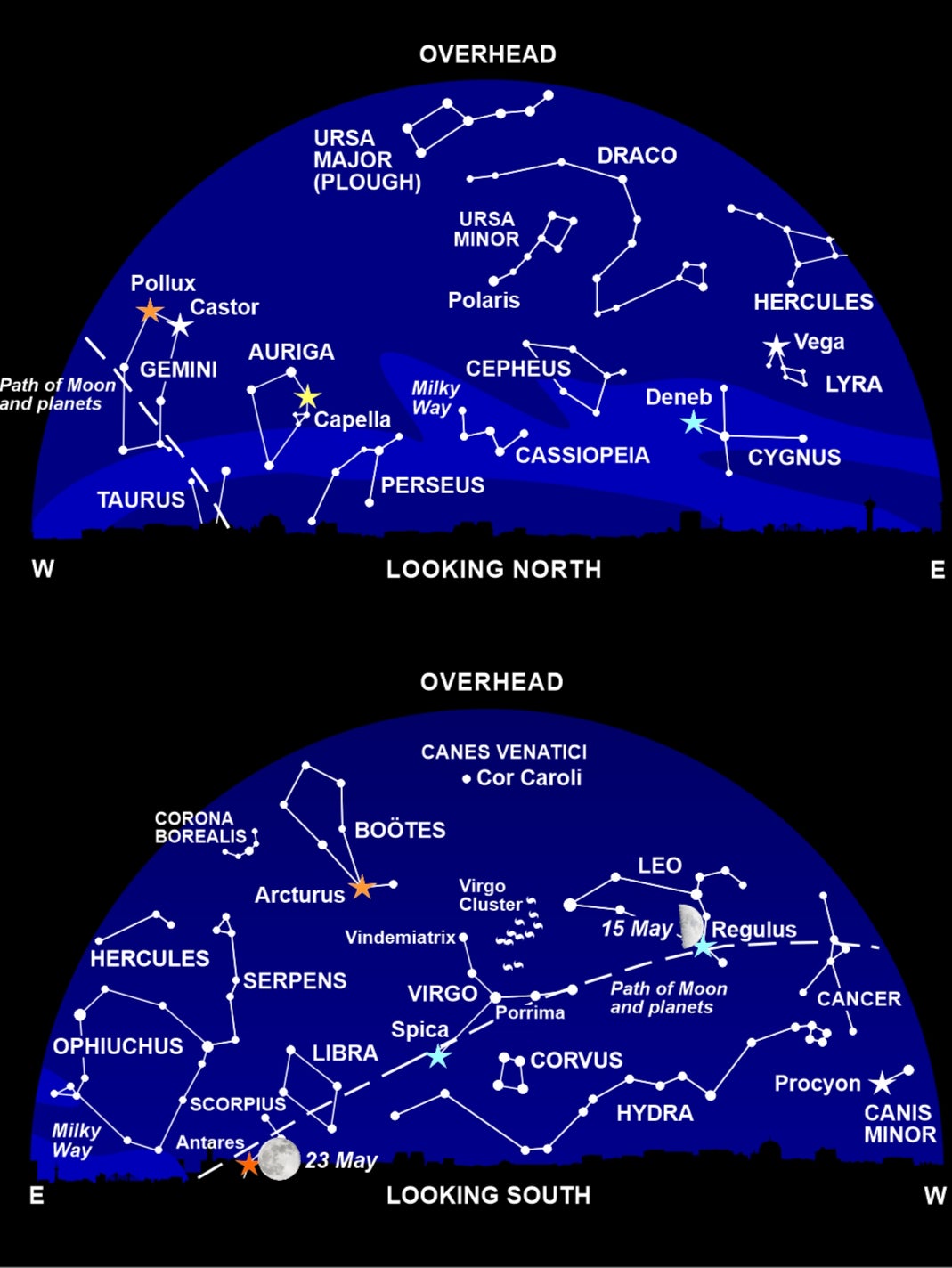

Overhead, you’ll find the familiar shape of the Plough – the seven most prominent stars of the constellation of Ursa Major, the Great Bear.

To the ancient Greeks, the four stars forming a rectangle depicted the ursine body, with three stars marking her tail. Across the Atlantic, these seven stars are seen as the Big Dipper, while schoolkids often nickname it ‘the Saucepan.’

Below the Plough crouches the cat-shaped constellation of Leo (the Lion). Follow the curve of the Great Bear’s tail (the ‘handle’ of the Plough) and you’ll find orange Arcturus, the leading light in Boötes (the Herdsman), and – further on – the brightest star in Virgo, blue-white Spica (see main story).

When the Moon becomes Full, on the night of 23 to 24 May, it just grazes past the red giant star Antares, a lovely sight low on the southern horizon.

To view any of the planets this month, we must wait up until 3am, when Saturn rises in the east, followed an hour later by the Red Planet, Mars.

Diary

9 May: Mercury at greatest elongation west

12 May: Moon near Castor and Pollux

15 May, 12.48pm: First Quarter Moon near Regulus

19 May: Moon near Spica

20 May: Moon near Spica

23 May, 2.53pm: Full Moon very near Antares

30 May, 6.13pm: Last Quarter Moon

Nigel Henbest’s latest book, ‘Stargazing 2024’ (Philip’s £6.99) is your monthly guide to everything that’s happening in the night sky this year

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments